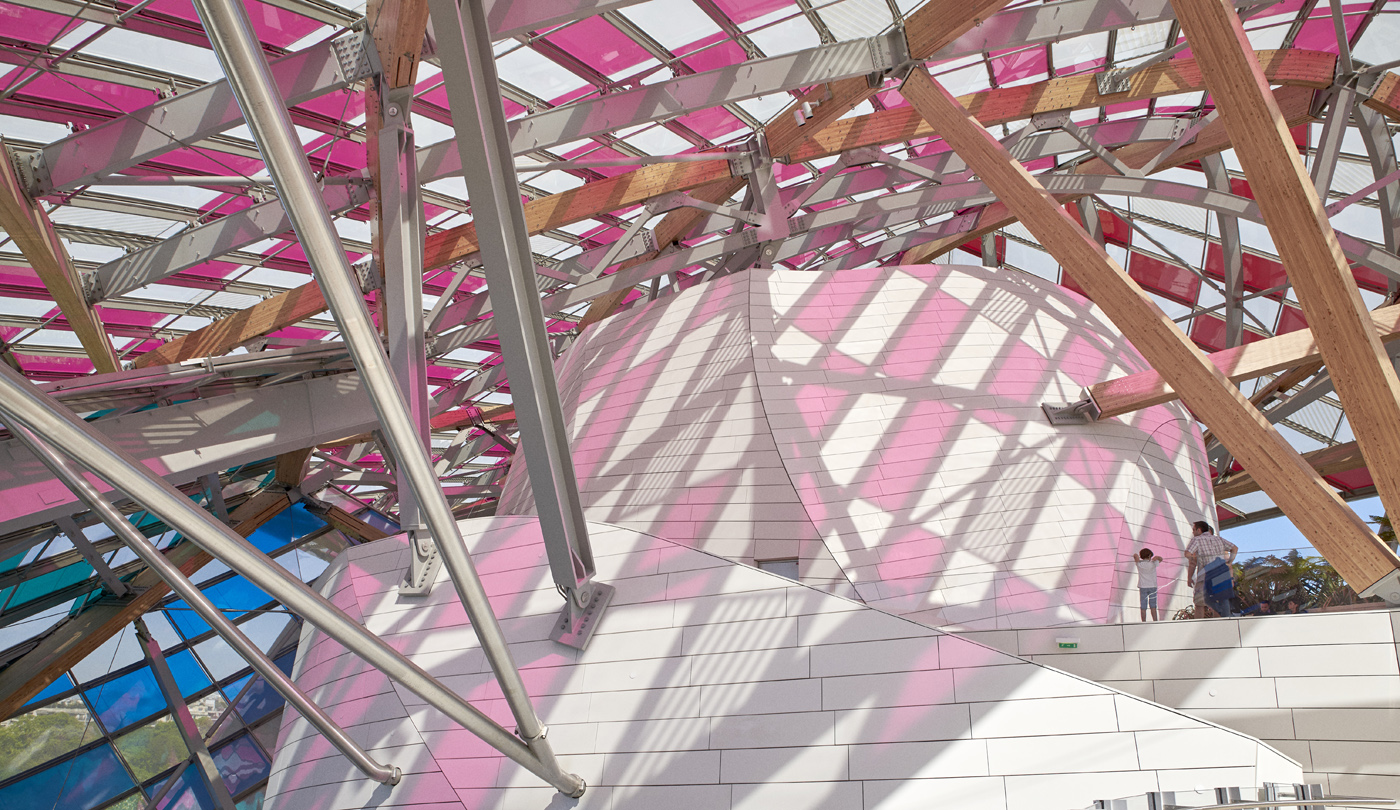

Daniel Buren, “Observatory of Light” (2016), work in situ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (© DB-ADAGP Paris / Iwan Baan / Fondation Louis Vuitton)

PARIS — Lacking any discernible content outside of context, the translucent, cheery façade of Daniel Buren’s “Observatory of Light” (2016) at the Foundation Louis Vuitton is another example of how once-radical conceptual artists have become co-opted and turned into spiffy designer-decorators. Eye candy-pretty variegated surfaces have been applied to both the inside and outside of Frank Gehry’s sleek building sheathed in curving glass façades, situated in the Jardin d’Acclimatation. Like any set of stained glass windows, our perceptions of their surfaces and the colored light they produce changes depending on the time of year and day and the amount of sunlight. Institutional critique, with its now historical status as counter-establishment, is the aloof calling card of the resultant lite light show.

Daniel Buren, “Observatory of Light” (2016), work in situ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (© DB-ADAGP Paris / Iwan Baan / Fondation Louis Vuitton) (click to enlarge)

Buren is known for “examining” how an object or sign is transformed as it traverses physical and conceptual boundaries. As a young conceptual artist, he was considered visually and spatially audacious, objecting to traditional ways of presenting art through the museum-gallery system. In the late 1960s, he connected to deconstructionist philosophies that had as their background the radical May 1968 student demonstrations in France. In Benjamin Buchloh’s 1982 essay “Allegorical Procedures,” he describes Buren’s historical place as revealing the material conditions of ideological institutions. Buren exemplified this hacked space approach in 1971 when he created “Peinture-Sculpture,” a 32-foot-wide, 66-foot-long striped banner hung from the skylight so as to divide the Guggenheim’s rotunda in two, obscuring views of other artworks and the architecture. Dan Flavin and Donald Judd complained that the sculpture blocked views of their work, and the Guggenheim ultimately removed it. For his first New York City solo show, in 1973, Buren suspended a set of 19 black-and-white striped squares of canvas on a cable that ran from one end of the John Weber Gallery to the other, out the window, all the way to a building on the other side of West Broadway, and back. Whenever I am at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris I go see his “Murs de peintures” (1966–77) in the outstanding Matisse room, where its colored, broad stripes, suggestive of the little canvas cabins one sees on Mediterranean beaches, seem very fitting.

Here, with “Observatory of Light,” Buren has masked 3,600 pieces of Gehry’s glassy structure, which rises above the Bois de Boulogne like a ship cresting a wave. The ship is now covered in checkerboard-like translucent colored gels that are punctuated by panes of white stripes, much like his 2005 installation at the Guggenheim, where tinted filters were placed on the skylight over the main atrium. That was very pretty with its unified rose color, but “Observatory of Light” suggests to me the gaudy costume of a court jester and has all the wan and paunchy platitudes I associate with arena rock.

Daniel Buren, “Observatory of Light” (2016), work in situ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (© DB-ADAGP Paris / Iwan Baan / Fondation Louis Vuitton) (click to enlarge)

Buren’s temporary installation art practice supposedly privileges framework over the gaze, stressing references to institutional language and context. The goal is to “question” institutionalization. But at what point in today’s giddy-up art world does the redundancy of Buren’s woozy striped gesture, once used to draw critical attention to a given space or context, itself need to be “questioned” as institutional? Is it still relevant in terms of challenging, thought-provoking art? Can it, with a straight face, still claim to reflect a form of “radical” criticality? (Variations of the word “radical” appear four times in the press kit for “Observatory of Light.”)

Daniel Buren, “White Acrylic Painting on White and Anthracite Gray Striped Cloth” (1966) at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (photo by the author for Hyperallergic) (click to enlarge)

Buren has long been developing an œuvre that is characterized by the rigorous use of a “visual tool” — his 8.7-centimeter-wide alternating white and colored vertical stripes. This tool is best deployed as strong, elegant, minimal paintings that sit on the floor, such as “White Acrylic Painting on White and Anthracite Gray Striped Cloth” (1966). As painting on canvas, this tool has a Duchampian, readymade aspect to it. The strong color stripes on canvas feel good to look at — they are well proportioned — but I can’t recall a single person ever declaring a passion for Buren’s “paintings.” Later, he left painting to delve into architectural applications of the tool and began to deal with the fullness of deep space and highlight art contexts. Buren’s own legacy, perhaps best seen in Felice Varini’s work, seems to be in situ art conceived specifically for a space (a context) that is provided by the host venue. No longer a divisive perimeter figure, but an insider of the French art establishment, his turn to transforming venues with color, as here, makes for feel-good projects that “everyone” “should” “love.”

Daniel Buren, “Observatory of Light” (2016), work in situ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (© DB-ADAGP Paris / Iwan Baan / Fondation Louis Vuitton)

It was consistently gray in Paris this spring, and the day I went to see “Observatory of Light” it remained so. Very little color warmed the inside surfaces of the building. The structure just sat there in its new patterned robe, as if waiting to be asked to dance. I enjoyed this supercharged circus tent, even as I found its blithe peppiness meaningless — never challenging, offending, disturbing, or polyvalent. Buren’s defanged Duchampian style, missing in high-noon shine or larky brashness, has a primping and riffing aesthetic of high-handedness that left me cool. The work has terminal whimsy, like some farcical, bored, old burlesque act.

In 1966 and 1967, Buren joined forces with fellow artists Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, and Niele Toroni to form the group BMPT, whose intention was to reduce paintings to the most basic physical and visual elements through the systematic repetition of motifs. Later, Buren collaborated with Hermès on several occasions, including for the creation of luxury scarves. Perhaps this Hermès connection is unsurprising in a time when bohemian hipsters pretty much define the new bourgeoisie, but I still find it a contradictory proposition when the word “radical” is being tossed around in descriptions of the artist’s work. How could a cultish conceptual artist, an art historical institution in his own right now working for a luxury brand, still pretend to critique the institutions of art?

Daniel Buren, “Observatory of Light” (2016), work in situ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (© DB-ADAGP Paris / Iwan Baan / Fondation Louis Vuitton)

Or is this radical chic question one that should no longer be asked? Some might say thatof course all art has been reduced to entertainment and cynical investment commodities; to expect or fight for more is sheer folly. In his Theory of the Avant-Garde (1984), Peter Buerger explained that the historical avant-garde movements, and the social subsystem that was art, had entered a stage of ironic self-criticism and defeat. Still some, like Colab, rejected that sweeping premise. It was obvious that, as Buren put it in his 1970 essay “The Function of the Museum,” that the museum imposes its frame on everything that is exhibited in it, in a deep and indelible way, because “everything that the Museum shows is only considered and produced in view of being set in it.” This, in essence, is the lesson of Duchamp’s urinal. In his 1971 essay, “The Function of the Studio,” Buren argued that an “analysis of the art system must inevitably be carried on” by investigating both the studio and the museum as the “ossifying customs of art.” Indeed. Buren’s current sybaritic in situ art, with its stated goal of exposing institutionalization, is a central candidate for such exposure. It is superficial spectacular art for a superficial spectacular art world with a propensity to dazzle.

Unless one falls into a deterministic notion that all art is forever destined to be a luxury good — and we are unable to imagine and construct another communicative role for art — we should take seriously the challenge to cultural reification that Buren’s anachronistic interventions once posed. Such a pushing back at the current 1% power structure in art may require a post-conceptual art that has absorbed the tropes of previous conceptual attempts at resistance and surpassed them. Otherwise, any attempt to see the artist as a moral social critic of the corporate gods vanishes into pure, spacey, pretty, ice cream colors (in service to those corporate powers). “Observatory of Light” is conceptualism without irritation, where nuanced contextual ideas have been turned into a forlorn formula for slick, high-end décor. It is also a place to observe the failure of Buren’s ingenious contextual radicalism. A place to observe how what made him famous has devolved into a shiny entertainment platform, suitable for suburban family cultural life.

Daniel Buren, “Observatory of Light” (2016) seen in overhead photo of Fondation Louis Vuitton (© Phillipe Guignard / Air Images / Fondation Louis Vuitton)

Daniel Buren’s installation “Observatory of Light” is on long-term view at the Fondation Louis Vuitton (8 Avenue du Mahatma Gandhi, Bois de Boulogne, 16th Arrondissement, Paris).

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario