It’s been 12 years since the passing of Agnes Martin at the age of 92, and still her paintings remain as alive as when they were first conceived. The current retrospective of Martin’s work, now in its fourth and final venue at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, is stunning. It is an exhibition worth seeing on more than one occasion, and it will probably appear differently each time, because not every painting can be felt or understood to its fullest in a single viewing. Each visit opens up a wide range of encounters with Martin’s work, in which the subdued color, material refinement, exacting placement, and range of light become evident.

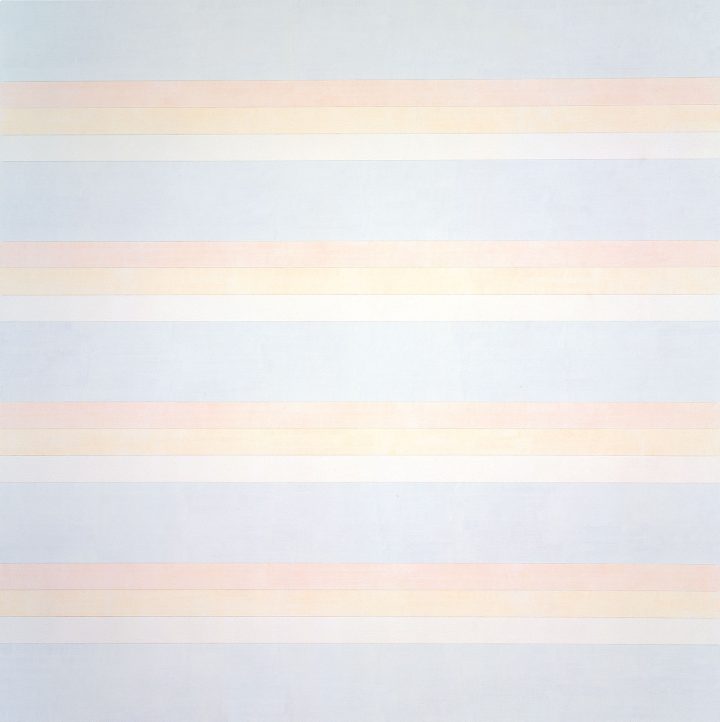

For instance, seemingly dark paintings such as “Untitled #8” (1989) and “Untitled #12” (1984), both in acrylic and graphite on canvas, transmit a kind of tangible aura as the retina makes contact with the light reflecting off the surface. It is this light that gives the gridded canvases their fullness and release of slow energy, similar to the experience of viewing some scroll paintings from the Song Dynasty. To observe the carefully modulated grids within and beneath the whiteness of Martin’s surfaces is to know the fundamental strength of these paintings, and to know that strength is to feel it.

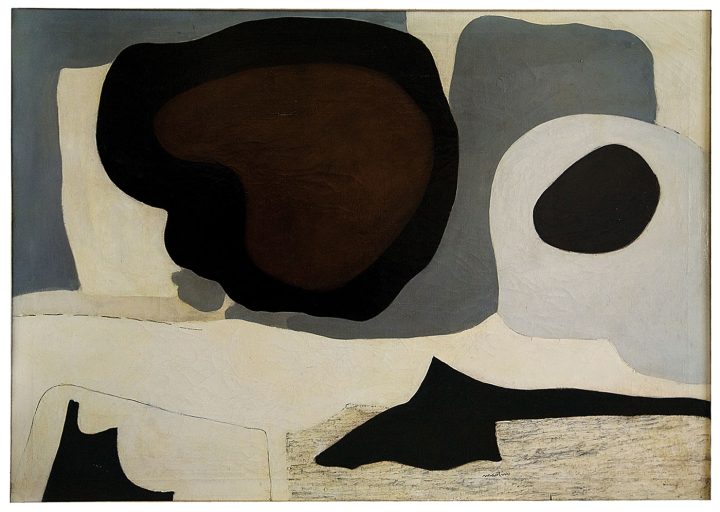

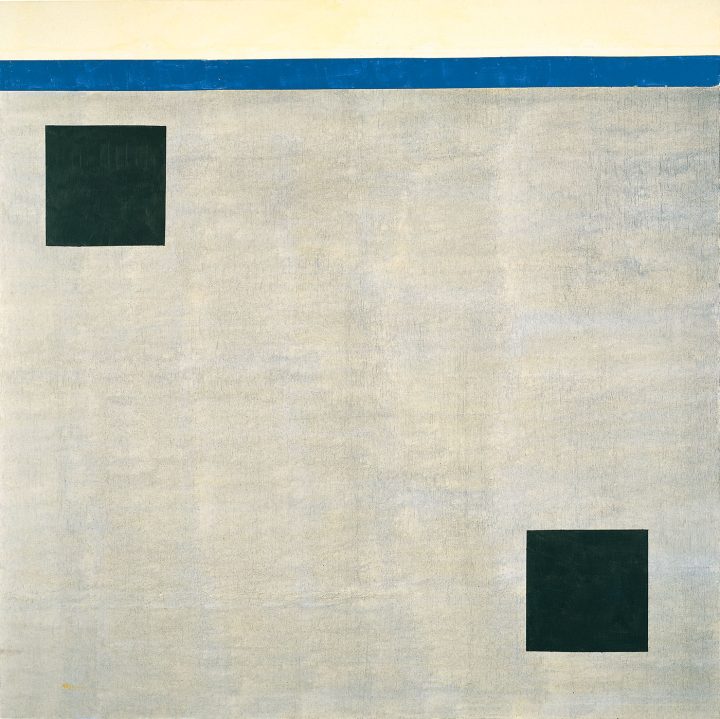

Once she discovered the grid in 1960, working in a communal studio on Coenties Slip in Lower Manhattan, Martin’s work began to carry a certain resolve and purposeful energy. Whereas the earlier paintings from the 1950s defined themselves through a geometry of simple shapes, the all-over uniformity in Martin’s “Untitled” (1960) — a 12-by-12-inch oil-and-ink grid on paper — allowed something else to happen. She let go of a sense of ownership, the idea that she was the author of the painting, as a new liberation set in that evoked the silence of stasis. (This occurred after a period of repeat nervous breakdowns in the late ’50s, while teaching in New York.) By the time she painted “Night Sea” (1963), a large oil on canvas in blue with gold leaf, measuring 72 by 72 inches, she had not only secured the calm she’d been seeking, but also formally decided on a consistent scale. The method she pursued was to repeat with soft pencil or sticks of graphite lines in both a vertical and horizontal direction, to the point where the surface of the canvas appeared to bring forth the kind of light and energy she sought. The surface on which she drew her thin, tightly spaced lines was then painted in oil, or, after 1974, in acrylic.

In 1967, the artist made an abrupt decision to leave New York and stop painting. After traveling around the western states in her truck for a year and a half, she chose to settle in Cuba, New Mexico, where she eventually returned to painting, in 1974, before moving permanently to Galisteo three years later.

After her hiatus, Martin began working with pale primary colors and matching values. Two illustrative examples in the exhibition from this restart period are “Untitled #8” and “Untitled #3” (both 1974). In both works, pale red and blue rectangles are placed alongside one another, but separated by thin strips of white and graphite lines, which make the canvases shimmer with a relaxed energy. They don’t jump out at the viewer; rather, they hold a quiet aura that stems from the dependable contiguousness of the rectangles within a square space. Martin would go on to transform her surfaces through color, less as embellishment than as a process of clarification and refinement.

Her prolific writings and comments often testify to her intentions with a remarkable sense of poetic articulation. In a talk given at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania in 1973, Martin said, “I paint about perfection that transcends what you see — the perfection that only exists in awareness.” She continued: “Why do we make works of art? The answer is that we are inspired to do so.” It’s curious that these words were spoken near the end of a long interval when she was not painting; however, 1973 was an important year for another reason. In April, she was invited by screen printer Luitpold Domberger to travel from New Mexico to Germany, where she produced a series of 30 screen prints of grids on Japanese rag paper, each measuring 12 by 12 inches. Titled On a Clear Day, the portfolio edition was printed by Parasol Press and shown later the same year at Yvon Lambert Gallery in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

There were two important outcomes of the portfolio project: Martin became “inspired” to begin painting again, and she clearly demonstrated, in the prints, what she meant by claiming her grids were rectangular. In an early interview, with critic Lucy Lippard for Art in America in 1967, the artist said, “When I cover the square with rectangles, it lightens the weight of the square, destroys its power.” She returned to the same idea in a late documentary, made by Mary Lance in 2002.

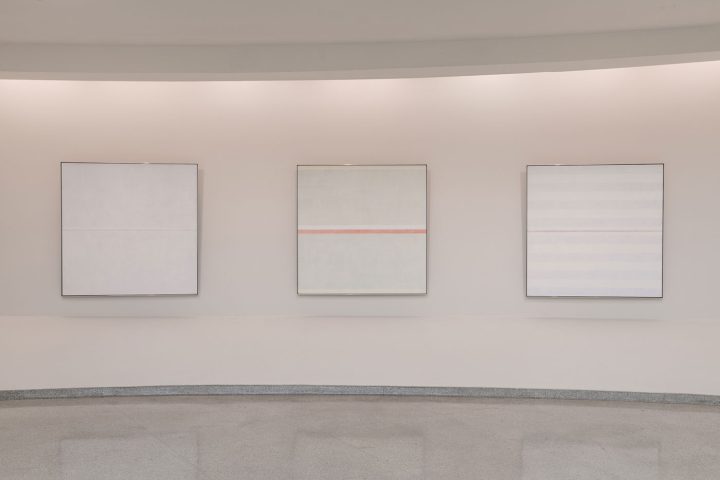

One of the most striking displays in the current exhibition features the 12 white paintings that constitute one of the artist’s major sets, titled The Islands (1979). These harmonious white paintings, each measuring 72 by 72 inches and painted with graphite and layers of gesso and acrylic, are spaced equidistantly along the walls of a curved alcove. Strategically placed at the end of the Guggenheim’s long entry ramp, the installation holds the viewer’s attention despite the lack of a clearly visible form. These refractive paintings must be observed closely in order to understand what they are. The graphite grids are difficult to see under the layers of paint, but they are still there. Standing before The Islands, one gets the sense that it’s not just the artworks in themselves but Martin’s palpable renewal of energy and inspiration that gives her lengthy late period the substance so many have recognized.

In a undated letter to her gallerist around this time (published in Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances, Phaidon, 2012), Martin talks about the differences between seeing a painting and perceiving it. To perceive it, she says, is to respond to a work of art in a way that suggests an experience. This is what differentiates the act of perceiving art from merely constructing an intellectual analysis wherein the mind is separated from the body. It is precisely this idea that gives her own paintings a sense of being about pure abstraction par excellence. What’s more, she very much believed that the artist should be isolated — that through isolation the chances of having an accurate perception of one’s work were greater than what one was likely to find in a social environment. Martin was a great believer in the artist as outsider — they should “stand against societies, conventions, and natural inclinations in order to do [their] work,” she said. This was probably her first motivation when she packed her bags and left New York in 1967, in search of a solitary life in the desert.

Elsewhere in her writings, Martin states: “Beauty is the mystery of life. It is not just in the eye. It is in the mind. It is our positive response to life.” At the Guggenheim, a strong message emerges from Martin’s magnificent works, whether paintings, drawings, prints, or even sculpture: to become a serious artist requires a choice, a willful rite of passage that precedes the course one will follow. This message reverberates with remarkable consistency throughout the rotunda.

Agnes Martin continues at the Guggenheim Museum (1071 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through January 11, 2017.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario