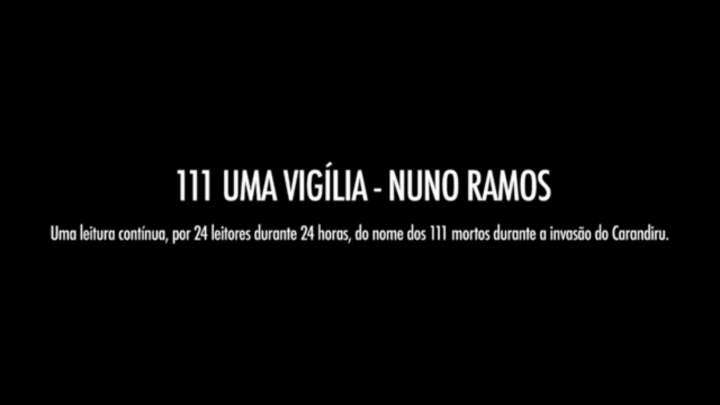

From November 1st to the 2nd, the artist Nuno Ramos held a 24-hour vigil in São Paulo for the 111 people killed in the Carandiru massacrein 1992. The November dates marked the passage from the Day of All Saints to the Day of the Dead, and coincided with the numbers 11-1. The massacre, one of the major violations of human rights in Brazil, was carried out by the police in reaction to a prisoner revolt in the Carandiru Penitentiary in São Paulo. After many years of impunity, in 2013 and 2014, 74 policemen involved in the massacre were convicted to hundreds of years in prison. However, the trial that sentenced the policemen was repealed in September, aggravating the sense of injustice and senseless violence perpetrated by the police in São Paulo today.

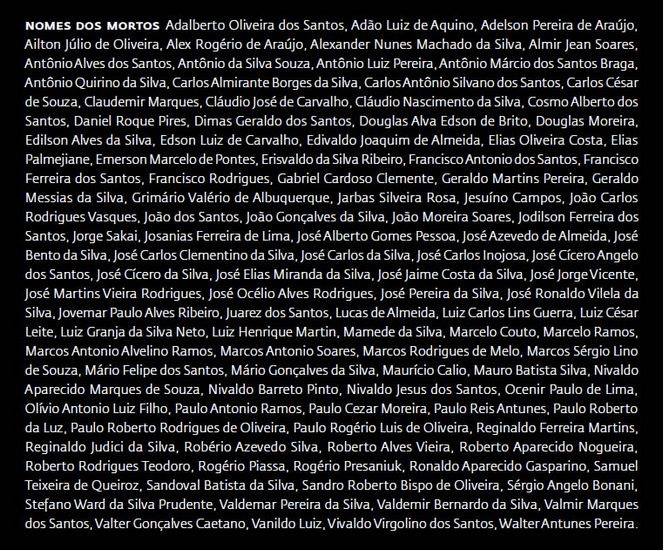

Ramos’s work, titled “111 Vigília, Canto, Leitura” (111 Vigil, Singing, Reading), remembers and gives life to the names of those who passed away. This is the second work that Ramos dedicates to the massacre. The first, completed in 1992, was an installation titled “111” that had 111 cobblestones covered with asphalt and tar. Twenty-four years later, Ramos gathered 24 people, among them artists, professors, filmmakers, writers, musicians, journalists, lawyers, and one survivor of the massacre (Sidney Sales), to alternate in reading the names of those killed by the police.

Each reader sat on the balcony or in front of the window of an apartment that looked out to downtown São Paulo. According to Ramos, the setting had the city as “a silent testimony” to the event. He told me his vision for the vigil was to have it function as a sort of antenna, on the top of a building, “irradiating and transmitting” the notion of citizenship and civility. The vigil was also live streamed through Facebook and YouTube and aired on the TV channel Cultura for 30 seconds live at each hour, which guaranteed that the vigil would reach the whole country.

Ramos resurfaces the memory of the Carandiru massacre during a moment in Brazil that is marked by state-sponsored violence. The crackdowns began in 2013, when people took to the streets against the increase in public transportation fares, and continued with the demonstrations leading up to the 2014 World Cup. But police aggression has intensified since Dilma Rousseff was impeached by the senate, which alleges she manipulated the state budget. In September, police violently dispersed protesters against the impeachment in São Paulo, using tear gas bombs, water jets, and rubber bullets. More recently, students protesting against state cuts on education were removed by force from the occupied schools. Among the readers invited by Ramos in the “111 Vigil” was Benjamin Lima, one of many students who has had encounters with the police during these recent protests.

There were a diverse range of speakers, which can be understood to symbolize the many social issues that have become pressing in Brazil following the change of political direction in the country after Rousseff’s impeachment, like the closing of borders to refugees and the lack of women and nonwhites in government. Though it’s important to Ramos that his work not to be considered ideological; instead, he sees the diverse group of readers as representative of his notion of civility. Other participants invited by Ramos included Congolese refugee Luambo Pitchou, businesswoman and activist Eliane Dias, feminist lawyer Isabela Del Monte, and transsexual woman and high-school teacher Paula Beatriz Souza Cruz. When I reached out to Cruz, she said that reading the names of those killed in the massacre had her thinking of how little has changed since 1992 and how much impunity reigns in Brazil. She added, “Every day this state massacres Brazilians, not giving them dignity and not respecting them.”

The vigil became a public event on Facebook, and, as anything that happens on the internet, there were many comments against and in favor of the project. Some deemed the vigil insignificant, and some more aggressive ones commemorated the massacre with the common saying, “the good bandit is the dead bandit.” The more sympathetic observations celebrated the power of art and the creative ways in which readers chose to present the list of names.

Ramos didn’t give any instructions to the readers, and stressed that there was no right or wrong way to present the names. Most of the readers started by saying the names slowly and carefully, but, as the vigil progressed, they took more liberties. Theater director José Celso Martinez delivered a euphoric and joyful reading, while actresses Barbara Paz and Helena Ignez raised and lowered their voices throughout their recitation, performing a range of feelings like anger, sadness, and tiredness. Cartoonist Laerte Coutinho similarly modified his voice throughout the reading, but assuming higher or lower, more feminine or more masculine tones of voice. Musician Paulo Miklos murmured a song at the introduction of his reading, and rapper Yzalú paused between words to stress the sounds of each name. Machado Calil, a professor of film at the University of São Paulo, read the list of first names and last names separately, highlighting a pattern of popular proper names, like José, repeated 16 times, as well as family names, like Da Silva. Film critic Jean-Claude Bernardet and writer Ferréz snuck phrases between the names: Bernardet intermittently stated, “All of them assassinated,” while Ferréz created imaginary descriptions for the people behind the names, like “Geraldo Messias da Silva, who was very quiet.”

This strategy of repeating names is a familiar and meaningful one in São Paulo, where tagging names on the walls of buildings has been for more than 20 years the basic tactic used by graffiti artists, known as the pixadores, to alert the population of São Paulo to those living in poverty, in the slums and along the peripheries of the city.

Yet the video streaming carried Ramos’s work beyond São Paulo — it was accessed by more than 400,000 people just on Facebook. The vigil situated the names of the deceased — that before would only be significant in police reports, legal paperwork, and newspapers — into a poetic format that can be accessed worldwide. Ramos’s work shows the importance of shared memory in honoring those who fall under social injustices and violence, and is a poignant artistic intervention in the highly politicized context of the internet. More importantly, “111 Vigília, Canto, Leitura” created a moment of sensibility and respect towards human life — something which seems to have been forgotten amidst the senseless violence and killings.

Nuno Ramos’s “111 Vigília, Canto, Leitura” (111 Vigil, Singing, Reading) (2016) took place in São Paulo on November 1–2.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario