“One finds light best in the darkness” —Meister Eckhart

A great deal has been made of Rothko’s paintings over the years, less in terms of discourse than through the efforts of art enthusiasts whose self-appointed mission is to convince viewers that a rarified state of emotional content is latent within these paintings. I have heard comments to this effect on numerous occasions, especially in reference to the Rothko Chapel in Houston and to the extraordinary paintings that hang on perpetual view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. This kind of museum-style rhetoric implies that the viewer should find some kind of “spiritual” meaning beyond words, as if the paintings were meant to exist without critical thinking or had emerged without any conscious or discriminating intention on the part of the artist. An alternative approach would be to suggest that there is no easy access to Rothko — that to perceive these paintings in a meaningful way requires a sensory form of intelligence, a quality of perception (strangely overlooked in American art education) where the act of seeing evokes thinking in a way that differs from the way we look at things in everyday life.

My first occasion to see a significant exhibition by Rothko occurred during a trip to New York City in December 1970. I had met with a noteworthy painter who suggested I visit the memorial exhibition of last paintings at the Marlborough Gallery on 57th Street. Upon entering this formidable space, my first observation was that the paint on many of the unfinished surfaces was thinner than I expected, much different than the impasto surfaces on the Rothko paintings I had seen elsewhere. The ineluctable mixture of gray, brown, and black tones was impressive. Accompanying the exhibition was a selection of late sculpture by Giacometti, primarily the large-scale standing and walking figures. As a younger artist, I was taken by the poetic elusiveness between Rothko and Giacometti. The existential context of the installation seemed to encapsulate the dolorous, unexpected circumstances of Rothko’s death earlier that year, yet it concomitantly augmented the delicate force behind these intensely restrained final paintings.

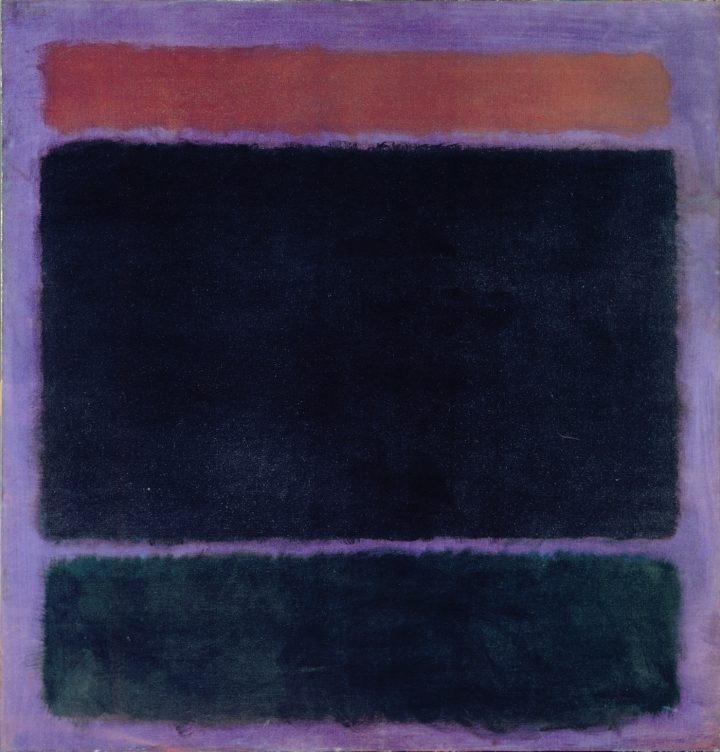

While viewing Mark Rothko: Dark Palette on three occasions at the Pace gallery in West Chelsea, I kept thinking of the word “sublimation” as it might apply to artists who work internally in reference to matching feelings with abstract imagery on surfaces. Sublimation is a Freudian concept that might apply to the kinds of inner conflicts felt by artists before they arrive at a meaningful resolution in a work of art. In Rothko’s case, the significantly dark-hued paintings, such as “Untitled (Dark Gray on Maroon)” from 1963, “Untitled (Plum and Brown)” from 1964, and “Untitled” from 1969, all of which are currently on view at Pace, appear to give evidence of Freud’s conjecture. Despite the differences in scale and time periods, the artist’s all-over balance of thinly transparent “light” on a variety of surfaces, including paper mounted on board and canvas or painted directed onto the canvas, and the deftly concentrated layering of the paint suggests a sense of completeness and confidence. In some paintings, like “Untitled (Plum and Brown),” the demarcation of the shape(s) on the surface is nearly indiscernible. One has to search for the beckoning structure that lies within the surface. The confidence, for Rothko, is revealed through his insistence on the presence of the light, even though it may appear absent at the outset. It is, in fact, if not ultimately, present.

60 x 57 in (photo by Hickey Robertson)

Even so, the density apparent in Rothko’s work, confusing to some viewers, may also relate to the “dialogical encounter” between the self and the other, once cited by the existential theologian Martin Buber. Here, as shown in “Untitled (Rust, Blacks on Plum)” from 1962, which confronts the viewer upon entering the exhibition, the initial opposition between the viewer and the work reveals three suspended, soft-edge, densely layered horizontal rectangles. As the color literally begins to take shape, the forms suddenly come together. To feel the manner in which color and obscurant light (within the confines of darkness) resonate in this painting would seem to require an extraordinary focus and commitment, an unheeded open-mindedness whereby some form of solitary transcendence might occur. But there is no formula by which to make an experience happen with a Rothko. Even so, one may hope that it is still within the reach of those of us conditioned by the speed (and, perhaps, the emptiness) of our constantly beckoning virtual reality.

The selection of paintings at Pace reveals the fundamental relationship between darkness and the artist’s oblique sense of light that appears barely visible. Yet one of the featured paintings in this grouping appears not to follow suit, namely “Section 6 (Untitled)” from 1959, otherwise known as the Seagram mural. “Section 6” was one of a precise aggregate of horizontal panels focusing on the color red with little residue of darkness. It was originally commissioned for the dining room of the Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram building and was completed the same year as the Rothko commission by architect Mies van der Rohe. Other sections of the Seagram mural are on permanent view in the superb collection at the Kawamura Museum near Sakura, Japan.

As the story goes, Rothko and his wife were invited to this enviable high-class restaurant to have a look at the location where his paintings were to be hung. Rothko, a stalwart democratic socialist, discovered that his mural would be located in an area outside of where most of the restaurant staff could see it. He insisted that the panels instead be mounted in an intermediate location accessible not only to the wealthy patrons but to the kitchen personnel as well. He was rebuffed and, as a result, he refused to grant the restaurant permission to hang the mural. To reinforce his adamant decision, he returned a major portion of the lucrative commission he had already received.

In the context of the ethos behind the Seagram mural, the opportunity to view Rothko: Dark Palette could not have come at a more appropriate time. In the past month, Americans suddenly became aware of the dire political situation presently confronting our nation and the world as a result of the 2016 electoral process. Are we, in fact, living through a time of the dark palette? Perhaps to know that the even the faintest light is still present within the current darkness may offer another point of reference: how we might retrieve a sense of the spiritual within a material world gone amok.

Mark Rothko: Dark Palette continues at Pace (510 West 25th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through January 7, 2017.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario