1. Is documenta now too big to fail? In some sense this is undeniable: given the tremendous amount of financial and cultural capital at stake, it’s almost inevitable that the exhibition will manage to muster a sufficient number of respectable artworks, regardless of how persuasive its curatorial framing might be. Ever since documenta cemented its position as the most critically esteemed exhibition of global contemporary art—one might attribute this achievement to the tenth and eleventh editions, staged in 1997 (by Catherine David) and 2002 (by Okwui Enwezor)—its levels of conception and execution have been consistently above average. Whether or not one shares the sensibility of a given artistic director, few people would argue that any of the last five events have been outright disasters. The obvious, hackneyed comparison would be with a German luxury car; you might not especially like a particular model of BMW, but you know quality control won’t be an issue.

With that said, it increasingly seems that documenta has grown too big to really succeed. The problem is not just that some people love to hate a winner; or that social media has made everyone a critic, rendering critical “consensus” impossible; or that the exhibition’s influence has spawned countless imitations, thereby making it seem unoriginal. It’s also become an issue of scale: not only the ever-lengthening roster of platforms and venues and artists and publications and archives and events and broadcasts and and and… but also the epoch-defining ambition of the curatorial arguments.

In addition to the already-impossible mission of somehow reconciling all the contradictions of contemporaneity, the most recent artistic directors have tasked the show with addressing massive, fiendishly complex topics: aesthetics and politics (David), post-colonial globality (Enwezor), formalism and historicity (Roger Buergel and Ruth Noack), alternative ontologies (Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev). There simply isn’t a stable position from which any one person could capably evaluate all this material and render a meaningful judgment of it.

In many ways the current edition, supervised by Adam Szymczyk, continues this trend. Its title-slogan, “Learning From Athens,” neatly encapsulates the show’s formidable aspiration: to enable productive, educational dialogue about various forms of injustice and inequality, incorporating these concerns into its very form by sharing its contents between sites in Germany and Greece. Given the ever-hardening cynicism of the contemporary art world, it was hardly a shock when this brazenly idealistic venture began to attract wide-ranging criticism, much of which came before the second installment in Kassel had even properly opened.

What is surprising is that those responsible for documenta 14 appear to have anticipated many of these problems and proceeded anyway without too much hesitation. Perhaps the most distinctive thing about this edition of the exhibition is that it doesn’t seem to be overly concerned with how it will be reviewed or how it might go down in history. It doesn’t conspicuously want to succeed or compete or impress; what it really wants to do is engage.

Although a laudable amount of work, thought, and care have clearly gone into the show’s production, it is rarely precious or monumental or “thirsty.” To the contrary, in moments it gives off an almost scrappy, risk-taking vibe that is almost unheard of for an exhibition of this magnitude and visibility. It doesn’t aim to seduce or entertain or surround its audience. There aren’t many obvious things to hashtag or Instagram. To use one of the curators’ favorite keywords, the show invites us to “unlearn” much of what we expect from a contemporary art exhibition.

If nothing else, this documenta—to speak of the exhibition as some kind of collective subject composed of all those who made it possible—indisputably has the courage of its convictions. It exudes compassion, thoughtfulness, and gravitas with a degree of commitment that is all too unusual, whether inside or outside the sphere of art. To insist on this is not to charge the show with moralism, as many have done, but neither is it to somehow excuse it from criticism on account of its good faith: no one should need to be reminded that having the right politics (whatever that might mean) does not magically guarantee aesthetic integrity.

Rather, the point is that Szymczyk and his collaborators have challenged us in ways that deserve careful, critical, and sustained consideration. If their project is both didactic and utopian—and it undeniably, unapologetically is—its wager is that such oft-maligned qualities might yet retain some sort of value. To put it plainly: Szymczyk and his team want us to believe that art can help us learn how to work together for social justice, but only if we set aside our preconceptions. One’s opinion of the show is thus likely to turn on how one regards such an approach: Is it perceptive, promising, and admirably earnest? Or is it quixotic and naive, as some have charged—the sort of condescending do-gooderism that not only reflects inequality but reinforces it?

2. In foregrounding the entanglement of art and the aesthetic with pedagogy, ethics, and politics, the curatorial agenda of the documenta is situated comfortably within the by now well-established parameters of progressive cultural practice. Although within contemporary art discourse such concerns are typically associated with the critical program of Jacques Rancière, in a German context they are also inevitably viewed through the lens of early Romantic philosophy, most paradigmatically the work of Friedrich Schiller. Breaking with the emergent field of philosophical aesthetics, Schiller argued that art was not just the object of individual taste, but must be considered in relation to what he called “aesthetic education” as part of a larger program that would reconcile sensation and rationality in the service of collective freedom, thereby redeeming the tragically squandered potential of the French Revolution.

It is an interesting and seldom-noted irony that one of the markers that most readily identifies current art as “contemporary” or “global” is its adherence to a set of principles that remain in many ways unchanged since they were first formulated over two centuries ago, concurrently with the emergence of Western modernity. Yet while the objectives of documenta 14 are consistent with such values, they are also indebted to the more recent history of anti-imperial and anti-colonial struggle, particularly the precedents of the Subaltern Studies Group and the Third Worldist vision articulated by Frantz Fanon in his highly influential later writing.

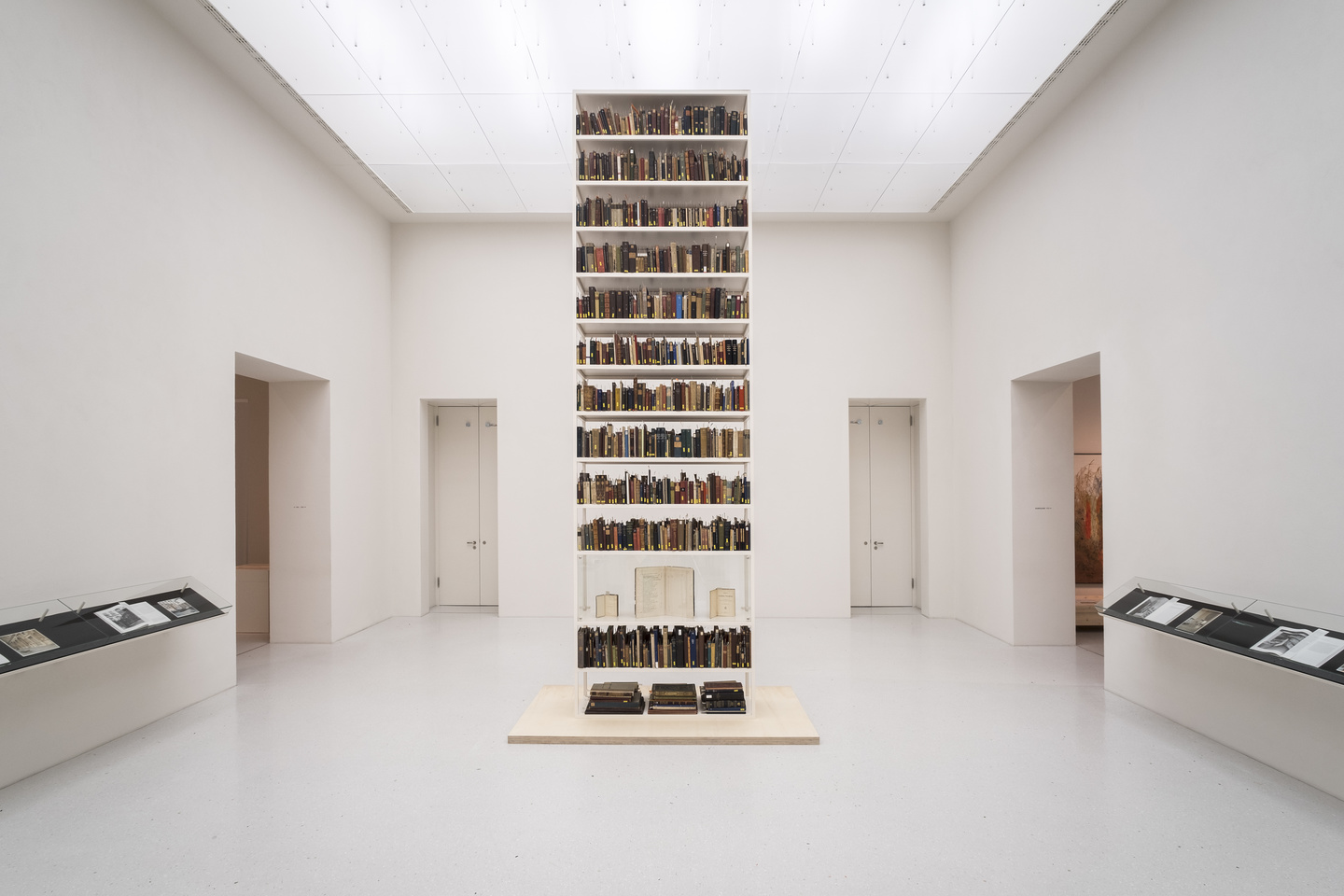

That is to say, “the global” is not framed ideologically as the horizon of Western cosmopolitanism, or as a frictionless post-historical space of total connectivity, but as a complex, dispersed site of asymmetric contestation.[1] This position was clearly signalled in a prominently placed installation by Rasheed Araeen housing the entire print run of Third Text, the influential journal Araeen founded in 1987, without which it is fair to say that exhibitions like the current documenta simply would not exist. Such displays quietly but unmistakably sought to alter prevailing art-historical consensus by conferring a kind of belated recognition to pivotal but all too frequently marginalized figures from outside global centers.

The curatorial leitmotif of “unlearning” is another point of contact with critical postcolonial theory, making an explicit link to the decolonial discourse recently popularized by figures like Walter Mignolo.[2] If decolonization entails the self-reflexive critique of the colonial relations that continue to structure epistemology, Szymczyk and his team effectively propose that art can occasion analogous effects on the level of perception and representation.

Taking things further, they frame documenta as a venue within which other forms of past injustice besides colonialism might be not just documented, but even somehow remediated. Although such an approach would be basically unthinkable in countries like the US—where neither slavery nor the genocide and expropriation of American Indians have been effectively integrated into national historical narratives—it is perfectly at home in Germany, where the practice of Vergangenheitsbewältigung (“coming to terms with the past”) has become a kind of civic religion since its conflicted origins in the early post-Nazi era.

Sidestepping predictable but unignorable objections—namely, that such an agenda asks far too much of art as such, let alone of a single exhibition—this documenta then proceeds to up the ante by engaging a similarly vast array of injustices in the present. These include economic inequality, ecological crisis, identity-based discrimination, migration, and collective violence (this is only a partial and schematic list).

Not every work in the show is explicitly topical, but the overwhelming majority are. It certainly seems that one of the chief principles guiding curatorial decisions was a concern for social justice, albeit in a radically expansive sense. At many points in the show, and in a way that strongly recalls Okwui Enwezor’s precedent, it feels as if the documenta means to serve as the world’s memory, its witness, and its conscience, even as it gestures hopefully toward some kind of nascent transnational left culture.

3. This sweeping program poses any number of challenges for those who wish to critically evaluate the documenta. The most obvious of these is practical: building on recent precedents (David’s groundbreaking discursive program, Enwezor’s series of research-based “platforms” located outside Germany, Roger Buergel and Ruth Noack’s magazine project, Christov-Bakargiev’s 100 Notes commissions), the curatorial team comprehensively decentered the exhibition by distributing it between two cities (Kassel and Athens), each of which featured numerous off-site venues, and also by expanding it to encompass cinema, performance, and theoretical discourse (hosted over the last two years by the Athens-based journal South as a State of Mind).

Under the supervision of the writer and theorist Paul B. Preciado, a series of public educational programs was presented under the rubric of “The Parliament of Bodies,” a concept meant to hybridize emergent forms of queer anarchist micropolitics with histories of radical democratic activism. In addition to various didactic or para-academic presentations, the Parliament hosted 34 “Exercises of Freedom” in Athens’ Parko Eleftherias, as well as six Open Form Societies, aesthetico-political collaborations modeled on 18th-century French abolitionist groups.

Such radical surfeit presents what is by now a familiar, unsolvable problem, namely that no one person can hope to access even half of these materials.[3] Although many have become inured to this overload, given its regularity, it nevertheless represents something like a biennial sublime, a condition that is liable to leave many viewers feeling awed, overwhelmed, or just fatigued—clearly, none of these feelings aligns with the curatorial objective of educating or mobilizing the audience.

It doesn’t help matters that in many ways this is one exhibition in two sections, one of which many viewers will never see. The curators and artists have created various interesting through-lines between the shows, but these are lost on much of the audience. While the Athens and Kassel legs each stand on their own, this documenta is clearly meant to be a whole that is more than the sum of its parts. Sadly, however, it would seem that the opposite has proven to be the case, at least for that large number of viewers who might have welcomed this multi-part experience but simply couldn’t afford it.

In one sense, the wealth of such exhibitions might be thought of as an embarrassment of riches, from which viewers are free to pick and choose according to their interests. But in another, this routinized excess is of a piece with the systemic overproduction that structures the economy of contemporary art, and which looks to many observers like part of a boom-bust cycle. Against this backdrop, some of the more salient works in the show were those that came closest to erasing themselves: Postcommodity’s Blind/Curtain, a nearly imperceptible recording of pink noise installed inconspicuously above a revolving door at the threshold of the Neue Galerie; or Pope.L’s Whispering Campaign, a series of barely decipherable, borderline inaudible messages played from hidden speakers, paired with surreptitious street performances at unannounced locations.[4]

Another issue is the fact that much of the art in the documenta can’t be so easily mapped onto the coordinates used by many critics. While the curators have largely eschewed an explicitly anti-capitalist position, there is nonetheless a notable lack of blue-chip, market-proven artists with major gallery representation. Paintings and sculptures are present, but not privileged; there is a fair amount of media art, but nothing conspicuously post-internet or dependent on headsets or other gizmos. Even though much of the work in the show is readily legible as “biennial art,” relatively few of the artists selected are well-established on the circuit of major biennials. This in itself is no small accomplishment.

At a time when major art fairs are increasingly fashioning themselves after biennials by incorporating public programs and mini-exhibitions of trending styles, it is hard to think of a single way in which this documenta resembles Art Basel or Frieze. There is very little irony or fashion or exuberance or humor or sex. There are scarcely any pieces that indulge the aesthetics of spectacle, or that aim primarily to entertain or to provide sensory pleasure. This means that much of the art is likely to be dismissed as overly “difficult,” in that it makes explicit demands of the viewer while putting considerable pressure on conventional definitions of contemporary art, if not simply ignoring them altogether.

A prominent, excellent example of this attitude is Forensic Architecture’s 77sqm_9:26min, which presents the results of an investigation into the unsolved murder of a Turkish youth in Kassel. In a somewhat clinical but utterly riveting video, a narrator methodically reviews various forms of evidence, explaining how a research team used audio analysis and digital modeling to disprove the alibi of a state secret service officer who was at the scene but not convicted.

Many of us have come to expect the unexpected from art, but even so it comes as a chilling shock to be led through this convincing demonstration that this policeman was the only suspect who could have committed the murder. Under such circumstances, art is a source of funding and public exposure but apart from that basically an afterthought. It seems doubtful that members of the team genuinely care whether viewers regard their work as video art or as documentary or as activism; they are focused, admirably, almost exclusively on securing justice. One could say such work is not medium-specific, but medium-agnostic; what matters most is not how it is made but that it is made and that it then makes things happen.

There is to be sure plenty of Art-art in the show, some of it quite interesting and not at all well known. But there is just as much art that wishes to negate or transcend the autonomy of art, or art that seems indifferent to its own status as art, or historical artifacts that are framed as “art” even though they were produced for entirely different purposes. Without calling undue attention to this strategy, the curators effectively deprivilege the still-hegemonic modern Western bourgeois conception of art by showing its historical contingency, revealing its constitutive contradictions, and juxtaposing it with historically and culturally divergent models of the aesthetic. It is an open question how well this approach will be able to engage different audiences. Those without much exposure to this approach might be put off by how much prior knowledge is assumed and how much intellectual work they are asked to do; purists could deem the show guilty of a vapid pluralism; some frequent biennial-goers are likely to think that many of its themes are unoriginal.

What seems clear, however, is that this documenta raises a range of questions that aren’t answered easily, if at all, particularly when one factors in the broad array of extra-artistic materials that are also part of the exhibition. How should we respond to works that combine aesthetic and ethical appeals, or that occupy the sphere of art while foregrounding their own desire for political change? What is lost when art produced under conditions of duress, sometimes as a means of self-preservation, is presented alongside art made for art’s sake? In what ways might aesthetic contradictions begin to serve a political function, assuming they even can? And is it possible to reconcile the documenta’s avowedly leftist commitments with its role in the cultural politics of the German state?

4. Much of the mainstream critical response to the Kassel show has tended to ignore such questions, instead racing to deliver snap judgments, incite controversy, or peddle cynicism, all of which are of course the quickest route to click-throughs and eyeballs. Though such responses usually say more about the prevailing media ecology than they do about the show, they also read as a backlash against the particularly uncompromising attitude of the current documenta. Unlike some of their cagier peers and predecessors, the curators of this edition haven’t sugared the pill by punctuating the prevailing tone of sobriety with moments of escapism or indulgent sensuousness. Many critics found it irresistible to reframe such seriousness of purpose as a kind of po-faced, priestly moral superiority; one prominent review in the widely-read weekly Die Zeit was entitled “In the Temple of Self-Righteousness.”[5]

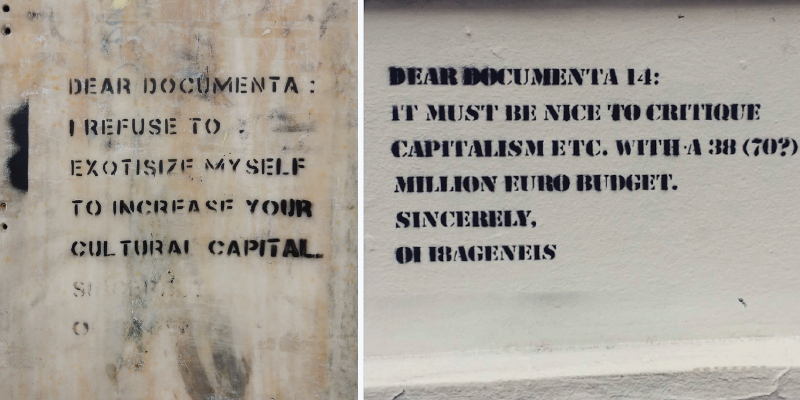

While the tone and contents of such reviews have varied, they tend to express similar grievances: this documenta is excessively political; this documenta is politically correct; this documenta is the return of 1990s identity politics; this documenta fetishizes the Other. Taking documenta as a synecdoche for Western European privilege, much of this criticism essentially argued that the exhibition was the product of ignorance, fantasy, or bad faith. On this view, the show is ultimately not about the art or the artists, but about the collective performance of something like a white savior complex. Gestures that might appear to be altruistic are in fact deeply narcissistic and manipulative, in that their apparent concern for the suffering of others is actually only a means to exorcise Europeans’ own guilt.

Turning that logic against itself, one could just as easily say that such criticism makes little effort to engage the concrete particularity of an exhibition’s argument. Instead, it empowers the critic to perform a dramatic act of unmasking, as in the climax of a detective novel, providing readers with the added jouissance of seeing a bunch of holier-than-thou art snobs brought down to size. Although such claims approximate the received idea of “criticality,” they are belied by any close examination of the actual art in the show, not to mention the simple fact that the documenta’s curatorial team was in fact markedly diverse, decentralized, and highly critical of its own place within the power dynamics of European institutions. It could well be that the strongly defensive character of these criticisms has more to do with privileged Europeans’ own sense of shame—which is doubtless exacerbated in a moment of resurgent nationalism and ethnocentrism—than it does with any attempt to turn the documenta into some kind of inquisition.

Yet while such arguments essentially misinterpret the rhetoric of the exhibition, detecting partisan accusation where there is none, they are nonetheless right in sensing that questions of responsibility and justice are at the very center of the show. Such commitments clearly informed the decision to expand to Athens; whether or not this move was in essence neocolonial, as many claimed, it undeniably marked an effort to offset the punitive austerity measures forced on Greece by the EU, spearheaded by German politicians in the interest of their nation’s overextended banking industry.

A similar concern for accountability was behind Szymczyk’s inspired but ultimately unsuccessful effort to devote Kassel’s Neue Galerie to exhibiting the entire Gurlitt collection: the massive hoard of artworks discovered in 2012 in the apartment of a Munich pensioner whose father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, was a leading dealer of expropriated art under the Nazi regime. Without denying the striking impact such a display might have had, it is still worth questioning what exactly it might have accomplished. There is little need to raise public awareness of this episode, as anyone who visits documenta in Kassel is almost certain to know about the Gurlitt works and their history, especially if they are German. If anything, such a display might have suggested that the German state was being fully transparent and cooperative in working to restore these objects to their rightful owners, a view that many would dispute given its delayed responses and the fact that only five of the 1500+ works have so far been returned.[6]

Even though this plan failed to materialize, its spirit lives on in the Neue Galerie, particularly in a group of rooms on the museum’s second floor that effectively functions as the “brain” of this edition, telegraphing its argument about the relations between art, politics, and history. The key moment of this sequence is Maria Eichhorn’s Rose Valland Institute, a suite of works devoted to the history and legacy of Nazi expropriation. Drawing on the pivotal precedent of Hans Haacke’s Manet-PROJEKT ’74 (1974), Eichhorn used an open call to research and document the systematic looting of Jewish-owned property, not only across Germany (including in Kassel) but also in Nazi-occupied France.

Although the project takes a broad range of forms—these include a research workshop, displays of looted works, a reading room, video projections of official memoranda, and a towering shelf of Jewish-owned books that had until recently been in the collection of a Berlin state library—its distinguishing characteristic is its balance between rigorous determination and painstaking care. Despite the relative familiarity of the topic, not to mention Eichhorn’s reputation as a clinical, cerebral artist, the end result is quietly overpowering.

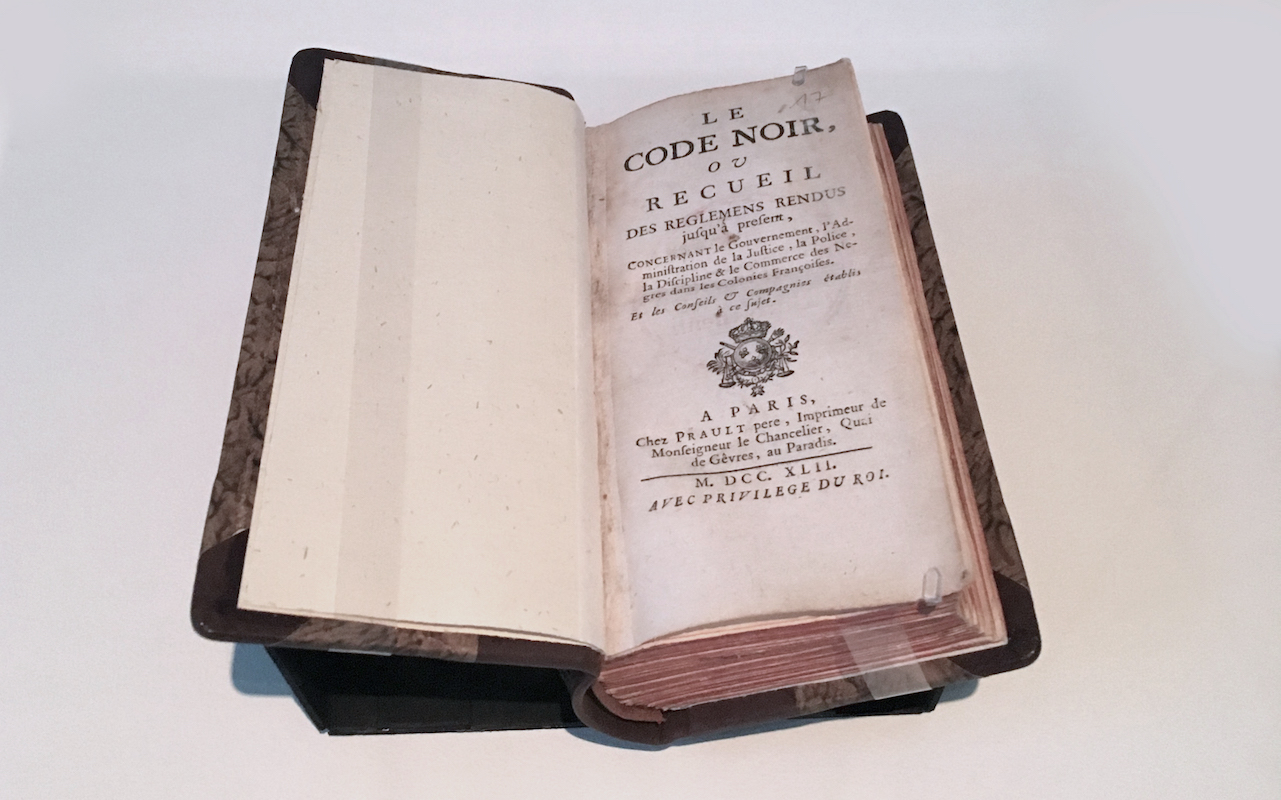

Taking this approach as a model, the remaining galleries on the floor are devoted to other instances of historical injustice. Upon exiting Eichhorn’s mini-exhibition, viewers encounter a series of works pertaining to the European colonization of Africa: an installation by Sammy Baloji questioning the museumization of Congolese artifacts (Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues); materials from a pedagogical experiment run by Pélagie Gbagduidi (The Missing Link. Dicolonisation Education by Mrs Smiling Stone); and a copy of the Code Noir, the infamous 1685 document which codified French imperial policies pertaining to native African populations. The analogy between these different modes of domination was unmistakably clear, not seeming to register the fact that many historians would find such comparisons troubling.

Other rooms in the Neue Galerie are dedicated to similarly weighty topics, including the transatlantic slave trade, the Bengal Famine of the 1940s, and the role of agronomy in the modernization and liberation of colonized nations. Rather than hold these events at a safe archival distance, such displays aimed to draw explicit parallels with the present, whether through references in wall texts or by juxtaposition with objects currently in museum collections.

Passing through this vivid, somber panorama, one couldn’t help but recall Walter Benjamin’s famous thesis that every document of civilization is inevitably also a document of barbarism. In its more elegiac moments, the exhibition also brought to mind Benjamin’s early work on Baroque Trauerspiel, with its saturnine vision of human history as a kind of mourning-play. At such points, to “learn from Athens” came to signify a similarly dark narrative, in which the development of Western civilization is staged as a kind of meta-historical tragedy.

5. There are moments when the exhibition resembles some sort of requiem for the countless victims of history. It is very powerful to be beside oneself with grief or sympathy for people one never knew and can only begin to imagine. It is also highly problematic, in part because such affect encourages (or even depends on) a fundamental misidentification, but also because it is so easy to get wrong, lapsing into mawkishness or bathos.

Thanks to the sound judgment of its curators, this documenta largely avoids such pitfalls by consistently presenting a more nuanced picture. Even as the exhibition powerfully affirms the ability of art to represent all manner of injustices, it also problematizes this function by gesturing toward the compromises and contradictions that structure the public life of art. No matter how pure an artist’s intentions may be, art is inevitably produced, distributed, and received under contaminated conditions; it simply cannot be divorced from power and therefore from inequality, if not exploitation.

To its substantial credit, and in what is likely a first for the documenta as an institution, the current edition does its best to address this problem head-on and from a thoroughly immanent position that doesn’t exempt itself or proclaim a false reconciliation. In much the same way that Eichhorn shows how Nazi policies continue to determine the use of objects and the functioning of institutions, Szymczyk’s team has sought to show how specific histories of domination still resonate within the exhibition they themselves have curated.

This attempt at a kind of auto-institutional-critique is clearest in a series of displays that chronicle modern Germany’s idealization of classical Greece, a fantasy that was realized not just in travellers’ landscapes or the expropriation of artifacts, but in the emergence of aesthetics (and later art history), the development of post-Kantian philosophy, the propagation of nationalist discourse, and the visual culture of Nazism. Although this history is far too complex and important to function as a minor theme, as it does here—it should really have its own exhibition in a major German museum—it was nevertheless interesting to see explicit connections drawn to the post-1945 era. By including classically themed drawings by Arnold Bode, who essentially founded documenta, organizing the first four editions, the curators cleverly paid tribute to their predecessor even as they subtly questioned the thinking behind his exhibition, which functioned as ideology in numerous ways.[7]

In such instances, art occupies the intersection between individual experience and larger, transpersonal conditions. Variations on this theme are threaded throughout the Kassel show like a leitmotif: art as a refuge from oppression; art as a means of resistance; art as a way to mobilize solidarity; art as a response to crisis; art as an adaptation to adversity. While it is not particularly innovative to frame art as essentially a survival mechanism—such rhetoric has been a staple of biennial discourse for some time—audiences in the global North often need to be reminded that the bourgeois liberal-democratic autonomy of art is by no means universal.

Of course, none of these ideas would matter if they were used to excuse bad art, or if they were forced down viewers’ throats. Fortunately, there are many places where the opposite is the case. Nearly half of the work in this documenta was produced by artists who are now deceased, many of them relatively unknown to a contemporary art audience. One of the more rewarding aspects of the show is its rehabilitation of such work, which is typically presented in an intelligent but modest fashion: not as a historicist fetish, but as part of an attempt to subtly but firmly controvert the presentism of much contemporary art discourse.

Any number of examples spring to mind; there may in fact be as many memorable historical works as new commissions. For this writer, some of the most compelling are the following: ingenious typewritten poem-drawings and minimalist mail art by the East German Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt; Algirdas Seskus’s lambent, tender, elegiac photographs of everyday life in Soviet Lithuania; books, performance ephemera, and conceptual moving image work produced by the Mexican polymath Ulises Carrión; and the visionary autodidactic cosmology of Valery Pavlovich Lamakh. I have long enjoyed the drawings and fables of Bruno Schulz, but I was utterly unprepared (and quite moved) to come across a suite of recently rediscovered fresco paintings he had made at the bequest of an SS officer while imprisoned in a Ukrainian ghetto, not long before his death in captivity.

As elsewhere, such displays produce genuine pathos, even if they flirt with the fantasy that curatorial diligence (or enlightened spectatorship) could somehow magically redeem the dead by dignifying their suffering or posthumously making them into art-martyrs. This risk increases the more that one learns and starts to sympathize with the artist. Some of the most powerful works in Kassel fall into this category: these include works on paper by Cornelia Gurlitt, the sister of Hildebrand, who took her own life following her service as a nurse during World War I; the grotesque, beguiling tumors sculpted by Alina Szapocznikow during her battle with breast cancer; and the striking output of Lorenza Böttner, a transgender double amputee who combined mouth and foot paintings with public performance. In such cases, it isn’t clear how to distinguish aesthetic claims from ethical or political ones; neither is it evident whether such distinctions are relevant or even possible in this context, and also what it might mean to do without them.

6. Against this historical backdrop, the selection of recent and commissioned artworks subtly begin to assume a different focus. Instead of the default grammar of the contemporary biennial—loosely thematic, superficially topical, often rather arbitrary groupings dictated as much by contingency or curatorial fashion as by clearly defined criteria—documenta 14 grounds itself in an argument that is implicit but insistent, and which might be paraphrased as follows: given its entanglement with histories of domination and privation, as well as with the pervasive inequalities that characterize the current global crisis, contemporary art and its institutions must commit themselves to the remediation of injustice using whatever means they can mobilize.

Is such thinking a creative call for ethical vigilance, or is it essentially an elaborate highbrow guilt trip? This question, possibly more than any other, is likely to determine whether someone leaves Kassel voicing defensive recriminations or whether they leave with some mixture of ambivalence, exhilaration, concern, and gratitude.

To say that such responses are a matter of taste, and therefore somehow moot, is an easy way to dodge the very difficult question of how one’s own judgment is sociopolitically conditioned. In other words, someone’s support for this documenta will likely have little to do with their disinterested evaluations of artistic form, but rather will probably depend largely on things like their willingness to regard the suffering of others, or their level of comfort with their own privilege, or their readiness to disregard established ideas about what art is or how it operates.

The obvious reason that some critics have cast Szymczyk and his team as morally superior “social justice warriors” is that it is much easier to fling stereotypes than it is to work through the complex implications of the fundamental message that this documenta means to communicate. At the core of this sprawling, wildly ambitious, sometimes incoherent, but certainly worthwhile exhibition lies a deceptively simple proposition: that art can and should serve the cause of justice, but not always in the ways we might expect.

The show’s detractors are entirely right that it makes strong ethical demands of its audience; what they miss is that this open, uncompromising appeal is coupled with a healthy respect for the self-determination of artists and their audiences, as well as for the peculiar agency of art itself. The curators haven’t acted as revolutionaries or propagandists, but rather in a more horizontal, experimental, and collaborative or catalytic mode. Like Hegel’s “vanishing mediator,” they have sought to do their work (in this case by providing artists, many of them relatively underexposed, with resources and a platform) before discreetly stepping aside.

7. Some of the most memorable contemporary works in Kassel are those that initiated new forms of contact between ethics, politics, and aesthetics, encouraging viewers to question the relations between these spheres. For a project with the provocative title Heimat (2016-17)—the term, which connotes something like “homeland,” played a central role in the National Socialist imaginary—the Palestinian artist Ahlam Shibli has researched and documented two migrant populations living in the area around Kassel. One consists of so-called Gastarbeiter (“guest workers”), many of whom first came from various Mediterranean states to West Germany in the post-war decades to shore up the country’s decimated labor force; the other comprises the ethnic German Aussiedler who had emigrated to Nazi-occupied territory in Eastern Europe but were forcibly repatriated after Hitler’s defeat.

Although the form of Shibli’s installation initially seems rather conventional—series of framed images and texts, hung in grids like much documentary or conceptual photography—it soon becomes clear that she has subtly arranged the groupings such that some of them represent specific communities or places, while others are intermixed. Having clearly gained the trust of her different subjects, Shibli has solicited testimonials that powerfully register the complexity of highly sensitive topics, such as the recent resurgence of neo-Nazi violence in the vicinity of Kassel, or the tendencies toward self-victimization and self-exculpation in German vernacular memory.

This utterly arresting material doesn’t just provide insight into the history of interethnic contacts in the region; it also juxtaposes these entangled narratives in a way that resists the temptation to debate the severity or moral equivalence of different traumas. Although the piece makes no direct allusions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the unmistakable shadow of that history lends an added degree of poignancy, especially when considered alongside the body of work Shibli showed in Athens, which explicitly addressed the occupation.

In its patient, attentive construction of a decades-long genealogy of migration, Heimat responds to the EU’s ongoing refugee crisis in a way that favors obliquity and granular detail over sensationalism or emotional button-pushing. Similar techniques are used in another outstanding work, Bouchra Khalili’s The Tempest Society, which builds on the artist’s longstanding engagement with migrant populations and non-professional performers to poetically illuminate the ties linking emigrant with homeland, actor with chorus, and citizen with polis.

Such approaches are ultimately more productive than the comparatively direct route taken by some other works in Kassel. Although thankfully the show includes nothing like the sort of high-budget, low-concept emergency Pop one now associates above all with Ai Weiwei, it does prominently feature a number of refugee-themed installations, none of which is entirely successful. In a piece that was awarded this edition’s Arnold Bode Prize, Monument for Strangers and Refugees, Olu Oguibe has erected a massive obelisk on a central plaza, upon which is inscribed a biblical verse about hospitality in German, English, Arabic, and Turkish; the benevolent cosmopolitanism of this gesture is uncomfortably at odds with its grandiosity and its invocation of Christian charity.

As part of a similarly monumental work entitled Fluchtzieleuropahavarieschallkörper (“refugee-destination-Europe-accident-soundbox”) Guillermo Galindo has built a room-sized instrument out of flotsam scavenged from Mediterranean beaches. Apart from its occasional use to perform compositions by the artist, the piece exists mainly as an overly literal, rather sentimental memorial that can’t really begin to engage the question of how (or even whether) this particular audience might be able to mourn the ever-increasing number of migration-related deaths.

The Kurdish-Iraqi artist Hiwa K has recently been attracting fast-growing and well-deserved interest, thanks to an absolutely stellar solo show at KW in Berlin and a strong contribution to the Athens installment of the documenta. He has received considerable media attention in Kassel; this is surely because of his personal story (he is one of the few artists in the contemporary art world with actual experience as a refugee), but also reflects the Insta-genic popularity of his large, prominently located public sculpture When We Were Exhaling Images.

The piece is a 4×5 stack of huge pipes of the sort used to build water mains; these contain model living spaces for refugees, which look a bit like entries in a socially conscious architecture competition sponsored by IKEA. The joke is that none of the spaces are livable, given their inhuman dimensions and warped, funhouse design. As a satire of the insufficiency of the EU’s response to the migration crisis, it’s brilliant (at the official opening in Kassel, the artist invited the German President to enter one of the spaces; this invitation was politely declined). However, one misses the soulfulness and poetic melancholy that give the artist’s other work such depth, and which give his sardonic wit something to push back against.

If the refugee emergency is one prominent through-line, environmental disaster is another. (Given the multi-year gestation of the commission process, there were few references to the right populism and neo-fascisms of the Brexit/Trump era.) Perhaps because of the strongly ecological tenor of the previous documenta, this problem is treated less prominently and somewhat more inconsistently.

One of the better works in the show, Angela Melitopoulos’s video installation Crossings (2017), uses extensive on-site research in Greece to weave together speculative reflections on water scarcity, refugee camps, collective praxis, and the politics of geography; her deft use of multiple video and audio channels remaps these considerations onto the viewer’s perceptual space to compelling effect. One of the most laughable is the work of the American activists Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens, who are leading bemused visitors on “ecosexual” walking tours; what might have been meant as a campy avowal of tree-hugging environmentalism falls utterly flat, coming off as the most galling kind of Californian hippy-dippy naiveté.

8. Such thematics are entirely consistent with the sort of zeitgeist-capturing emergency-response model to biennial curation that is typically associated with Okwui Enwezor’s documenta, and which has basically been conventionalized in the fifteen years since. The relative ubiquity of the style is not in itself a problem; in a world that seems to be speeding ever more manically into the abyss, one welcomes any effort to make people care. Neither is it necessarily true that crisis-curating automatically numbs viewers to outrage, as some might allege.

Rather, the issue is that such an approach threatens to reify the very terms it depends on, above all “global” and “contemporary.” The ideal of the global village is at this point inseparable from the reality of the globalizing neoliberal market, whereas interest in contemporaneity lends itself all too easily to a kind of shallow presentism, or else to the trend-chasing of fashion and other “creative industries.” As concepts, the global and the contemporary typically function as false universals; one doubts the emergent notion of “the global contemporary” will be any different.

One easily overlooked but important achievement of documenta 14 is that it begins to chart a potential route out of this impasse by exploring ways to double back against the rhetoric of global contemporary crisis. Some of the most generative moments in the show occur when it provides glimpses of alternative local or regional histories that diffract the apparent unity of the present, revealing it to be something other than what we think we know. Transnational and transregional exchange outside the global North are crucial in this respect, and the Kassel show includes some riveting instances of such contact, even if one wishes it might have gone further still.

Gordon Hookey’s towering mural MURRILAND! is a prime example; inspired by the Congolese painter Tshibumba Kanda Matulu (whose work is on view in Athens, but not Kassel), Hookey has drawn on oral histories of various Aboriginal communities (including his own) to elaborate a polemical counter-history of Australian settler colonialism. Lala Rukh’s work is another: during the 1980s and 90s Rukh was an active advocate for transnational feminism in South Asia and the global South more broadly, and the display of her work in the Documenta Halle raises fascinating questions by exhibiting forceful political posters alongside her highly abstract, darkly lustrous graphite drawings.

The problem of left transnationalism receives its most rigorous and productive treatment in a terrific piece by Naeem Mohaiemen, whose contribution in Athens was a spare yet devastating feature-length video shot at that city’s abandoned Ellinikon airport, in which a cancelled flight occasions elliptical, tragicomic, and intensely absorbing meditations on historicity, geography, neoliberalization, postcoloniality, and finitude.

His piece for Kassel, an equally memorable multi-channel video installation entitled Two Meetings and a Funeral, examines the crisis of the Non-Aligned Movement through archival research, interviews, and an associative montage of internationalist architecture in New York, Algiers, and Dhaka. As much as the work recalls Chris Marker’s A Grin Without A Cat (1977), whether in its essayistic rigor or its left-eschatological orientation, it shows remarkable composure in defining its own ambitious objectives, particularly by taking a step outside the default secularism of most leftist thought.

If these two markedly distinct yet subtly interrelated works speak to the scope of Mohaiemen’s capabilities, they also function as a kind of keystone for documenta 14: beyond linking the exhibition to the crucial precedent of transnational left movements, particularly the cultures of Tricontinentalism, they venture to address the profound contradictions that constrained and ultimately destroyed these models of solidarity, leaving a deeply divided legacy for those who might wish to reclaim their history.

9. None of this is to say that the exhibition is perfectly consistent, or that all its gambles pay off, or that it’s not at times weirdly ham-fisted. The general consensus in Kassel has been that the curators’ largest mistake was to use the Fridericianum, documenta’s ur-venue, to redisplay the collection of the Greek national contemporary art museum EMST (which would otherwise have been in storage during the Athens leg of the show). Such judgments are sadly confirmed soon after entering the Fridericianum, as it is quickly becomes clear that a discouraging amount of space has been devoted to minor or widely circulated pieces by excellent artists (Emily Jacir, Walid Raad), as well as predictable products from the studios of overexposed, superficially “contemporary” stars like Bill Viola.

The majority of this tepid show-within-the-show consists of work by Greek artists, few of them known outside Greece, displayed in groupings that mainly just highlight continuities with the development of modernism and postmodernism elsewhere. A good deal of this is well-executed and of genuine historical interest, but there is relatively little that challenges prevailing narratives; one notable exception is a suite of sharp mixed-media sculptures on the topic of migrant labor by the expatriate Vlassis Caniaris, which were produced in West Germany in the mid-1970s. Although there are solid contributions from such younger artists as Stefan Tsivopoulos, Haris Epaminonda, and Eirene Efstathiou, none of these gain much from being shown in this manner and would likely have been better served in another venue.

Some of the most incisive criticism of the Athens installment has homed in on the gap between its generally good intentions and their erratic realization, or its apparent disregard for the thoughts or needs of its Greek partners and audience. (In a country with more than 50% youth unemployment, the desire to learn marketable job skills surely far outweighs any interest in unlearning elite artistic conventions.) Yanis Varoufakis scored cheap points in quickly alleging that documenta’s expansion amounted to “crisis tourism”—would he really prefer that the show had simply stayed in Germany?—but he and others have been right to call out the ways in which organizers have failed to leverage their funding so as to most effectively benefit Athenian art institutions, especially independent spaces.[8]

In a similar vein, the problems with the EMST-Fridericianum venture aren’t so much about conception, but rather execution. No matter how hard the curators may try to frame this part of the show in terms of hospitality, reciprocity, and generosity (inspiring countless lame Trojan horse jokes in the process), it is impossible to bracket out the larger context of massive macroeconomic disparity between the two states involved. Cooperation is one thing, but to cast this as some sort of exchange between equals is either to perpetuate a neoliberal ideology of free trade or to willfully deny widespread German resentment of Greece as a freeloading debtor state.

There is also something uncomfortably patronizing about this gesture of recognition, as if we should all be praising the German cultural establishment for its magnanimity. Such unfortunate impressions could easily have been avoided by sharing authority equally with Greek curators, or by dispersing these works throughout the show in more considered arrangements, or even by simply including Greek translations in the wall texts and didactic materials.

A less widely noted but equally unsettling curatorial error takes place at the Ottoneum, a Baroque building which was Germany’s first theater and now serves as a natural history museum. In theory, the vision for the venue is sensible enough; the official website describes a plan to reframe the site’s history by displaying artworks that deal with what it calls “the theater of land.” In practice, one soon realizes that every selection in the show deals in some obvious way with what most European viewers would identify as Otherness: there are two Mongolian artists (Nomin Bold and Ariuntugs Tserenpil), one of whom has recorded himself eating moss; a wall of enlarged images of African mega-cities shot by the Nigerian-British photographer Akinbode Akinbiyi; and a series of projects about indigenous populations in Colombia, Australia, Cambodia, and the Sápmi region of Scandinavia, several of which were carried out by indigenous artists.[9]

One cringes to realize that these artists, each of whom fully deserves to be in the documenta, have somehow all been grouped together, as if what links them is their exoticism. To make matters much, much worse, all this happens under the rubric of natural history, conjuring up the specter of Rousseau’s noble savage and all manner of other pseudo-Darwinian monsters. The only exception is a film by Rosalind Nashashibi (Vivian’s Garden), which portrays a mother and daughter, both artists, who live in self-imposed exile in rural Guatemala; notwithstanding its tenderness and languid beauty, in this context the piece speaks more to the ways in which coloniality still haunts even the more progressive regions of the Western imaginary.

It is of course hard to imagine that any of this occurred purely by accident; it is much more likely that the selection was meant to be some sort of immanent critique of Eurocentric museology, which would hardly be innovative but would nevertheless have been welcome. The problem is that there are few if any signs to suggest such intentions, even when a trained eye looks closely for them. Absent any effective curatorial frame, the artworks are liable to engender precisely the effects they were meant to oppose.

10. Given how much the rest of the exhibition is able to accomplish, it would be unfair to dwell on the problems of the Fridericianum or the Ottoneum. No matter how surprising these are, they don’t really rate as a proper fiasco. Rather, they fall somewhere between full-on curatorial catastrophe and the smaller errors of execution that are probably inevitable for a show of this magnitude: some glaring instances of sound bleed (Alvin Lucier’s marvelous painting-instrument Sound on Paper (1985) was basically inaudible); difficulties in realizing the curators’ promises to highlight experimental music (the inclusion of score displays and a listening station were perfunctory); the much-bemoaned lack of easily understood resources to help visitors navigate between the many small venues spread across the city (why no app?).

The relevant point is not, as some would have it, that such missteps reveal a persistent tendency to fetishize difference; if anything, they stand out precisely because the work of “different” artists is generally handled scrupulously.[10] The issue is rather that both the Fridericianum and Ottoneum show how problems of Otherness remain a major problem, even in an exhibition as painstakingly mindful as this one, even after decades of attempts to decenter modern and contemporary art.

No one would mistake Learning From Athens for Jean-Hubert Martin’s now-canonical 1989 Pompidou exhibition Magiciens de la terre. Although the influence of the latter is evident in this documenta’s pan-historical globalism and its anti-ethnocentrism, there are relatively few moments where the current show cultivates fascination or exoticizes its contents. With this said, the genealogy of the documenta 14 aesthetic clearly leads back to Magiciens, as well as to the other two landmark shows of 1989, the Third Havana Biennial and Rasheed Araeen’s The Other Story. In other words, despite all its decolonial, quasi-Third-Worldist allegiances, the show can’t quite extricate itself from a more liberal 1990s establishment multiculturalism.

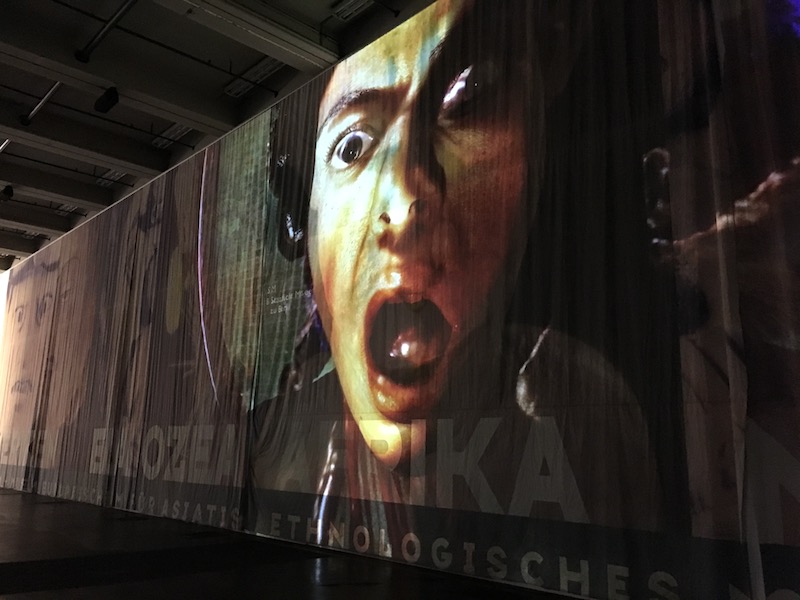

This conflict produces a certain inconsistency when it comes to the critical standpoint of the Kassel show. In some places the politics of decolonization are writ large, literally, as in Theo Eshetu’s Atlas Fractured, in which images of masks are projected onto a huge banner that was once used to advertise Berlin’s ethnographic museum. In others, viewers are presented with a much less problematic otherness, one that is gracious, non-threatening, and essentially generic or devoid of meaning insofar as it means little more than “non-Western.”

This is unfortunately the case with the presentation of El Hadji Sy’s installation Disco-Concertation (2016): without a clear link to Sy’s longstanding art-activism in Senegal, there is no way for documenta visitors to know that the primary audience for this work was actually Senegalese manual laborers; they are instead likely to interpret his colorful paintings of fishermen with well-meaning condescension as a kind of picturesque folk art.

For artists outside the global North such reception can be a kind of poisoned chalice: while it enables international success it also requires a sort of self-tokenization, in which artists conform their practices to the expectations and desires of a privileged “global” audience. Part of what is being sold in such transactions is the fantasy that North-South divisions can be resolved without real conflict, whether through cultural diplomacy or under the enlightened auspices of so-called “progressive capitalism.”

Another crucial source of value is authenticity, a term whose meaning is famously slippery but which in this case has much to do with lingering colonial fantasy, as well as with the received idea of the Southern artist as “the voice of his people,” someone who can translate local folkways into the vocabulary of modernity. In the role of an unofficial ambassador, this person is empowered to help broker the unspoken negotiations in which various forms of exploitation are essentially rationalized in the name of cultural exchange, and in which artists are essentially caught between the competing agendas of multinational corporations, aid agencies, comprador elites, and the art market.

Questions of authenticity were central to the multiculturalism discourse of the 1980s and 90s, whether in postcolonial theories of hybridity or in debates over emergent mainstream genres like World Music. As is clear from the recent spate of controversies over ethnicity and “cultural appropriation”—which have yet to hit Europe as hard as they have the US, although they seem likely to—these conflicts may have been displaced for a time but they were never really resolved (assuming such a thing is even possible).

They are clearly manifest in one of the stranger moments in Kassel, a reverential display in the Documenta Halle dedicated to the career of the great Malian guitarist Ali Farka Touré, who rode the World Music wave to global fame in the 90s, recording crossover collaborations with white American musicians like Ry Cooder. Touré’s musical merits are beyond doubt; what’s not is the reason he should be in documenta. The many visitors who already know his work will learn little of interest, whether about his lyrics or his political career; those who don’t are ill served by an installation that feels like a cross between a hipster record boutique and a Hard Rock Café. No argument is made for how anyone gains by framing Touré’s work as art in this setting.

Such cases concern more than curatorial judgment, in that they ultimately pertain to the conflicts that arise when any elite cultural institution in the North pursues a strategy of inclusion. One lesson of this documenta might be that the problems of exoticization and tokenization are more stubborn or complex than most liberal curators are prepared to deal with, as the examples above indicate. Another is that even the most well-funded exhibition can never be all-inclusive; this is made clear by the jarring, inexplicable absence of Chinese contemporary art (the only work by a living Chinese artist in Kassel was a program of films by Wang Bing). Without a clear rationale for selection, even a show as massive and comprehensive as documenta starts to feel somewhat eclectic, like an unfinished encyclopedia.

The most intractable problem, however, is that the fundamental power imbalances that are manifest in even the most well-meaning gestures of inclusion can’t simply be curated away. It seems likely, for instance, that any attempt to show indigenous art in a major Northern biennial organized by non-indigenous curators will inevitably carry a whiff of enlightened neocolonialism, as if the organizers were somehow judging the merits of different native peoples before putting them on display. Cultural authority can be decentered and distributed, but in the end there remains someone who has the power to include and someone who doesn’t. The more that inclusion is figured as an end in itself—whether by curators, artists, critics, or activists—the less possible it becomes to question or contest the concrete conditions that are responsible for exclusion in the first place.

11. While some of this documenta’s core contradictions can thus be traced back to the cultural politics of globality, others stem from problematic tendencies within the field of contemporary art. Foremost among these is the question of art’s heteronomy: its determination by factors outside art or beyond art’s control, such as the now-common expectation that art not only do something, but do something more than art is conventionally expected to do.

If one of the defining characteristics of contemporary art is its pronounced heteronomy, a prominent expression of this change is the large amount of current art that is in one way or another meant to be aboutsomething. Artists now make work that is “conscious of” or “responding to” or “informed by”—i.e., about—a virtually infinite range of subjects, even if the precise nature of this relation is rarely explained. Meanwhile, critical reception of this work is increasingly dependent on details of the artist’s biography and social context, as the recent storm of controversy over Jimmie Durham’s ethnicity has made abundantly clear.

This situation is basically one of the conditions of possibility for shows like documenta 14, in which the vast majority of contemporary work wants to do something other than merely exist for the impartial contemplation of its audience. Many visitors to Kassel report being somewhat overwhelmed by the show, and this is surely in part due to the volume of information it expects viewers to process, whether in the form of wall texts, supplementary discourse, archival displays, or simply the artworks themselves, many of which come laden with all manner of backstories.

As one moves through the exhibition, one doesn’t always know whether to see the artworks or to readthem—to focus one’s attention on experiencing affects or on decoding and interpreting messages. This tension can be productive but it can also be distracting or enervating, and at times one can sense the curators’ struggle to know how much contextual information to provide. (The fact that some people claim there was too much, while others argue the opposite, only suggests that this war is basically impossible to win.)

Part of the reason that heteronomy proves so difficult to negotiate is that it radically impacts not just the form and content of art, but its definition, indeed its very ontology. Art now exists in a much different cultural and economic space than it used to even 25 years ago, and while it has taken successful advantage of this shift it doesn’t always recognize its own limitations, or the discrepancies between what it wants to do and what it actually can do—or, for that matter, what it inadvertently does. It only compounds the problem that the models of self-reflexivity that were first developed around critical postmodernism generally aren’t suited for this task.

These profound contradictions are at the heart of the argument that Szymczyk and his team are trying to make, which assumes a fundamental congruence between art and politics—in this case a kind of left-liberal social democratic humanitarianism, in which art can serve both as a means of intervention and a kind of reparation. Exhibitions like documenta 14 (here closely following the example of documentas 10 and 11) don’t just make this one major conceptual leap; they take another one by proposing an alliance or even an identification between aesthetics and ethics. What’s more, they typically do so without rationalizing or even always explaining these maneuvers to their audiences, many of whom regard debates about art to be pretentious, intimidating, or just irrelevant, but whose cooperation is needed if any kind of concrete political or ethical effects are to be realized.

At this point it’s not really possible to be “for” or “against” this reorientation, which probably influences every biennial to some degree or another. That said, it would seem that one of the most important things criticism can do at this moment is to register and problematize the many effects of this ongoing, elemental transformation. In Kassel, as in so many other places now, one of the most obvious markers of art’s ethico-political turn is the ascendant genre that should probably be called “humanitarian kitsch.” (Ai Weiwei’s much-maligned 2016 photograph of himself posing as the drowned Syrian boy Aylan Kurdi is the most infamous exemplar to date.) Such work is often not just sentimental but emotionally manipulative, valorizing the artist’s sensitivity and glorifying subjective expression while leaning hard on viewers’ shock, sorrow, and outrage.

Humanitarian kitsch can be ignorant or naive in suggesting that intractable social problems have simple solutions that art can facilitate, typically by consciousness-raising. It can blur the boundaries between pity and condescension, sadism, or disgust. It can be obvious or even glaringly direct, like Miriam Cahn’s sometimes-ghastly paintings of various violent scenarios, which for some reason merit an entire large gallery in the Documenta halle. It can fetishize memory and trauma, like Bonita Ely’s doleful installation Interior Decoration: Memento Mori (2013-17), which featured weapons and prison camp scenes built from childhood toys, and which conflated numerous historical instances of collective violence while making problematic assumptions about how trauma is shared and transmitted.

It says something that such art is hard to dislike, not because its flaws aren’t plainly apparent, but because one feels guilty for doing so. This is one place where ethics and aesthetics are clearly in conflict: because these artists (some of whom are themselves survivors of the atrocities they depict) are almost always sympathetic figures, and because the issues they engage are unquestionably pressing, we’re somehow betraying the cause if we don’t care for their art. Even worse, we might be “called out” and brought before the tribunal of left-liberal social media to be sentenced to some kind of quasi-Maoist aesthetic re-education. This pressure isn’t the same as emotional blackmail, but it’s not necessarily that far off.

It’s in no way the case that the artists or curators involved with this documenta knowingly mean to exploit this dynamic, as some critics basically charge. All the same, one can’t extricate the exhibition (or the larger discursive-institutional sphere it inhabits) from the operation of different kinds of normativity, and therefore from more structural power relations. While appeals to guilt can’t be ignored entirely, particularly as they reactivate a latent religiosity in art, it seems much more plausible that shows like Szymczyk’s solicit a type of normative affect that works in tandem with liberal narcissism.

To caricature a complex, largely unspoken rhetorical operation, it is as if such exhibitions are making viewers a kind of subliminal promise, independent of whatever their curators might say or believe: We know that no one really wants to spend their leisure time doing something that reminds them of church or school or community service, but your choice to come here will make you a better person in a way that a beach vacation never will. You’ll have a powerful emotional experience, you’ll learn all sorts of things your friends don’t know, and you’ll go from being part of the problem to being part of the solution.

Not everything about this logic is necessarily corrupt, and of course this isn’t the only appeal that these shows make. But it’s nonetheless clear to see how such thinking can easily lead to different troubling scenarios: the not uncommon phenomenon of overidentification, where privileged audiences basically fall in love with their own empathy and/or those they wish to help; situations where art generates moral capital for artists and catharsis for viewers, but does little if anything for those it depicts; the problem of self-congratulation, in which the virtuous pleasure of performing one’s own enlightened bourgeois cosmopolitanism obscures one’s awareness of whatever crisis is supposedly in question.

None of these issues dominated documenta 14, but neither were they entirely absent. The clearest sign of their presence was the single biggest work in Kassel (and Athens, for that matter): a reconstruction of Marta Minujín’s landmark public performance-installation The Parthenon of Books (1983), which ironically memorialized Argentina’s recently fallen military dictatorship by building a temple from some 25,000 books the junta had banned. It takes nothing away from the considerable power of the original work to question what exactly it accomplished—apart from flattering the consciences of liberal viewers—to reproduce it in 2017 under conditions in which the industrial-scale manufacture of “fake news” poses much more of a threat than censorship does.

12. From early indications, it would appear that documenta 14 will be remembered by some as a chaotic overreaching mess, yet by many others as an intervention that is worth the considerable trouble of coming to grips with it: a genuine moral victory, if also an ambiguous, frustrating, or partial victory. It could well be that this will go down as one of the most divisive editions, given the current range and intensity of opinion. Various reasons might be offered to explain this lack of consensus: the event’s sprawl was such that few people really saw the same show; serious difficult political art is rarely a crowd-pleaser; the curatorial argument was either too ambitious or just incoherent (an impression fostered by the curators’ reticence and ambiguity, along with their more understandable aversion to reproducing hierarchies by instructing audiences or putting their own words in artists’ mouths).

Perhaps the simplest assessment one could make of this documenta is to say that it raises questions it can’t always answer. This is meant as both criticism and praise: criticism because in some cases such problems are essentially practical (insufficiently defined objectives, uneven execution); praise because in others the show engages issues that are at once vitally important and ultimately unresolvable, at least by any conceivable exhibition (the persistence of gross injustice throughout history, the ongoing global crisis, the contradictions of contemporary art).

Given the wave of international criticism that surges every five years, like some kind of periodic tropical storm, anyone can see how the position Szymczyk will soon vacate is at once the most and least desirable job in contemporary art. With this in mind, it seems only fair to recall that no exhibition can be anything more than a record of what its curators were ultimately able to do—it can never show what they wanted or tried to do, but for logistical or institutional reasons beyond their control were unable to. In this sense, one could say about curating what the US President Lyndon Baines Johnson famously said about politics: that it is “the art of the possible.”

To reach for another folksy American metaphor, we might reasonably conclude that Szymczyk and his team have bravely ventured to swing for the fences, and that even if the ball didn’t make it out of the park, it still went a long way: a solid double, maybe a triple. Will this documenta enable hundreds of thousands of people to see aesthetically compelling and thought-provoking art they would never have seen otherwise? Unquestionably, and by the most basic measure of popular impact that makes the show some kind of success.

Even so, it seems just as true that the exhibition largely fails when it comes to the difficult but essential task of critically and creatively responding to its own limitations. One wishes it had more to say about the way art institutions, documenta included, can reinforce or reproduce inequality at the same time they mean to eradicate it; or about whether there are situations in which art can’t or shouldn’t claim to speak for subaltern populations; or about the yawning, seemingly unbridgeable gap that exists between the sort of enlightened global counter-public sphere it imagines and the starkly repressive realities that currently prevail. One wishes this documenta had found better ways to contest, or even just illustrate, its own entanglement within the EU’s neoliberal debt regime, or its instrumentalization by a center-right German state eager to supplement its growing economic and political power with the soft power of cultural and moral leadership.

Perhaps the most anxious-making concern is the possibility that this documenta’s vision of emancipation in fact functions as a kind of alibi for the same social order that keeps such hopes from actually being realized. In such a scenario, art effectively compensates for the very inequalities it wishes to overcome: instead of a workable alternative to punitive austerity policies, Germany gives Greece the lesser half of a mega-exhibition, along with the opportunity for viewers, the minority of whom will be Greek, to “learn” from it. Or, as is the case in Kassel, exhibitions can make beautiful, moving apologies that lack any legal authority or popular backing.

It takes a certain sort of left utopianism to plow ahead in spite of such prospects. While this mindset is in some ways admirable, and can’t simply be written off as magical thinking, it nevertheless displays a clearly theological character in its longing for a kind of restitution, redemption, or transcendence against all indications to the contrary. One is reminded of Adorno’s famous rebuke to Benjamin: avant-garde art and its fellow travellers aren’t elements of some revolutionary dialectical synthesis; rather, they are the broken pieces of a lost freedom that can’t be reassembled.

Part of the reason this documenta can’t meaningfully reckon with such possibilities is that it seems curiously unwilling or unable to exploit art’s extensive capacities as a mode of negation. Despite the preponderance of ethically or conceptually demanding work, difficulty rarely becomes manifest at the level of form, whether as formlessness, opacity, equivocality, or any of the other tactics that were championed by the more intransigent modernist avant-gardes, and which still remain relevant despite their conventionalization.

Viewers are typically addressed as equals or as allies, and rarely as the subject of ambivalence, desire, or antagonism, or in a way that acknowledges the enormous gap between this art’s ideal audience and its actual audience. There are few instances in which one’s experience of the work feels charged, disorderly, or hard to anticipate—less like an appointment and more like a confrontation or an encounter.

13. Among the many valuable lessons one can learn from documenta 14, perhaps the most important is that contemporary art will need all the tools at its disposal if it hopes to more effectively negotiate the systemic contradictions that make its position at once so promising and so precarious. In its most perceptive moments, the exhibition begins to develop the sort of radically critical, quasi-dialectical strategy that the current conjuncture so clearly demands. Despite all the domination and trauma in this documenta, it is ultimately a resonant affirmation of freedom: not the techno-libertarianism of digital capitalism or the star-spangled assault rifle brandished by American neo-nativists, but the emancipatory realization of collective potential heralded in such stirring fashion by the likes of Schiller, Marx, and Fanon.

Toward this end, the show’s curators have pushed the biennial format about as far as it can likely go. They have granted new levels of funding, visibility, and latitude to a number of excellent but underappreciated artists, some of whom (Arin Rungjang, for example) have developed work they couldn’t have made or freely shown in their home countries. This deserves real respect, especially in a contemporary art world where freedom is still often equated with white male privilege and mega-yacht-level wealth—witness Damien Hirst’s most recent hyper-expensive monument to his own obscene, pathetic ego, the surpassingly idiotic Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, which was held at a luxury magnate’s private palazzo in Venice in a colossally vain attempt to upstage the Biennale. (It will surprise few and should horrify all that Hirst’s reported budget of 50 million pounds was nearly twice that of THIS ENTIRE DOCUMENTA.)

It should be enough that this documenta uses its own considerable privilege and freedom to accomplish numerous worthwhile things, despite its equally numerous flaws and problems. It should be enough, and yet one can’t quite shake the uncomfortable feeling that it isn’t. Perhaps this is because the show and most of the artworks it exhibits are essentially promising things they can’t deliver—things that can’t ever be delivered, at least by art or in the world we currently inhabit.

This isn’t in any way to blame them; who among us hasn’t wanted desperately to believe in heaven, or in revolution, or even simply in peace? But it is to insist on the need for an art (and a politics, and an ethics, and a theory) that will openly embrace a Gramscian struggle to counterbalance optimism of the will with pessimism of the intelligence; an art that can be lucid about its own contradictions and unfreedom even as it freely commits itself to the outer reaches of the possible.

- Discussions of documenta typically attribute this sort of thinking to Enwezor, but it hardly detracts from his accomplishment to note that documenta 11 essentially brought Kassel up to date with developments that can be traced back at least into the 1950s: the ventures of Tricontinental solidarity culture that emerged from the Non-Aligned Movement, like Third Cinema, the journals Lotus and Souffles, and the Bienal de la Habana; journals like Black Athena and Third Text, in which postcolonial theory was integrated with hybrid practices like the British Black Arts Movement; the wave of new biennials founded outside the global North in the 1990s. ↑

- See for example Walter Mignolo and Madina Tlostanova, Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas (Columbus, OH: Ohio State UP, 2012). ↑

- This text might itself be read as a symptom of what it describes, since it focuses on the Kassel show out of necessity, as the reviewer could only budget enough time to visit one mega-exhibition. ↑

- All works are dated 2017 unless otherwise noted. ↑

- Hanno Rauterberg, “Im Tempel der Selbstgerechtigkeit,” Die Zeit, June 13, 2017. Archived online at: http://www.zeit.de/2017/25/documenta-kassel-kunst-kapitalismuskritik. ↑

- For an informed discussion of the cultural politics of the Gurlitt collection, see: http://www.documenta14.de/en/south/59_the_indelible_presence_of_the_gurlitt_estate_adam_szymczyk_in_conversation_with_alexander_alberro_maria_eichhorn_and_hans_haacke ↑

- For an account of the relations between the founding of documenta and the cultural politics of 1950s West Germany, see Andrew Stefan Weiner, “Memory Under Reconstruction: Politics and Event in Wirtschaftswunder West Germany,” Grey Room 39, Fall 2009. ↑

- See “‘We Come Bearing Gifts’—iLiana Fokianaki and Yanis Varoufakis on Documenta 14 Athens,” art-agenda, June 7, 2017, archived online at: http://www.art-agenda.com/reviews/d14/. ↑

- A listing of all the artists shown in the venue, along with descriptions of their works, can be found here: http://www.documenta14.de/en/venues/21725/naturkundemuseum-im-ottoneum ↑

- For criticism of this documenta’s supposed fetishizing tendencies, see Susanne von Falkenhausen, “Get Real,” Frieze, June 7, 2017; archived online at: https://frieze.com/article/get-real-0. ↑

Read more about documenta

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario