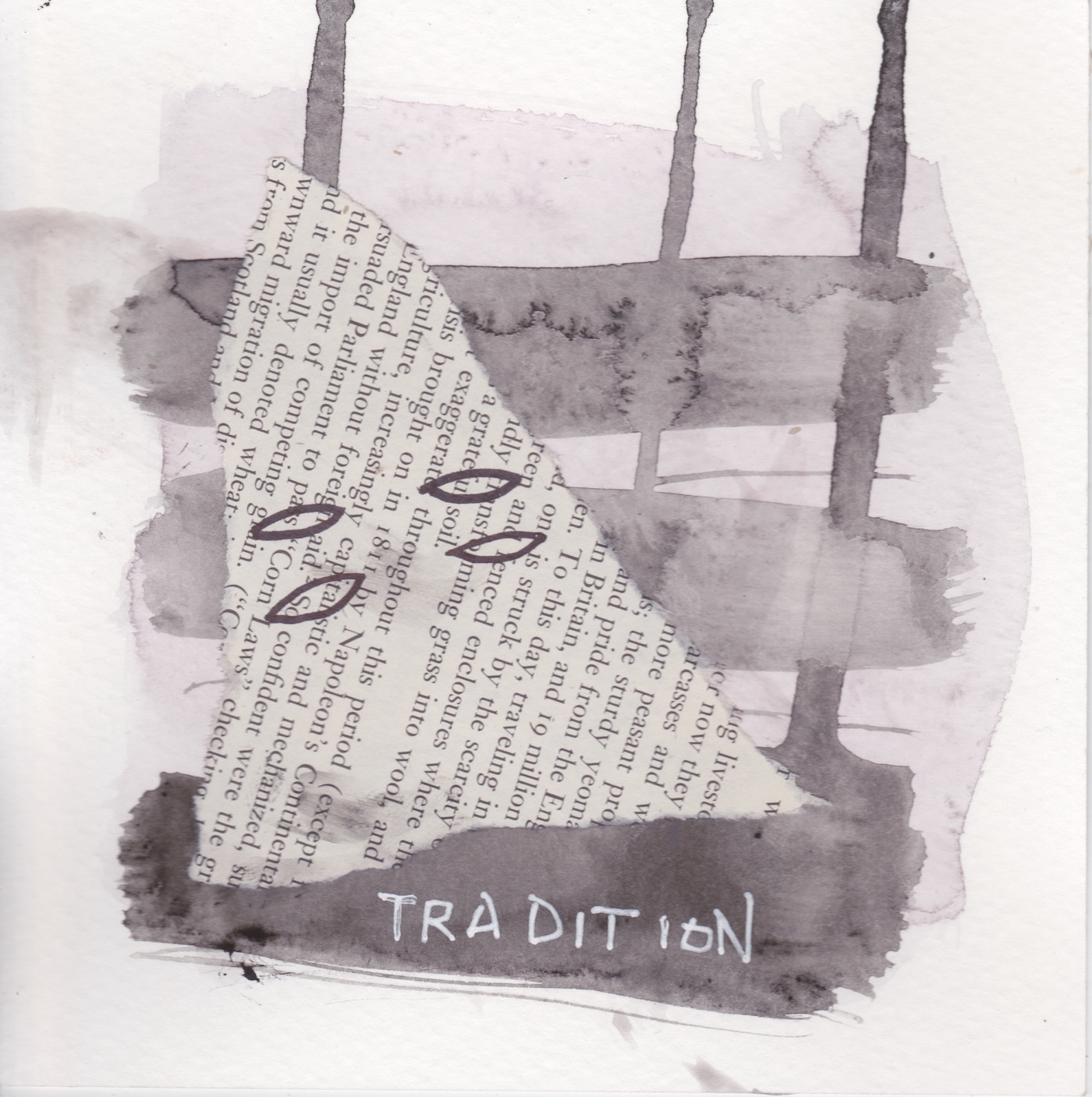

Damon Davis, “Negrophilia” (2015) (courtesy the artist)

ST. LOUIS — What does accountability look like in a world where no one is accountable? I recently attended an artist talk by Kelley Walker, a New York-based artist who has had an illustrious career, showing his work all over the world so far. I had heard about his show at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis and the type of work I would be seeing; Walker uses KING magazine covers featuring Black women and iconic Civil Rights-era photos in his work. He smears chocolate and toothpaste on the images and rotates them. Some of the titles of his work are “White Michael Jackson” and “Black Star Press.” So, knowing this, going to this artist talk, I just knew that this guy (this white guy) would have some sort of critical analysis around using such traumatizing material. Especially in 2016, when we are in a full-fledged rebirth of the Civil Rights movement; especially in St. Louis, the epicenter of this movement sparked by the Ferguson rebellion for the death of Michael Brown two years ago. Kelley Walker uses images of Black men and women to say something; but Walker doesn’t know what that “something” is.

I sat in the audience listening to this man meander on and on to the crowd, interjecting the occasional art term like “form” or “color,” but never once giving the slightest explanation for why he used over-sexualized images of Black women and traumatic images of Black men being brutalized by police and dogs. As I listened to him talk, I started to realize why people in my family think art isn’t for them and that it was a bad decision for me to become a professional artist. This guy is why the art world is viewed as classist and not for people of color, working class people, and why you hear brilliant people say things like, “I’m not an art person, I just don’t get it” — because there is nothing to get in art by people like Walker. This under-planned, poorly executed, elementary level artwork that uses Black women and men as props and controversy starters is over-intellectualized by classist, utterly inept, pompous, and clueless curator types. The world of art gets no more white and privileged than this.

Once the meandering stopped, it was time for questions and answers. Customarily, in a Q&A, an audience member asks a question and then the artist answers it. The Kelley Walker Q&A went a little differently. Not a single one of the questions asked ever got answered by the artist, no matter who was asking it or what it was about. High school art class questions, like “Who is your audience?,” were met with: “I don’t know.” “Why do you call these works paintings, when they are photographs?” was met with: “I’m tired of repeating myself.” One question that went unasked was: did the curator Jeffrey Uslip explain the process of a Q&A session to Walker? Who knows. Other Black artists beside myself were in the audience. A colleague, Kahlil Irving, asked, in reference to the images of Black women and men: “Why did you chose those particular images?” Walker’s response was something to the effect of, “I only use an image of one Black person in this show, and I will let you decide which image that is.” When Irving replied, “You didn’t answer my question,” he was told: “Yes, I did.” This childish display only escalated when I posed my question. I asked: “Why would you bring this stuff here given the racial climate of St. Louis and America, and I hear you constantly talk about capitalism as a part of your work but you don’t mention what role race and sex plays in it?” This infuriated Walker. He said things like, “Aren’t we all capitalizing of someone?” and “Who is toothpaste hurting?” This adult man threw a tantrum because normal people who had lived through scenes like the ones he chose to use for “aesthetics” were asking for some explanation. I am a professional artist. I make work that is controversial. I stand by everything I make because I think it through thoroughly before I release anything to the public. I also know going into an artist talk that I will more than likely be asked difficult questions. Walker did none of these things in preparation for this show. He was arrogant and disrespectful to a crowd of people, and paid by an institution to do so.

It is time for a new standard. People can no longer be allowed to exploit, demean, and disrespect a community and its history. Walker is the epitome of white male privilege, colonizing images of us that are either painful or sexual — both tantalizing to his audience — and then, when confronted, cowering and hiding behind artistic expression and his right as an artist to not be censored.

While the exchange of words was happening between Walker and I, the exhibition’s curator, Jeffrey Uslip, stepped in. “I think I can explain what Kelley is saying,” he interjected. I replied, “You didn’t make the work, he did.” Uslip didn’t give a clear answer either, and in other contexts he has praised Walker for his analysis of race, gender, and modern culture. So, an institution of this stature brings in an artist who can’t even tell me why he rotated an image to give it “new meaning,” and then the curator has the nerve to try to shield him. There is no deeper meaning behind the work other than Walker’s obsession with Black people and culture. He gets on stages all over the world and spews meaningless chatter at audiences of insulated, wealthy white people who just nod their heads in agreement to ignorance.

I am a proponent of free speech and artistic license; I sample, I collage, I build upon ideas. What I am not a fan of is carelessness, exploitation, and lies. How this man has been able to build a successful career and never be challenged by someone from my community escapes me. But here, in tiny, uncultured, uneducated St. Louis, lives a community of people who aren’t standing for this charade any longer. If you don’t respect your audience, if you don’t even know who your audience is, you don’t deserve one. Institutions have to hold artists accountable for how they approach the work and how they treat their patrons, and if an institution can’t, it needs the be held accountable for its negligence.

Black people in America are treated as commodities and targets, never human beings that deserve the slightest amount of dignity or respect for the trials that this country has and continues to put us through. Art is the most powerful thing in the world. Mass media and art were among the Nazis’ most coveted tools. Now, what if I took pictures from the Holocaust and smeared cream cheese on them and threw them in a frame, and then told you it was a critique of capitalism and an exercise in color and the form of the contemporary modernist landscape? Then the guy who hired me tried to spin what I just told you into a profound analysis about race and anti-semitism? And all this was happening at an art gallery in Germany, not far from the site of a concentration camp. What would the world say? Nothing, because THAT WOULD NEVER HAPPEN. I charge everyone who cares about art and culture to hold us all accountable — the artists, the curators, and the institutions. I also would like to personally extend an invitation to Walker — and anyone else — to come to my artist talk at MoCADA on October 22. He can hold me accountable. That is the only way we grow as a society and a profession.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario