lunes, 27 de febrero de 2017

DOCUMENTA 14 (2017)

- CREADORES

- Daniel García Andujar

- Mattin Artiach

- Roger Bernat

- Niño de Elche

- ORGANIZADO POR

- documenta

- CON LA COLABORACIÓN DE

- Acción Cultural Española (AC/E)

La exposición Documenta es una de las mayores muestras de arte contemporáneo del mundo que se celebra desde 1955 cada cinco años en la ciudad alemana de Kassel y dura 100 días. Por primera vez en su historia, Documenta se celebra en dos sedes, la segunda es Atenas bajo el título Documenta 14: Aprender de Atenas.

Esta decimocuarta edición comienza en abril de 2017 en Atenas y luego se inaugura el 10 de junio en Kassel. De esta manera coinciden, de manera paralela, un mes en ambas ciudades. La co-organización de la 14ª edición de Documenta entre Kassel y Atenas es una propuesta de Adam Szymczyk, director artístico de la feria, quien explicó que el propósito de dicha decisión es «reflejar la situación actual en Europa y poner de relieve las tensiones palpables entre el norte y el sur». Szymczyk considera que la elección de Grecia se desmarca de los conflictos entre el país mediterráneo y Alemania y que su punto focal es su situación geográfica y la migración. «Lo que me interesa de Atenas es que se trata de una metrópolis que se conecta con otras a través del mar. Limita con Turquía, tiene una gran afluencia de inmigrantes procedentes de Asia y África. Atenas es un portal o una frontera a la que llega mucha gente que puede tener visibilidad », dijo Szymczyk.

Con esta iniciativa Documenta abandona por un año su papel de permanente anfitriona para convertise en invitada de Atenas. La dirección artística está a cargo de la comisaria y escritora Marina Fokidis, fundadora y directora artística de Kunsthalle Athena. En esta edición el director artístico de Documenta, Adam Szymczyk ha invitado a un grupo de artistas españoles a participar con el apoyo de AC/E: Daniel García Andujar, Mattín Artiach, Roger Bernat y el colectivo “El Niño de Elche” formado por Israel Galván, Pedro José González Romero y Francisco Molina.

- See more at: http://www.accioncultural.es/es/documenta_14_2017#sthash.YCokaUeY.dpufEsta decimocuarta edición comienza en abril de 2017 en Atenas y luego se inaugura el 10 de junio en Kassel. De esta manera coinciden, de manera paralela, un mes en ambas ciudades. La co-organización de la 14ª edición de Documenta entre Kassel y Atenas es una propuesta de Adam Szymczyk, director artístico de la feria, quien explicó que el propósito de dicha decisión es «reflejar la situación actual en Europa y poner de relieve las tensiones palpables entre el norte y el sur». Szymczyk considera que la elección de Grecia se desmarca de los conflictos entre el país mediterráneo y Alemania y que su punto focal es su situación geográfica y la migración. «Lo que me interesa de Atenas es que se trata de una metrópolis que se conecta con otras a través del mar. Limita con Turquía, tiene una gran afluencia de inmigrantes procedentes de Asia y África. Atenas es un portal o una frontera a la que llega mucha gente que puede tener visibilidad », dijo Szymczyk.

Con esta iniciativa Documenta abandona por un año su papel de permanente anfitriona para convertise en invitada de Atenas. La dirección artística está a cargo de la comisaria y escritora Marina Fokidis, fundadora y directora artística de Kunsthalle Athena. En esta edición el director artístico de Documenta, Adam Szymczyk ha invitado a un grupo de artistas españoles a participar con el apoyo de AC/E: Daniel García Andujar, Mattín Artiach, Roger Bernat y el colectivo “El Niño de Elche” formado por Israel Galván, Pedro José González Romero y Francisco Molina.

sábado, 25 de febrero de 2017

jueves, 23 de febrero de 2017

ARCO 2017: Ian Waelder, el artista skater más precoz de la feria que cotiza al alza

La obra de Ian Waelder, con 23 años el más precoz en ARCO, está influida por el "skateboard" y se cotiza al alza. Algunas piezas rondan los 5.000 euros.

"I used these shoes for a few months" (Usé estos zapatos durante pocos meses) es el título de la obra que el artista Ian Waelder (Madrid, 31 de marzo de 1993) presenta en el stand de la galería L21, y haría las delicias de Marcel Duchamp. "Estar en ARCO en un momento tan temprano de mi carrera es una oportunidad para situarme en un buen contexto profesional y una muestra de confianza hacia mi trabajo", responde a Fuera de Serie. Esta escultura de bronce de dos piezas unidas con cordones de zapato negros, colgará estos días del techo de la feria de ferias, la más importante de arte del país.

Nacido en Madrid, está afincado en Mallorca. Su trabajo se exhibe en la galería L21.

Con bastante seguridad, Ian es el artista más joven de esta edición de ARCO Madrid y una excepción en la edad media de quienes se presentan en Ifema. A sus 23 años, Waelder, de madre estadounidense y padre chileno, nació en Madrid pero se crió en Mallorca, donde explica cómo la actividad del skateboard le ha hecho tomar consciencia de aspectos de su trabajo como artista. "Esa degradación de las cosas, de los materiales o del cuerpo... Quizá interesarme por el espacio de otro modo. El skate es un ambiente en el que se junta gente muy creativa, en relación con el cine, la fotografía y la música", detalla.

A finales de 2016 mostró sus creaciones en el nuevo espacio de su galería mallorquina, en el Polígono de Son Castelló, trabajos de mayor calibre, después de sus residencias en Hangar Lisboa (2016) y NauEstruch, Sabadell (2015). Ganador de la beca INJUVE2015 , premiado con el SCAN de fotografía de Tarragona 2014, mención de honor en Ciutat de Palma (2013), entre otros méritos, es autodidacta. Su trabajo explora, en sus propias palabras, "la cultura suburbana a través de la memoria", usando como formatos "la fotografía, el sonido o la escultura".

El trabajo del artista madrileño explora la cultura suburbana a través de formatos como la fotografía, el sonido o la escultura.

Con una madurez sorprendente, explica cómo un buen resumen de su trabajo sería la frase del artista francés Raphaël Zarka: "El ruido, las marcas y rastros son el resultado de una actividad que no necesariamente esperaba producirlos. Parte de mi trabajo se nutre de mi experiencia en el mundo del monopatín y su cultura. Estoy interesado en esos rastros generados por el individuo de forma azarosa y recogiendo diferentes experiencias de las que me rodeo".

Obra de otro de sus trabajos, la serie 'White Folds' (2.500 euros)

'I used these shoes for a few months' fue ideada en 2015 y forma parte de una serie en la que Waelder guarda zapatos a medida. "En su mayoría están desgastados a causa de su uso para la práctica del monopatín, lo que genera una serie de marcas en unas zonas muy concretas que alguien experimentado en el tema puede identificar con una serie de movimientos y tiempos aproximados de uso", afirma. "Las fundo en bronce con una pátina negra, congelando esos desgastes, e indicando en cada título el tiempo en que fueron utilizados".

Otro de sus trabajos, la serie 'White Folds' (2.500 euros), surgió casi por accidente: "Son las fotos impresas en gran formato que iba descartando de una serie anterior que consiste en fotos plegadas para caber en el interior de un sobre y mandarlas por correo postal al lugar de exposición; eran usadas en su cara posterior para probar los sprays negros que tenía en el estudio. Al ir viendo esos trazos, comencé a fotografiarlos e imprimirlos; se trataba de darles valor y conservarlos para siempre ".

miércoles, 22 de febrero de 2017

From Seminal Fluid to Sassy Scribbles: The “Non-Art” Works of Marcel Duchamp

While his readymades are a triumph of pure indifference over taste, admirers of Marcel Duchamp continue to be far from indifferent to this cryptic artist. By offering more than homage, Elena Filipovic’s The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp, a fascinating and unique new archival-based book on Duchampian ephemera, surpasses the mere addition of hagiographic detail. Illuminating Duchamp’s often accomplished (if subtle) exploits, the book also offers a glimpse into the tension between art as theoretical inquiry and art as institution (what philosophers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer called the culture industry) by unveiling an eclectic and brilliant range of Duchamp’s innocuous, fragile, and fleeting projects. This is achieved through a richly illustrated and meticulously researched consideration of the fugitive art actions performed by the audacious person named Marcel: his window displays, art dealing, designing of surrealist shows and catalogues, promotional activities, administrative functions, and ambivalent curatorial personae, for example. Yet happily, even after digesting this considerable amount of ostensibly transitory disclosure, Duchamp remains an unadulterated, irreverent enigma — only a much deeper one.

I expect this archival deep dive to reanimate interest in the multidimensionality of Duchamp by focusing our attention not so much on his admirable paintings (something well achieved at the momentous Centre Pompidou exhibition Marcel Duchamp. La peinture, même) or his readymades or installations, as on his “non-art” works: stressing the systematic ephemerality of Duchamp’s acts of reproduction, repetition, and the Rrose Sélavy transvestism he adopted. As such, the book takes us far from the clichéd, trite, conventional (ab)use that some successful postmodern appropriation artists have made of Duchamp by merely aping the enigmatic genius by which art objects were created entirely through the singular whim and arbitrariness of his psyche. No, I would go so far as to say that the considerations here of Duchamp as an impudent but fragile, complex human radically extends the conventional Dada consciousness that always hovers over him.

This is achieved through the author’s devotion to the man and the role his art plays within society. By drilling down into the minutia of Duchamp’s role(s) as administrator, archivist, art advisor, curator, publicist, reproduction maker, and marketing art salesman, Filipovic (the current director and chief curator of the Kunsthalle Basel) manages to both contradict and deepen Duchamp’s indispensable dandyism, transferring his general bohemian ideals from attitude into work. Indeed, we discover that Duchamp’s nonchalance did not exclude intense rigor.

Drawing on many rarely seen images, Filipovic traces the lines of a new Duchamp, someone somewhat removed from the objects he produced. She begins her book, the product of 15 years of research, writing, and exhibition-making, in 1913 — skipping over the artist’s major mechanomorphic works of technological awareness from 1912 — when Duchamp started producing his extraordinary cyborg paintings that depict mechanized sex, such as “Le Passage de la Vierge à la Mariée” (1912) and “La Mariée” (1912). Both these works clairvoyantly interface bodies with stuttering machine forms in the interest of suggesting the obfuscated artificial life of sex-machines and their lascivious caprices.

After a short approbation of the obscure and unorthodox “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 3)” (1916) — Duchamp’s painted photograph of his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2)” (1912) — Filipovic unspools a resounding consideration of the artist’s even more obscure activities of note, including writing, archiving, and photographing related to the readymades and “La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même” aka “The Large Glass” (1915–23), the work André Breton called Duchamp’s anti-chef d’œuvre (anti-masterpiece). This includes the box of notes known as “La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (Boîte verte)” (1934) and the melancholic museological project known as “Boîte-en-valise (de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy)” (1935–41). The boîte is a miniature museum archival work that managed exacting toy replications of Duchamp’s own works: a project aiming to create interplaying relationships between his artworks and the audience. For it, Duchamp had texts, images, and miniature objects manufactured with such crazy fidelity that there was often more work involved in making the tiny copy than the original.

Next, the book reproduces the odd and strikingly juicy piece unique“Paysage Fautif” (1946) from the Museum of Modern Art in Toyama, Japan, which consists of seminal fluid on black satin. It was included in a deluxe edition of “Box in a Valise” (1935–41) that Duchamp gave to the Brazilian artist Maria Martins, his lover and the body model for the nude figure in “Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’éclairage” (1946–66). Their love affair started in 1946 and lasted for several years, ending with her departure for Brazil and with Duchamp’s 1954 marriage to Alexina “Teeny” Duchamp. A genetic test in 1989 confirmed that the semen in this piece is indeed that of Marcel Duchamp. The other libidinal piece unique was made for the Chilean artist Roberto Matta out of human head, armpit, and pubic hair and one sensual and delicate contour line by Duchamp in 1946 called “Untitled.”

One of the lovelier examples provided is the much earlier “The Box of 1914” (1913–14), a commercial cardboard photographic supply box that (in an edition of five) contains photographic facsimiles of 16 pithy manuscript notes and two images: “Avoir l’apprenti dans le soleil” (1914) and “Médiocrité” (1911). With great sass, Duchamp photographed his funky hand-jotted notes on torn scrap paper, making documents of documents and inventing the photocopy machine avant la lettre. This slew of photo facsimiles was tossed docilely into the box(es) with no linier order prescribed. Also included were images and notes for the crucial “3 stoppages étalon” (1913–14), a key work in the development of the artist. For Duchamp, the chance-based aspect of this work and “The Box of 1914” opened a conceptual (before Conceptualism) way to escape traditional methods of expression long associated with high art.

The second chapter explores Duchamp’s curatorial strategies, his art dealing, and his fascination with reproducing (his) art and the publicity that goes with art promotion — in other words, the distributive apparatus of art within society in his time. Key is the ensnarling installation “Sixteen Miles of String” (1942), in which Duchamp presented The First Papers of Surrealism exhibition at the Whitelaw Reid Mansion in Midtown Manhattan. By creating an immersive web throughout the space with string, he deliberately frustrated easy perception of the paintings on view, using the obscuring mesh to create frustration and thereby enhance desire. (There is a dashing photo by Arnold Newman of Duchamp himself embedded in this netting.) Other visual highlights in this meaty section include four photographs of Duchamp’s dumpy New York studio casually strewn with readymades around 1917, a photograph of the installation he created in 1933 of Brâncuși’s sculptures at Brummer Gallery in New York (where he trimmed down “Endless Column,” 1918, a bit so as to fit it upright in the space), and two papier-mâché models of the urinal piece “Fountain” (1938) for the limited edition “Boîte-en-valise.”

Filipovic’s stylish consideration of “Boîte-en-valise” is particularly admirable, teasing out how its simulacrum of the social function of the art museum transforms the primary language of art into the secondary language of culture. With “Boîte-en-valise,” presumptions of preservation from decay and social valorization through extraction from social context and function are (with hubris and prescience) self-performed. What we have here is a self-curated retrospective of self-citation, created at a time when Duchamp was barely recognized and poorly appreciated. (Meanwhile, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse had just been fervently hailed as the reigning modern art masters with their first Parisian retrospectives and with Christian Zervos’s lush catalogues raisonnés published by Les Cahiers d’Art.) Boldly, precipitously, and preposterously, Duchamp’s fastidious self-glorifying work brilliantly performed a double act of succinct self-presentation and disembodied negation through his choice of timorous miniaturization matched with the multiplicity inherent in its shipping-ready form: tiny reproductions boxed for wide distribution. This self-negating deluxe museum-as-archive acted as a new form of art (what we now call book art) by forgoing the scale and presence endemic to the grandiose museum context and its autocratic clout.

The third section, which ends the book in 1969, focuses in on Duchamp’s replicating procedure concerning administrative efforts and his clandestine maneuverings to complete and posthumously embed Étant donnés into the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Curious thematic and formal precedents are established between it and Duchamp’s conceptualization of the exhibition design as grotto for the Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme (EROS) held in 1959 at Gallery Cordier in Paris. But the best images in the book are of Duchamp’s black workbook Manual of Instructions, which contains detailed installation specifics for Étant donnés, including sketches, his own photography, and instructions (penned in his beautiful handwriting) set out on pale cream, dusty pink, and green pages. These plates, full of poetic elusiveness, illuminate the push/pull of Duchamp’s exquisite dilemma: his obsessive devotion to detail in placing his work in the museum and his longstanding retinal trepidation concerning the scopic regime inherent in all art museums. The spread-open double pages of Manual of Instructions are riveting and full of trepidation. Indeed, this body of work contains some of Duchamp’s creepiest, harshest, and most bizarre single images, such as the signed figure for Etant donnés, when still installed in Duchamp’s East 11th Street studio in 1968, and the loose 1959 photograph with red crayon markings of the cast-plaster female figure that came to dominate the finished Étant donnés installation.

All told, this well-written, well-produced, image-heavy book does a skillful job of conveying the way Duchamp’s sexual passions were tied to his marginal but reoccurring art-related activities. The interesting part for art practice is how these passions reflected on the ambiguous connection between reproduction and original. It’s a transgressive involvement that remains prevalent in the production of radical art to this day.

The Apparently Marginal Activities of Marcel Duchamp by Elena Filipovic is now available from The MIT Press.

martes, 21 de febrero de 2017

As Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ Turns 100: 14 Iconic Artworks It Inspired

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain hardly needs an introduction. Celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, the work was originally submitted for display at the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York City. Famously rejected by the committee, Duchamp instead exhibited the work at Alfred Stieglitz‘s studio to much fanfare.

Though the original has since been lost, 17 replicas were produced in the 1960s. Fountain is widely regarded as a seminal work in 20th century art for giving birth to the “readymade,” and has influenced countless artists since.

Here, we take a look at some of the most prominent artworks that have taken their inspiration from the concept of the readymade over the course of the last century.

Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram (1955-59). Photo ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, New York, courtesy Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

1. Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram (1955-59)Widely regarded as Rauschenberg’s most recognizable work, Monogram serves as a prime example of a “combine”—a term coined by the artist referring to the merging of painting and sculpture to create what he considered a wholly new medium of artistic practice.

As the goat was the largest object Rauschenberg ever used in a combine, the taxidermied animal became the source of much frustration: the artist made several versions of Monogram until, according to critic Calvin Tomkins, he was finally satisfied that “the animal looked as though it belonged in a painting.”

Piero Manzoni, Artist’s Shit (1961). Courtesy Wikiart.

2. Piero Manzoni, Artist’s Shit (1961)

Despite its seemingly straightforward title, Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit is actually shrouded in mystery, as nearly every aspect of the work—from its intentions and inspirations to its literal contents—remains hotly disputed.

Despite its seemingly straightforward title, Piero Manzoni’s Artist’s Shit is actually shrouded in mystery, as nearly every aspect of the work—from its intentions and inspirations to its literal contents—remains hotly disputed.

Supposedly conceived as a middle-finger of sorts to the art world at large, the work was produced in an edition of 90 tin cans total, each filled with 30 grams of what one can only assume is neatly-packaged shit.

In a 2007 text produced for the Tate, John Miller cites Duchamp’s influence, writing that despite Manzoni’s famous association with Yves Klein, “the most significant precedents” for the Italian artist’s infamous work lies within Duchamp.

Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (Soap Pads) (1964). Courtesy Wikiart.

3. Andy Warhol, Brillo Box (Soap Pads) (1964)

Warhol’s Brillo Boxes—plywood sculptures fashioned to imitate the unremarkable, everyday item—are arguably the quintessential variation of the readymade.

Warhol’s Brillo Boxes—plywood sculptures fashioned to imitate the unremarkable, everyday item—are arguably the quintessential variation of the readymade.

By elevating the mundane to the status of art object, Warhol explored how we might identify and value art—and made an updated take on Duchamp’s readymade by adding the question of commercialism to the equation.

Tom Marioni, FREE BEER (The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends is the Highest Form of Art) (1970-1979). Courtesy Hammer Museum/UCLA.

4. Tom Marioni, FREE BEER (The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art) (1970-1979)

For the original iteration of his ongoing installation and performance, California-based conceptual artist Tom Marioni invited 16 friends for a boozy after-hours get-together at the Oakland Museum of California. The beer, Pacifico, was supplied by the curator.

For the original iteration of his ongoing installation and performance, California-based conceptual artist Tom Marioni invited 16 friends for a boozy after-hours get-together at the Oakland Museum of California. The beer, Pacifico, was supplied by the curator.

Long after the shenanigans had died down, the empty bottles, chairs, and tables remained exactly as they were left behind, staying in place for the duration of the show, the party giving way to a readymade exhibition.

5. Jeff Koons, New Hoover Convertibles series (1981-7)

Comprised of vacuum cleaners displayed in Plexiglas cases, Koons’ series—dubbed “The New”—uses the readymade to explore how desire might be projected onto everyday objects.

Comprised of vacuum cleaners displayed in Plexiglas cases, Koons’ series—dubbed “The New”—uses the readymade to explore how desire might be projected onto everyday objects.

The appeal of Koons’ vacuums lie in their newness and the bright, shiny lighting under which they are placed. When speaking about the work, the artist said, “If one of my works was to be turned on, it would be destroyed.”

6. Isa Genzken, Weltempfänger (World Receiver) (1982)

Made of concrete, steel, and metal radio antennas, Genzken transforms standard concrete blocks into multi band radio receivers through a slight manipulation of the sparse materials: by simply adding chrome antennae.

Made of concrete, steel, and metal radio antennas, Genzken transforms standard concrete blocks into multi band radio receivers through a slight manipulation of the sparse materials: by simply adding chrome antennae.

Described by Art in America as Genzken’s “only readymade,” these sculptures, according to AiA writer Anne Doran, “introduce another of Genzken’s most enduring themes: the means by which the individual connects with the world.”

7. Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991)

Widely considered one of the most recognized symbols of British and contemporary art, Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living—consisting of a tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde in a vitrine—was once described by the New York Times critic Roberta Smith “synonymous with the YBA art scene.”

Widely considered one of the most recognized symbols of British and contemporary art, Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living—consisting of a tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde in a vitrine—was once described by the New York Times critic Roberta Smith “synonymous with the YBA art scene.”

The shark—for which Hirst shelled out a mere £6,000, upon instructing an Australian fisherman to catch something “big enough to eat you”—eventually decayed, after Hirst claimed the Saatchi gallery added bleach to the formaldehyde.

A replacement shark was again caught off the coast of Australia and shipped to London in 1993, to be placed in the original vitrine.

When asked whether the work remained the same, Hirst responded: “It’s a big dilemma. Artists and conservators have different opinions about what’s important: the original artwork or the original intention. I come from a conceptual art background, so I think it should be the intention. It’s the same piece. But the jury will be out for a long time to come.”

8. Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991)

The 1991 work by the late Gonzalez-Torres is a poetic representation of his partner, Ross Laycock, who passed away from an AIDS-related illness.

The 1991 work by the late Gonzalez-Torres is a poetic representation of his partner, Ross Laycock, who passed away from an AIDS-related illness.

Clocking in at about 175 pounds worth of individually-wrapped candies, the pile’s weight references Laycock’s ideal body weight.

Conceived as an interactive piece, the audience is encouraged to take a piece of the candy. As the heap begins to diminish in size, the work mirrors Laycock’s weight as his health declined. However, in act of love, Gonzalez-Torres specified that the pile be replenished on a regular basis to signify perpetual life.

9. David Hammons, In the Hood (1993)

Hammons’ 1993 piece featuring a hood severed from a sweatshirt is still, 24 years later, frightfully relevant today. The work conjures an image of lynching, or that of Trayvon Martin.

Hammons’ 1993 piece featuring a hood severed from a sweatshirt is still, 24 years later, frightfully relevant today. The work conjures an image of lynching, or that of Trayvon Martin.

As artnet News’ own Blake Gopnik wrote, “It’s just a scrap of industrial cloth, but hanging it on high evokes lynchings and maybe even Christ. (Another calculated move: Hammons has inserted a wire in the hood to open a space for an absent head.)”

10. Sherrie Levine, Fountain (Buddha) (1996)

As a pioneer of feminist art and member of the so-called “Pictures Generation,” Sherrie Levine remade works specifically by male artists in an attempt to undermine their role in the art world.

As a pioneer of feminist art and member of the so-called “Pictures Generation,” Sherrie Levine remade works specifically by male artists in an attempt to undermine their role in the art world.

With Fountain (Buddha), Levine made making an obvious reference to Duchamp but, by reworking the material of the urinal to cast bronze, she elevated its status from the mundane to art object.

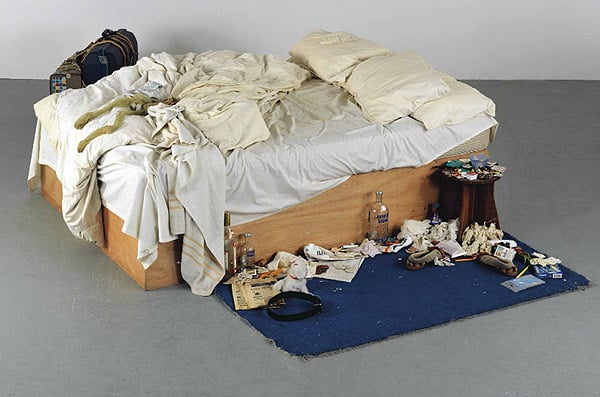

Tracey Emin, My Bed (1998). Courtesy of Tate.

11. Tracey Emin, My Bed (1998)

For her controversial Turner Prize-nominated work, Tracey Emin placed her bed and bedroom objects on display after she went through a depressive episode that had left her bedridden for several days, subsisting on nothing but cigarettes and alcohol (the remains of which can also be found on view).

For her controversial Turner Prize-nominated work, Tracey Emin placed her bed and bedroom objects on display after she went through a depressive episode that had left her bedridden for several days, subsisting on nothing but cigarettes and alcohol (the remains of which can also be found on view).

The work features several everyday objects, including those revealing the more graphic side of life: used condoms and menstrual blood stains. Critics chastized the work, claiming that it took no talent as anybody could exhibit a bed.

To these criticisms, Emin responded, “Well, they didn’t, did they? No one had ever done that before.”

Tom Sachs, James Brown’s Hair Products (2009, detail). Courtesy Tom Sachs’ Facebook page.

12. Tom Sachs, James Brown’s Hair Products (2009)

In his “James Brown” series, Sachs celebrates the man known as “The Godfather of Soul.” Because of Brown’s cult-like status, everyday objects from his lifetime have too been elevated to collectibles.

In his “James Brown” series, Sachs celebrates the man known as “The Godfather of Soul.” Because of Brown’s cult-like status, everyday objects from his lifetime have too been elevated to collectibles.

Sachs explores this phenomenon by preserving Brown’s items in clean, organized displays. The artist is admittedly “obsessed” with Brown and draws inspiration from him often.

Of the series, Sachs said to Surface: “I bought some of the objects, and I put them in reliquaries. I tried to elevate them, and treat them the way things like the Shroud of Turin are treated. I put his hair curlers in a cabinet in a mandala-like pattern … I wanted to present them as if they had belonged to the greatest man who had lived.”

13. Cyprien Gaillard, Today Diggers, Tomorrow Dickens (2013)

For his first exhibition at New York’s Gladstone Gallery, Gaillard explored the concept of the altered readymade by recasting construction machine parts as massive, imposing sculptures.

For his first exhibition at New York’s Gladstone Gallery, Gaillard explored the concept of the altered readymade by recasting construction machine parts as massive, imposing sculptures.

Rendered defunct by the process required to preserve these parts, the teeth previously used for digging on sites now act as sculptural anchors, and the heads are set with onyx, sitting where buckets once did.

“Once part of a machine used as a means for destruction, to encourage rejuvenation through building, these pieces, now preserved, begin a fossilization process of their own,” the gallery says of the works. “Though the diggers have caused destruction in their lifetime, in their arrested manner Gaillard has preserved them, imbuing them with new purpose.”

14. Maurizio Cattelan, America (2016)

Following his immensely successful 2011-12 retrospective at the Guggenheim, last September Maurizio Cattelan returned to the New York museum with America, an 18-karat gold toilet installed in a fully-functioning restroom that spawned a social media frenzy.

Following his immensely successful 2011-12 retrospective at the Guggenheim, last September Maurizio Cattelan returned to the New York museum with America, an 18-karat gold toilet installed in a fully-functioning restroom that spawned a social media frenzy.

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)

BLANCA ORAA MOYUA

Archivo del blog

-

►

2022

(14)

- diciembre (2)

- noviembre (2)

- octubre (2)

- septiembre (1)

- agosto (1)

- julio (2)

- junio (1)

- marzo (1)

- febrero (2)

-

►

2021

(27)

- noviembre (3)

- octubre (3)

- septiembre (2)

- julio (3)

- junio (1)

- mayo (4)

- abril (1)

- marzo (4)

- febrero (4)

- enero (2)

-

►

2020

(59)

- diciembre (2)

- noviembre (7)

- octubre (2)

- septiembre (9)

- agosto (5)

- julio (9)

- junio (9)

- mayo (5)

- abril (2)

- marzo (2)

- febrero (4)

- enero (3)

-

►

2018

(75)

- diciembre (2)

- noviembre (7)

- octubre (12)

- septiembre (13)

- agosto (1)

- julio (2)

- junio (6)

- mayo (2)

- abril (9)

- marzo (5)

- febrero (5)

- enero (11)

-

▼

2017

(131)

- diciembre (7)

- noviembre (2)

- octubre (16)

- septiembre (6)

- agosto (8)

- julio (11)

- junio (11)

- mayo (14)

- abril (16)

- marzo (13)

- febrero (13)

- enero (14)

-

►

2016

(399)

- diciembre (17)

- noviembre (28)

- octubre (16)

- septiembre (38)

- agosto (41)

- julio (46)

- junio (50)

- mayo (26)

- abril (11)

- marzo (45)

- febrero (43)

- enero (38)

-

►

2015

(317)

- diciembre (35)

- noviembre (9)

- octubre (26)

- septiembre (21)

- agosto (27)

- julio (30)

- junio (30)

- mayo (33)

- abril (24)

- marzo (33)

- febrero (26)

- enero (23)

-

►

2014

(279)

- diciembre (17)

- noviembre (29)

- octubre (29)

- septiembre (28)

- agosto (14)

- julio (26)

- junio (31)

- mayo (29)

- abril (22)

- marzo (18)

- febrero (5)

- enero (31)

-

►

2012

(2965)

- diciembre (189)

- noviembre (288)

- octubre (299)

- septiembre (311)

- agosto (136)

- julio (192)

- junio (263)

- mayo (289)

- abril (254)

- marzo (259)

- febrero (234)

- enero (251)