How to modernize your medium.

Installation view of Music is a s-s-s-serious thing at 303 Gallery, New York. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Installation view of Music is a s-s-s-serious thing at 303 Gallery, New York. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Carron was kind enough to give me a tour of his recent exhibition at 303 Gallery in New York, Music is a s-s-s-serious thing. The title borrows the words of the Romanian pianist Dinu Lipatti who, despite a very short career, was considered one of the most talented musicians of the 20th century. Carron’s first source of inspiration for this exhibition was an LP recorded by the pianist, which features abstract graphic design on the cover, though he eventually parted from any visual reference to it. Much like the sculptures he appropriates, Carron altered the quote with a stammer. A repetition of the consonant S, which alleviates the seriousness conveyed by Lipatti’s words.

The exhibition juxtaposes reproductions of men’s belts indolently positioned on found cabinets and stools and a series of paintings on tarp initiated in 2006. Made of glass and individually molded and pigmented, the sculptures were fabricated in collaboration with the Kunstbetrieb in Basel. They evoke the lassitude of a worker coming home after a hard day’s labor, nonchalantly taking off his belt. The paintings reproduce book covers from the early 1950s to the mid-60s. The found motifs are painted on tarp which is then stretched on plumbing pipes in a gesture the artist calls “a pathetic attempt at modernizing painting.”

I discovered Carron’s works through his attempts at deconstructing Swiss mythologies by creating resin casts of visible beams from a Swiss chalet. Which is telling of Carron’s thinking and work process, continuously contemplating a vast range of questions regarding the formulation of identity: How does a collective national narrative form? How does one become an artist? Echoing Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If,” Carron humbly asks, How does one become a Man?

When I ask him about the shadow of melancholia cast by his works, Carron confesses his fascination with sentimentalism. He is exploring ways to represent such feelings beyond the realm of his own emotions. His approach is somewhat Warholian as he perceptively explores these concepts while remaining on their surface, where ultimately the truth lies.

Valentin Carron Three or four years ago, I took a picture of my drooping belt on a chair for someone who asked me about the brand. I found the image pathetic, and I knew I wanted to reproduce that scene.

Clément Delépine I see a continuation with the snakes that you had defined as “a gaze into suspension.” Can the belts be considered a creeping threat?

VC Yes, absolutely. There’s an aesthetic continuity. I was also thinking about the concept of the figure, and a certain weariness that is inherent in the reclining nude in which the furniture serves as base.

The supporting furnishings are essentially those of squatted houses, things that I got at Emmaüs, the French equivalent of the Salvation Army. The starting point came as I thought about showing in New York as an opportunity to start a discussion with the American public. In preparation, I tried to examine banal examples of American design.

It's kitsch furniture, from seedy dive bars. I wanted to put this furniture in contrast with high-end craftsmanship, objects that require complex processes to fabricate.

I think that modernity was built on these solitary heroes. I'm a fan of the television show Les ingénieurs de l'impossible (“The engineers of the impossible”), which explores how infrastructural devices are made. This furniture in my exhibition directly relates to the imagined furniture of the workers who produced these complex objects.

CD There is a fascination with the concept of the beautiful loser.

Belt on valet stand, 2014. Plastic, metal, glass, paint, 47 x 18 1/2 x 12 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Belt on valet stand, 2014. Plastic, metal, glass, paint, 47 x 18 1/2 x 12 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

VC Absolutely, I have the feeling that my culture, from the start, operates around this figure. In a way, it reflects a musical culture. The French singer Renaud, who I think was a precursor of grunge, was singing Je suis une bande de jeunes (“I am a gang of youths”). As in, I am a gang of youths all by myself. In the music of Renaud, there was a feeling of collectivity. Belonging to a culture is also a way to feel less alone.

CD It's all related to your interest in how to reflect the great narratives of national identity. Your work results in a reproduction of typical architectural elements, dematerialized then recast with lighter materials to in an attempt to only retain their connotative meaning.

VC Absolutely, and their shape, since I was positioning them in space to imbue the objects an authoritarian quality.

CD But those belts are ultimate symbols of authority.

VC Yes, absolutely, it is potentially a weapon, a device for submission. But this authority is disabled here—doubly disabled. By its form and placement, and also by the object’s material. As with previous sculptures that I appropriated, I copied them while deactivating them.

CD So do you make them harmless?

VC I don't think so. I make them lighter. These sculptures are often set in public spaces and I use them as images. I lighten the sculpture, I move it, prompting a paradigmatic shift.

CD How did you conceive this exhibition?

VC Originally, I only wanted to have only one piece, just to accentuate the drama. But I ultimately wanted to break my own habits. Usually I play a scenario, a story. By multiplying the possibilities, I multiply the opportunities, the belt twists, the staging.

Belt on braided chair, 2014. Plastic, metal, glass, paint, 28 3/4 x 19 1/2 x 22 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Belt on braided chair, 2014. Plastic, metal, glass, paint, 28 3/4 x 19 1/2 x 22 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

CD You have a real respect for craftsmanship. Even when you dematerialize the pieces, altering the viewer’s sense of material by casting it in a lighter matter, you are reasserting an artisanal process.

VC Yes I cannot deny it. But it is an extremely cumbersome process when compared to the ease of the object's discovery. For most of the works, two pieces of furniture were purchased: one as a support for the belt in the initial molding process and a duplicate on which I placed the molded belt. To build the mold, they reproduced the furniture identically, otherwise the trace of the mold would have shown on the presented piece. I also asked that the buckles, the metallic parts, be painted to resemble the originals. The colors are all different, some are warmer, some colder, some silvery. It's pretty specific. I didn't want to make the perfect object. I had to sabotage it a little. I degrade the process. Not focusing too much on the technicalities, altering like that, while trying to do it well. I wanted to make it more Pop and less an experiment made out of glass.

This prompted a number of issues since the color, the transparency of glass depends a bit on the complexity of the molding. Some glasses are more opaque or transparent because they would solidify before the pigments could reach all parts of the object. The choice of color is a bit dictated by choice of shape.

CD You started the series of paintings on tarp in 2006.

VC Fundamentally, I've always been a painter.

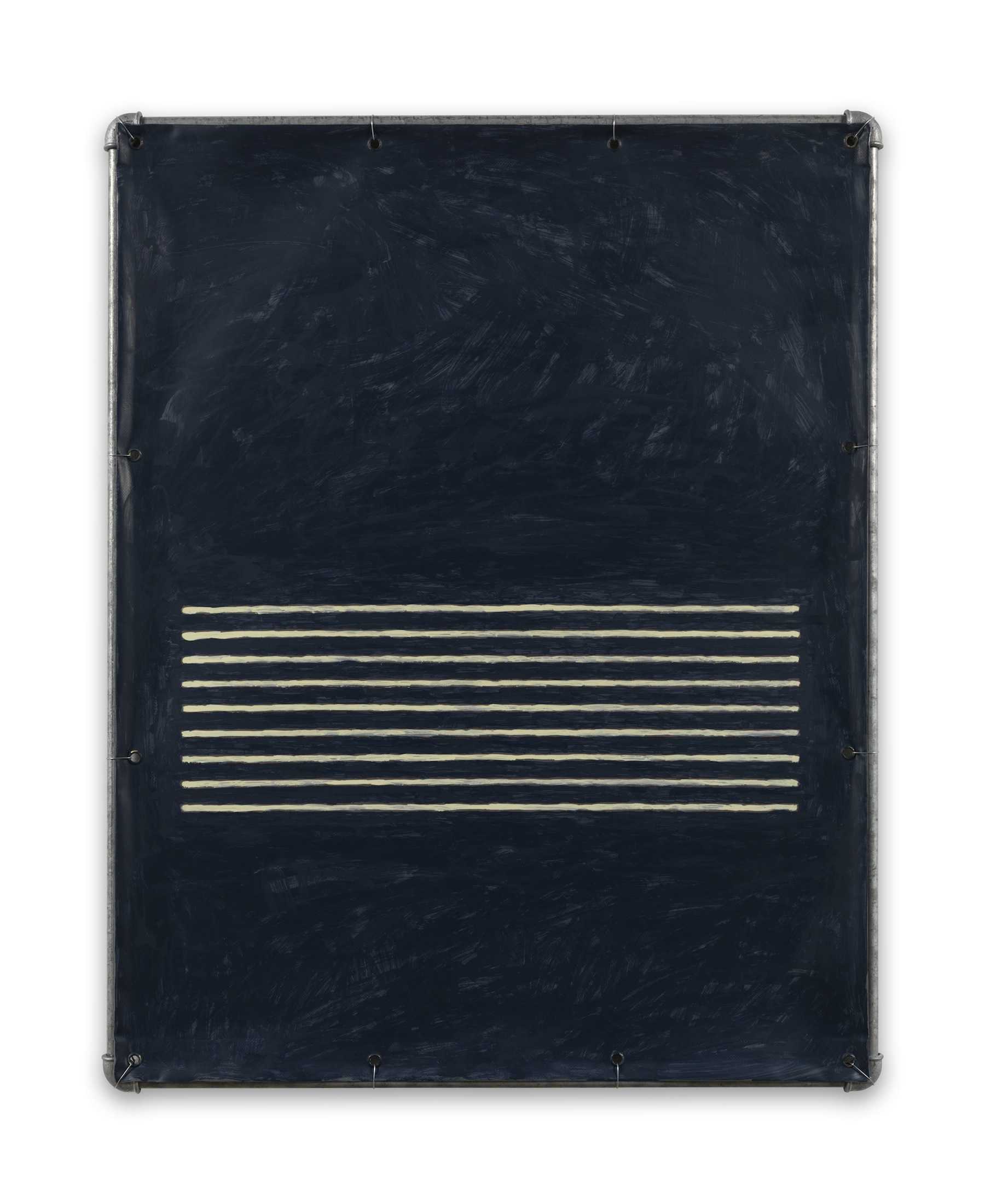

Jazz, 2014. Vinyl ink on pvc tarpaulin, galvanized steel tubing, and metal wire,

38 1/2 x 30 1/2 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Jazz, 2014. Vinyl ink on pvc tarpaulin, galvanized steel tubing, and metal wire,

38 1/2 x 30 1/2 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

CD Do you consider painting to be the medium par excellence?

VC It was, in any case when I started it was. I attended a very regional school. I became interested in art in the early ’90s. In ’92 or ’93 maybe, I went into a library where I searched what painting was. What painting of the 19th century is, modern, contemporary. One of the first movements that touched me was the Italian Transavantgarde: Enzo Cucchi, Francesco Clemente. It was a Gerard Garouste period too. Unfortunately or fortunately. I have been painting since the beginning. I’ve taken it in many different directions, even self portraits

CD You showed only paintings earlier this year at the Kunsthalle Bern. Originally, the motifs all derived from book covers.

VC I'll confess that I have always tried to avoid painting. When I see the result, I understand why (laughter).

There is quite a protocol related to these paintings for me. There is the topic of research. Initially I was going to source the books from second-hand bookstores. Mostly hardcovers from the ’50s and ’60s. These are not luxury items. What really interests me in the end is the subject shown on the cover, not the book itself. The question I want to explore is, How is a novel synthesized and illustrated? At the same time there is something gratuitous in these representations. First comes the discovery of the subject. I go to online shopping sites; I enter some search criteria like “modern library,” “postwar,” “45–65,” “with picture,” or “hardcover”; and the results are displayed. Then, I frantically order books according to their visual composition, and go from there.

CD Your paintings often have very poetic titles, while the titles of your sculptures act as descriptors.

VC Yes.

CD I was wondering if with painting you are already in the allegory, while the sculpture stays in the commentary.

VC My sculptures are also concerned with the allegory. It is specifically for this new series that I wanted to stay in the commentary. The titles are very descriptive of what happens. I wanted a rather cold and clinical description. On the other hand it is true that I use these titles for paintings too—well, sometimes I do and sometimes not because I want to give myself total freedom.

In painting, I want to challenge myself. I envisioned a kind of grand modern painting. A painting that could have been done in the ’60s. But all this ambition is upended by the fact that this painting is done this way.

For me, the basic protocol, since we spoke before of the beautiful loser, is a pathetic desire to modernize the painting medium. To want to make it evolve.

CD To paint you need to develop a new medium?

VC Yes, this may be why we possibly cannot talk about painting but painted objects, even a paint object. It is a willingness to challenge the idea of painting. I paint, which is traditional. But I want to modernize it by employing industrial materials.

CD It is traditional and desacralized. It's a painting on a tarp stretched with wires on a frame made of plumbing parts.

VC Yes. Modernized in the sense of the use of materials. The canvas is a canvas already waxed. Then the process devolves and becomes very reductive. I copy details. I love it.

CD In a previous interview with Fabrice Stroun, you said you spare no efforts to make it not too bad, not too good.

VC Absolutely. It is very demanding. Knowing that normally when you make a painting, you make a first layer and then put your lines on top. Somehow, I am subjected to the drawing, to the pattern. I use an overhead projector, I trace the outline and then paint. But there is no hierarchy between the background and the subject.

CD There is no perspective, everything is in the foreground?

VC These are issues that also interested me in painting. These are very common questions, but I wanted to explore it through this digression.

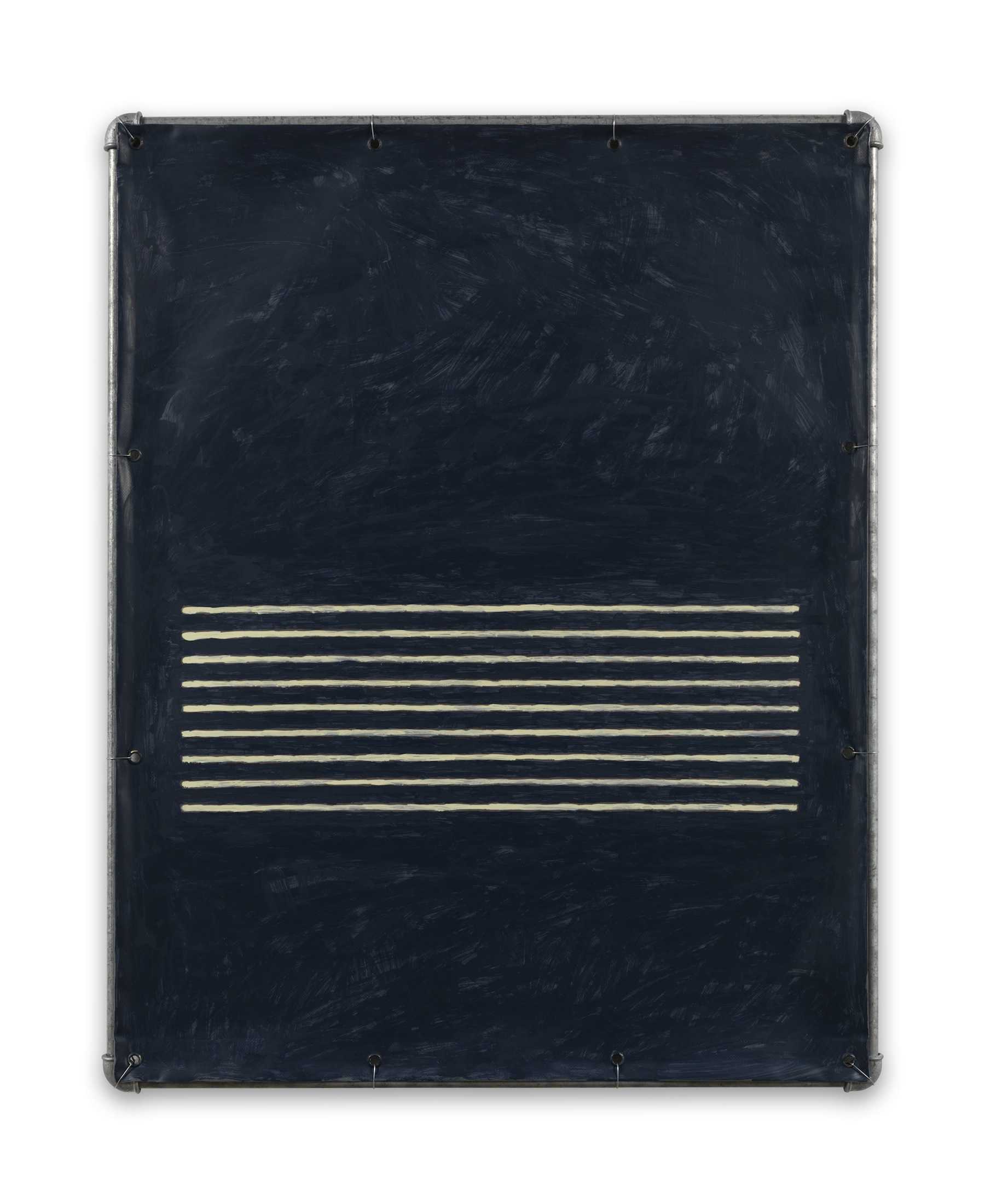

Lamento in blue bianco, 2014. Vinyl ink on pvc tarpaulin, galvanized steel tubing, and metal wire, 38 1/2 x 30 3/4 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

Lamento in blue bianco, 2014. Vinyl ink on pvc tarpaulin, galvanized steel tubing, and metal wire, 38 1/2 x 30 3/4 in. © Valentin Carron, courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

CD Is it a way of criticizing art history? In that it defines what is art and what is not?

VC There is this notion, this labor, at the same time this cowardice. And at the same time there is re-composition. I then fall into the painter's work in a very classical sense. I have my subject, my book cover. How do I reproduce it? Which frame, how big? At what scale, how do I compose? Do I stay as close as possible to the original colors or do try something? I also wish to only make one layer. I don't touch it afterward.

CD You do not do sketch beforehand or correct afterward?

VC Sketches yes, with the overhead projector, which gives me the drawing, and then I keep it as simple as possible. There is no remorse. I will not try to add another layer of paint. And then there is the title, which is the thing I prefer the most.

For these paintings I have the feeling I'm going back to reclaim and reimagine some 20th-century painting. I really see in it a painting of the ’50s, quite radical for the time. But it is an act, I get into a role when I paint like that.

CD Do you recall the movie, Et la tendresse?... Bordel!? There is a scene where Jean-Luc Bideau tells his son that he will be a man the day he can jump in with both feet in his underwear. And I feel that’s what you get confronted with a little, that painting is jumping with both feet into your pants...

VC Yes. I remember the first time I made a monochrome, in art school. I was seventeen or eighteen years old. I stretched it, already with vinyl…leatherette actually. I made a dripped monochrome with enamel paint, classic. And I remember that a teacher had called me and asked how I had come to the monochrome. He said, “not everyone can paint a monochrome.” I don’t have to justify that. I just hop on the train. Relevance is in the making.

Clément Delépine is Assistant Curator at the Swiss Institute, New York.