Henri Matisse, Still Life with Blue Tablecloth, 1909. Collection of the State Hermitage Museum.

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Blue Tablecloth, 1909. Collection of the State Hermitage Museum.

In October 1897, a 27-year-old Henri Matisse attended a wedding in Paris. At the banquet that followed, he was seated next to a young French woman named Amélie Parayre. Each was completely taken by the other; they married less than three months later.

At the union of Monsieur and Madame Matisse that following January, among the wedding gifts the couple received was a chocolate pot from Albert Marquet, a close friend of the groom and a fellow Fauvist. This present, which Matisse may have used to make coffee as well as hot chocolate, would go on to appear in dozens of his works throughout his career.

Indeed, as the artist once said, “a good actor can have a part in ten different plays; an object can play a role in ten different pictures,” and this chocolate maker grew into one of his favorite stars.

Known as a chocolatière, the first French chocolate pot of this kind was created in the 17th century to prepare fresh hot chocolate drinks. While they began as a luxury item typically made from porcelain, after the invention of cocoa powder (which made the drink cheaper and easier to make), by the mid-1800s, chocolate pots became a household necessity.

But Matisse saw more in the chocolate pot than a way to satisfy his sweet tooth. He was undoubtedly drawn to the item’s design—its round, bulbous shape, protruding handle, and shiny, silver surface, which reflected the many vibrant hues of his studio.

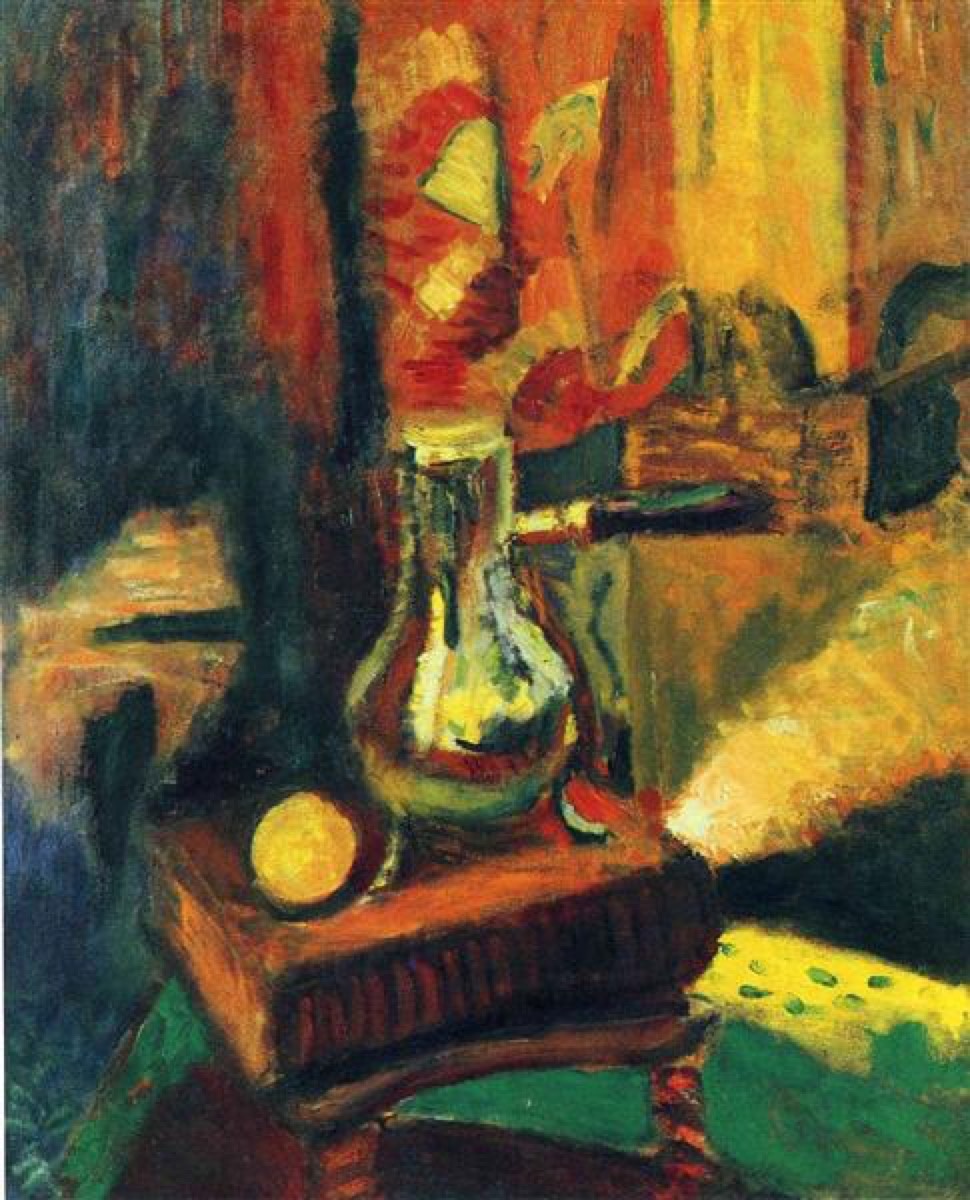

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Chocolate Pot, 1900.

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Chocolate Pot, 1900. Unknown, Coffee Pot, France, early 19th Century. Musée Matisee, Nice. Photo © François Fernandez, Nice .

Unknown, Coffee Pot, France, early 19th Century. Musée Matisee, Nice. Photo © François Fernandez, Nice .

“Like many of his personal objects, this one captivated Matisse for different reasons at different moments in his career,” says Ellen McBreen, co-curator of “Matisse in the Studio,” an exhibition of the artist’s personal effects alongside the works in which they appear at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. (It was organized by the Academy with the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and originated there.)

One of the earliest appearances of this wedding gift in Matisse’s oeuvre is Still Life with a Chocolate Pot (c. 1900–02), where it sits stately atop a hefty book on a stool. “Matisse captures [the pot’s] graceful form and silver surface, combining tradition with the contemporary color theory he was learning at the time,” says McBreen. “You can see that in the contrasts of pure color.”

Shortly after its debut, Matisse cast the object again in Bouquet of Flowers in a Chocolate Pot (1902), yet now in a different role—as a vase. As noted by Royal Academy curator Lucy Chiswell, here the pot is captured in three-quarter profile, much like a formal portrait. The bouquet it holds is a reference to his wife, and the floral arrangements she crafted for her Parisian hat shop, which opened a year after their marriage.

“I like to think of this painting as a subtle tribute to his wife,” McBreen says. “The entire still life takes on an anthropomorphic quality, as if it were a stately figure sporting one of those fashionable milliner’s creations.” (Interestingly, Pablo Picasso—Matisse’s friend and rival—purchased this painting in 1939.)

In contrast, the chocolate pot is much more discreet in Interior with Young Girl Reading (1905–06), wherein Matisse drowns it out amidst a Fauve color palette and quick brushstrokes. The “young girl” here is Matisse’s 11-year-old daughter. Indeed, it seems that the artist incorporated the chocolate pot into this paintings as a symbol of his family and domestic life.

However, after his striking Still Life with Blue Tablecloth of 1909—in which the chocolate pot appears before a busy monochrome pattern, alongside a vase and a plate of fruit—Matisse rather suddenly stopped painting the object for roughly three decades. During this time, he turned towards more figurative works featuring human figures, as well as a more simplified, pared-down style (see 1916’s The Piano Lesson, for instance, and The Pink Nude of 1935, or any of his odalisques).

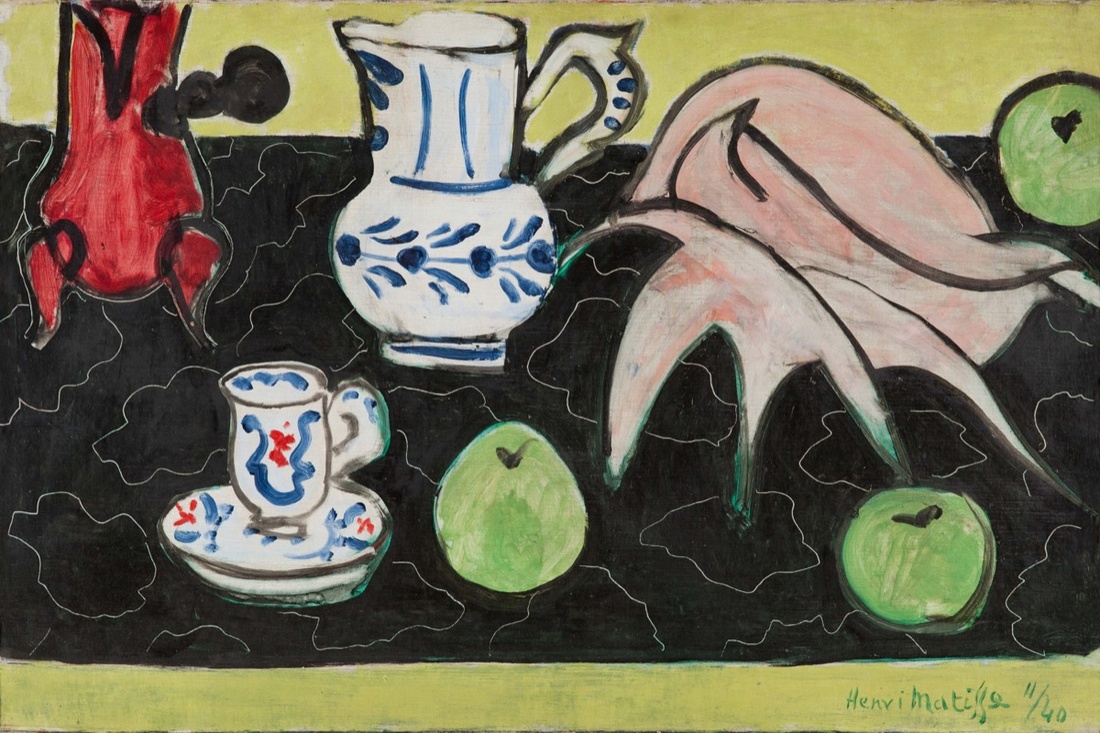

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Seashell on Black Marble, 1940. The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo © Archives H. Matisse. © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017. Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Seashell on Black Marble, 1940. The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Photo © Archives H. Matisse. © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017. Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts.

“Painting is not a time-based medium like music or theater,” McBreen notes, “so returning to the same object [after many years] helps Matisse to evoke the passage of time.” Though the reason remains uncertain, it may have been Amélie’s decision to leave her husband in 1939 that spurred him to return to the chocolate pot motif. It’s been reported that she was unhappy when her husband hired a 22-year-old studio assistant, who then fully replaced Amélie as the artist’s muse and caretaker. Whatever the reason, Matisse’s marriage of over 30 years had crumbled.

In his first post-divorce depiction of a chocolate pot, the object itself was also replaced—after the break-up, the couple had divided their belongings evenly, and Amélie evidently kept the original. Still Life with Seashell on Black Marble (1940) is both a reflection of Matisse’s artistic evolution in the decades since he last painted the object, and of the developments in his personal life.

Here the pot—which is smaller and has a different handle—is in the upper left corner, next to a set of porcelain and a scattering of green apples, along with a domineering pink Tahitian seashell. “Suddenly, the object’s interaction with its surroundings imbues it with symbolic meaning,” Chiswell wrote. Now, rather than symbolizing Matisse’s beloved relationship, here the pot comes off as an aside, a melancholy reference to what once was.

Despite his heartache, it was around this time, too, that Matisse found himself beginning a radical new path in his art. In planning Still Life with Seashell, he sketched the various objects on paper, then cut them out and used pins to put them in place. This allowed him to toy with the composition, before putting brush to canvas. In the end, he realized at least four versions of the still life, which he photographed over the course of three months.

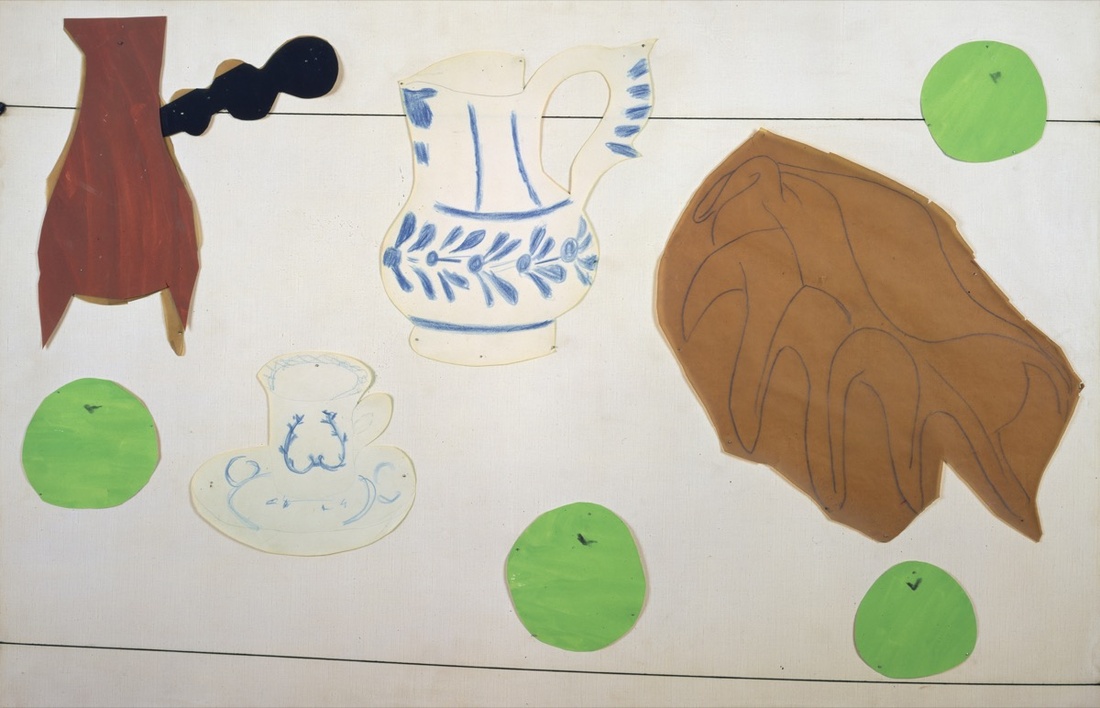

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Shell, 1940. Private collection. Photo © Private collection. © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017. Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Shell, 1940. Private collection. Photo © Private collection. © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2017. Courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts.

“We were very pleased to include [this work] in the exhibition, since it provides such vivid insight into how and why Matisse developed the cut-out process,” McBreen says, referring to the massive body of work the artist made using painted pieces of paper and scissors during the last decade of his life. “It shows that when he cut paper, it wasn’t always to make the kind of cut-outs with which we now associate late Matisse.”

Though the chocolate pot isn’t known to have reappeared after 1940, its importance both within Matisse’s art—and to the artist himself—is hard to ignore. He never explained why he depicted it so often, nor why he returned to it after the prolonged break, and McBreen reminds us that the artist’s work is not autobiographical in the conventional sense. “Frustratingly,” she says, “for viewers who are searching for connections to [Matisse’s] biographical details, his work will often end up leading you back to themes explored in the past.”

Yet, while Matisse painted many of his objects throughout his career—and prized them like good colleagues—it seems that his affinity for the chocolate pot came from the most intimate of places. After all, as the artist wrote while abroad in a 1920 letter to his then-wife, “[My] objects keep me company…I am not alone.”

—Kim Hart

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario