Installation view, ‘The Art of Romaine Brooks’ at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (image courtesy the Smithsonian American Art Museum) (click to enlarge)

WASHINGTON, DC — Tucked into a far corner of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), an exhibit showcases the extensive career of artist Romaine Brooks, a turn-of-the-20th-century icon who’s since been largely forgotten by the mainstream. The three rooms that make up the modest but wide-ranging show The Art of Romaine Brooks are sparsely hung with paintings and drawings from the museum’s collection; Brooks donated a large number of her works to SAAM shortly before her death in 1970. Spanning her entire career and delving into the gender politics she enthusiastically rejected, the exhibit is a fascinating glimpse of lesbian subculture in the early 1900s, brought to life in Brooks’s evocative, darkly hued style.

Romaine Brooks, “Self-Portrait” (1923), oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the artist (click to enlarge)

Romaine Brooks, whose real name was Beatrice Romaine Goddard, was born in 1874 into both deprivation and privilege. Her childhood was overshadowed by a mentally ill brother, to whom her mother was devoted. Brooks spent most of her life grappling with the scars of a lonely, affectionless, and abusive childhood. But she did have one significant advantage that defined her professional and personal life: her family was immensely wealthy, and she was the heir to their fortune. In 1902, she was able to claim her inheritance, and with the money came a freedom that she used to live and work as she pleased in Paris, Rome, and Capri.

Brooks’s wealth afforded her a latitude of which other women at the time could only dream. She was free to shake off the restrictive expectations of women artists, including female nudes in her early exhibits and taking classes in which she was the only woman. After a brief, tumultuous marriage to John Ellingham Brooks, she rejected monogamy and, largely, men, even as subjects. In 1915 she met Natalie Clifford Barney, a leading host of salons in Paris, and the couple began a five-decade nonmonogamous relationship. Despite their deep bond, the two women maintained near total independence, living in a home with separate wings and both having relationships (some serious) with other women.

In an era still dominated by men, Brooks leaned into the subculture to which she belonged and painted largely her own friends and lovers. The exhibit at SAAM has several of her stormy yet intimate portraits of women, including one of Hannah “Gluck” Gluckstein, an artist who eschewed gender via a mode of dress that was both fashionable at the time and a signal of her sexuality. Gluck and Brooks were part of a growing but still little-known group of women who wore men’s clothes and cut their hair short not just to embrace the 1920s androgyny trend, but to communicate to others in the know that they were lesbians.

Romaine Brooks, “Peter (A Young English Girl)” (1923–24), oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the artist

Brooks’s portrait of Gluck, a centerpiece of the exhibit, is an incredible painting that captures the masculinity of Gluck’s style and the femininity that existed alongside it. Titled “Peter (A Young English Girl)” (1923–24), the work is a classically posed portrait showing its subject in profile, her hair swept back and her menswear dark. With just a passing glance, it would be easy to mistake Gluck for a man. But upon closer examination, there’s something about her features — a confidence and sharpness, as well as a delicacy — that transmit as deeply female. One gets the sense that Brooks respected her subject deeply — a respect that’s present in all her work and imbues it with a quiet intensity. There’s also a sense of movement that brings her subjects to life, as if they were about to walk off the canvas or shift slightly in their seats.

Brooks’s own emotions run close to the surface in all her work. Her early paintings, which include portraits of wealthy aristocratic women, reflect a sense of constriction and self-conscious modesty. The subjects turn away from the viewer, while the softness of the brushstrokes blurs them ever so slightly, a stark contrast with the definition in Brooks’s later work. Two nudes from the beginning of her career show different approaches to painting women and pose questions about the way we consume the nude female form. “The Red Jacket” (1910) draws the viewer in even as the subject looks off into the distance, her pose suggesting sadness and discomfort. The softness of Brooks’s lines and the vulnerability of her subject imbue the work with a sense of voyeurism. In contrast, the subject of “Azalées Blanches (White Azaleas)” (1910) lays casually on a sofa, her face betraying little interest in how she’s being seen or shown and exuding a confidence beyond sexuality. The next year, Brooks painted a nude portrait of dancer Ida Rubinstein in which the subject lays on a white surface offset by a dark background, looking sensual and relaxed. Rubinstein’s gaze is turned away like those of the other nudes, but there’s a new warmth and contentment here. The evolution of Brooks’s work reflects a growing awareness of the way the artist’s and viewer’s gaze influence our understanding of the subject’s identity.

Romaine Brooks, “Azalées Blanches (White Azaleas)” (1910), oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the artist

Romaine Brooks, “Unity of Good and Evil (Unite du Bien et du Mal)” (1930–34), pencil on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the artist (click to enlarge)

The final and most extensive section of the exhibit showcases Brooks’s drawings, most of them completed between 1910 and 1973 to complement her unpublished memoir, No Pleasant Memories. They show humans grappling with skeletons, in captivity, and tormented by nightmarish ghouls — a direct attempt to contend with her childhood and themes of death and constriction. Her drawings are surreal, most of them seemingly made from single, continuous lines whose fluidity undercuts their darkness. Brooks’s close attention to detail, such as the fingers on a nebulous Death or expressions of horror on figures held captive, makes the works jarring yet visceral. They’re especially jarring in contrast with her portraiture, which suggests a real strength and comfort among friends and partners, as opposed to the lasting childhood trauma manifested by the sketches.

While at times frustratingly sparse, SAAM’s exhibit offers an effective cross-section of Brooks’s work, influences, and passions. The large-scale portraits are striking and engaging, and although one comes away wanting to see more, in this uncrowded setting, the works that are on view are able to shine without distraction. A century later, Brooks remains one of the most astute artistic observers of women and a solitary talent in capturing the spirit and strength of her subjects. Her ability to bring to life the juxtaposing forces within the women she painted sets her apart from her contemporaries; Brooks was a private figure shining a light on the margins of her own society. Her work continues to do so today, with compassion and affection, illuminating a group that quietly played a role in shaping the culture of the 20th century.

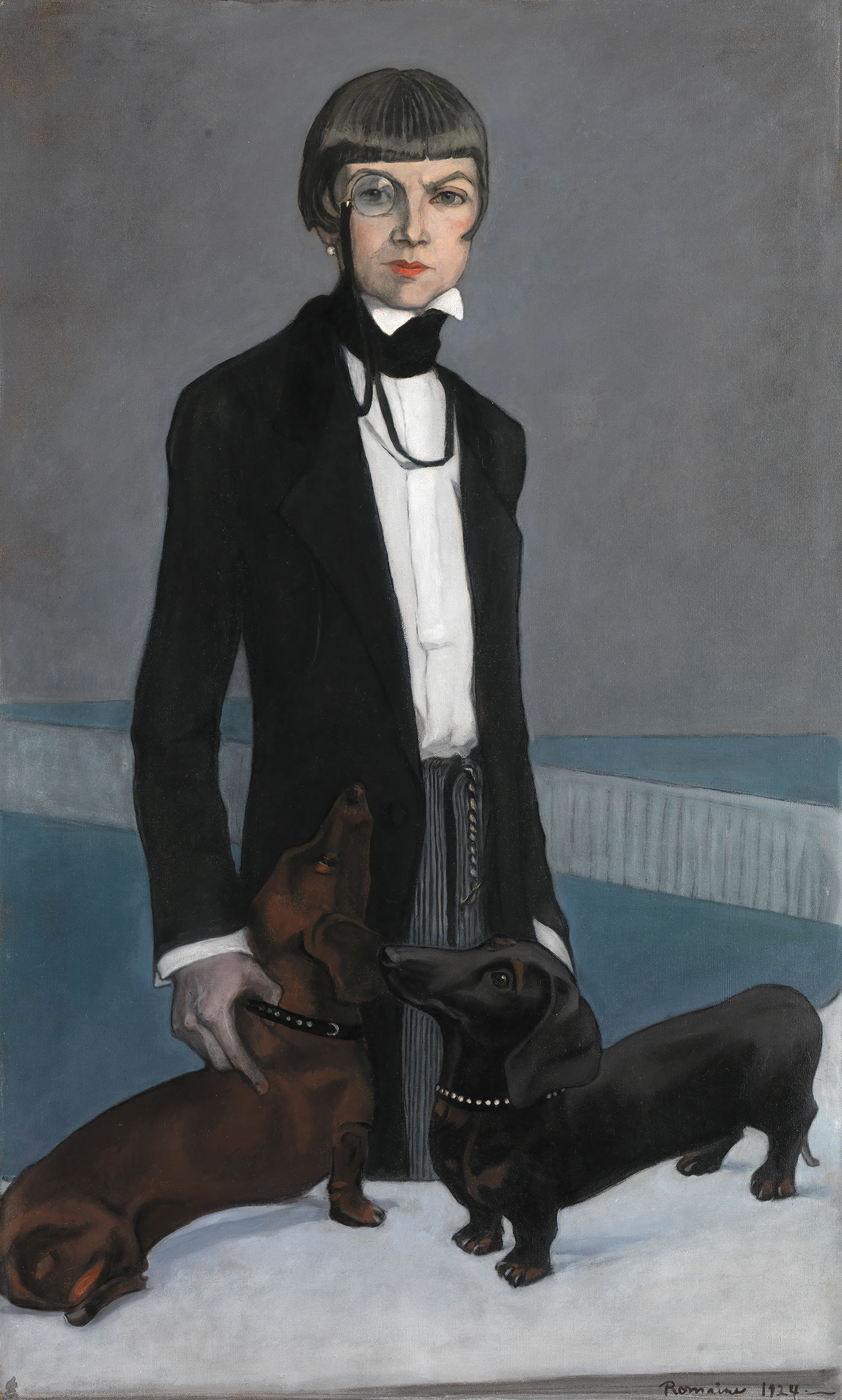

Romaine Brooks, “Una, Lady Troubridge” (1924), oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the artist

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario