KOCHI, India — I could start with clichés, as many do when writing about Kerala, the southernmost state of India, which tourism officials have dubbed “God’s own country.” But I will note, instead, the dangerous road manners I encountered en route from a picturesque village in northeast Kerala to Ernakulam, the state’s modern metropolis, home to malls and metro lines, and host, on the island of Fort Kochi, to India’s first art biennial. Travelers and merchants have followed ancient routes to arrive on the island’s shores for millennia now. The latest reason to set sail is the Kochi-Muziris Biennale(KMB), currently in its third edition.

Founded by artists Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu in 2010, and named partly after the lost port of Muziris — which is believed to have been the region’s hub of trade before its disappearance — KMB is always curated by artists. This distinctive tradition will likely come under closer scrutiny in light of the Biennale’s current outing, which is sorely unable to match the ambitions of its curator, the artist Sudarshan Shetty.

The curatorial theme of the current Biennale, Forming in the pupil of the eye, is derived from an old story about a young traveler who seeks a meeting with a wise sage to try to understand the complicated multiplicities of all that is. “[G]athering the world into the pupil of her eye,” Shetty writes in his curatorial note, “the sage creates multiple understandings of the world.” Accordingly, he writes, the Biennale is “an assembly and layering of multiple realities.” What that translates to, in the picturesque lanes of Fort Kochi and its many gorgeous venues, is a mishmash of works derived from multiple disciplines that somehow all stand in isolation, never coming together to form anything coherent.

The list of participating artists for the current KMB features an unusual and intriguing array of poets, musicians, dancers, and contemporary artists from 35 countries. When it was first released, I had eagerly anticipated discovering what such a gathering of artists might look like in rooms and hallways forever imbued (in my mind at least) with the aroma of the spice bags that must have passed through them. Now, several weeks after my visit to the current KMB, it is already hard to jog any individual work from memory and feel pleased to have seen it.

My first stop is Aspinwall House, the Bienniale’s main venue and the former headquarters of Aspinwall & Co Ltd. — a company established in 1867 that traded in in coconut oil, pepper, spices, coffee, rubber, and other goods. I soon find myself walking in and out of the rooms swiftly, with little to hold my attention.

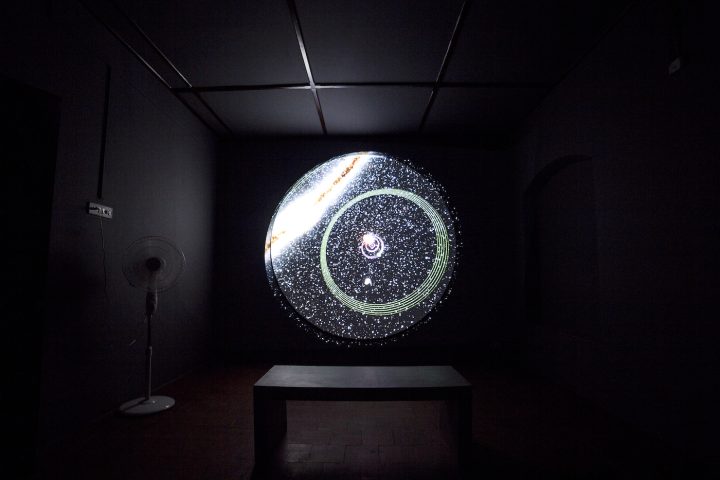

Across the Bienniale’s lovely venues, there are several works that, when seen in isolation, are either thought-provoking, entertaining, engaging, or all of the above. Among the most memorable are the Russian collective AES+F’s sleek and silly three-channel video work “Inverso Mundus” (2015); Alicja Kwade’s intriguing concrete wall and mirror installation “Out of Ousia” (2016), which plays with perceptions of what is original and what is a replica; and Padmini Chettur’s video installation “Varnam” (2016), which explores the nostalgic remains of eroticism and romantic love — the term “varnam” referring to the central section in a classical Bharatanatyam dance performance.

My disappointment springs not so much from any individual work, but how they all feel when experienced together. The rooms frequently strewn with remnants of performances feel like I am arriving at a party after everyone has left for the night, while other installations feel like pages torn away from precious books to paste on the walls. The sentiment behind trying to preserve and document these ephemeral acts is appreciated, but it is really a case of trying too hard to please, and failing.

After treading in and out of several KMB venues, I arrive in a sparsely lit room where the Latvian artist Voldemārs Johansons’s “Thirst” (2015) is showing. A video of a stormy North Atlantic Ocean filmed in the Faroe Islands, the work is a single-shot visual capturing the sea in all its fury. Coupled with the waves’ frightening roars, the video truly envelops the visitor; it is threatening and immersive, drawing you in, spitting you out, relentlessly pulling and pushing. It is a powerful experience and I know my memory of it will endure. The anger in the piece and its strange beauty mingle with the sentiments I have developed for the Biennale as a whole and the haunting allure of its venues, most of which are only accessible to the public during KMB’s three-month run. Being alone in these gorgeous buildings, standing in their upper rooms and watching the ships go by in the near distance, hearing the waters churning, and smelling the spaces’ evocative aromas, makes me glad that I am here. In these moments, the Biennale recedes.

Between a dozen main exhibition spaces, several smaller venues, collateral events, and the Student Biennale, there is much to see at KMB. As I make my way around Fort Kochi, I find myself looking up at the tall roofs and watching out from the expansive docks at the rear of the buildings instead of into the rooms and at the works. Nothing seems to fit anywhere.

Later — much later — my companions and I are sitting around a table over cold beer and a passable dinner, dissecting the day. It is a very pleasant evening in late January. There is a tiny pool near our table, and a Christmas tree made with sticks and lights that is much prettier than my description makes it sound. The conversation goes round and round, and the question that arises is: can language be visual art? There is no reason why it cannot be, but it certainly isn’t at KMB. The distance from one work to the next, from one venue to another, is the time the viewer has to process and ruminate on each experience. In this interim space between viewing each work, it’s the responsibility of the curatorial theme to facilitate a sense of continuity, a sense of coherence between otherwise disparate works.

Shetty took a gamble when he sought to bring other creative disciplines into the Biennale’s visual context. Did it pay off? Unfortunately, no. The latest edition of KMB is a brave experiment that doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. But going to Fort Kochi — with its streets as old as time, its fabulous buildings and warehouses, and the river that runs through it — remains a grand aesthetic experience.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario