As a functional object, the suitcase has a rather limited purpose—to get one’s stuff from point A to point B. But as a trope, luggage conveys serious metaphorical complexity and issues that need unpacking. Beyond being a symbol for emotional baggage, the suitcase is an emblem of mobility, evocative of all kinds of journeys, from the glamorous escapes of a jet setter or the bourgeois comforts of the family vacation to the forcible movement of exiles and refugees.

A suitcase can evoke a whole range of itinerant types, whether professional (the traveling salesman, the stage performer, the carnie) or more free-spirited (a drifter, purposely off the grid, maybe riding the rails). Over the years, numerous artists, not to mention filmmakers, playwrights, novelists, and songwriters, have employed the suitcase to great symbolic (and practical) effect. Below, we take a look at some of our favorites, from Dieter Roth’s cheese-filled bags to Zoe Leonard’s grids of stacked luggage.

Marcel Duchamp, Boîte-en-Valise

When Marcel Duchamp said, “Everything important that I have done can be put into a little suitcase,” in 1952, he wasn’t being self-deprecating. Rather, he was referring to his Boîte-en-Valise, or box-in-a-suitcase, the receptacle containing miniature versions of 70 or so of his artworks that he deemed “important” enough to reproduce and store together for collectors. Between 1935 and 1940, Duchamp created 20 editions of the Boîte, which are now dispersed across museums and private collections. Like a portable museum, the box unfolds to serve as a mini display wall for the diminutive works, which vary slightly between boxes—including combinations of Nude Descending A Staircase (1912), L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) (1915-23), and reproductions of readymades, including dollhouse-size urinals.

The boxes are kept in small, brown leather suitcases. (He later made more versions of Boîtes without valises.) The concept is classic Duchamp, who spent a lifetime flouting the art world’s fixation on originality and authenticity with his readymades, reproductions, and numerous variations of each. But the valise also has deep personal significance, reflecting Duchamp’s itinerant existence for many years. He moved from Paris, to New York, to Buenos Aires, back to Paris, and finally escaped to New York, in 1942, as the Nazis advanced to occupy the French capital.

Claes Oldenburg, London Knees, 1966

Claes Oldenburg, London Knees. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, March 26, 2016–March 12, 2017. © 2016 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Martin Seck.

For Oldenburg, the suitcase served as a container for a multipart work, but it also provided a means to convey a connection between art and consumer products. In the mid-1960s, as he was securing his reputation as one of the more irreverent Pop artists, Oldenburg created a series of fantasy proposals for mundane, blown-up objects—lipsticks, an electric fan, scissors—to be erected as civic monuments in cities across the world. London Knees (1966), a pair of women’s legs seen from mid-thigh to mid-shin, was meant to stand like giant twin towers in famous spots throughout London.

The idea came to him while installing a show in the city, where the “mini-skirt with go-go boots” trend caught his attention. He marveled at the paradox of “masculine voyeurism and feminine liberation” encapsulated in the fashions of the Swinging Sixties, and spoke of how the “architectural and fetishistic functions of knees were accentuated by the fashion of wearing boots with the mini.” The large-scale knee sculptures were never realized, but he did create a version of them—a maquette of polyurethane latex knees in an edition of 120, accompanied by 21 prints showing the towering legs in situ. He stored the set in a small suitcase, like a carrying case for wares peddled by a traveling salesman—a witty gesture reflective of his fixation on the intersection of commerce and art.

Dieter Roth, Staple Cheese, A Race, 1970

In 1970, for his first show in the U.S., the German-Swiss artist Dieter Roth stuffed 37 attractive suitcases with unwrapped blocks of cheese, from brie and camembert to cheddar. He installed them at the Eugenia Butler Gallery in Los Angeles, a short-lived yet highly influential hotbed of avant-garde experimentation at the time. Butler had helped Roth cull together the selection of unsullied suitcases, which, at the start of the show, were arranged in rows, as though waiting for their well-heeled owners. The scene conveyed something of the glamor and prosperity of the jumbo-jet era, but the whiff of bourgeois respectability was just a foil to the contents rotting within.

As part of the presentation, a suitcase was opened each day, increasing the appalling stench that wafted through the gallery. The cheese was a surprise to gallery-goers who weren’t familiar with Roth, but the notoriously experimental artist had a history with perishable materials, like chocolate and sausage. His inspiration here, however, came from an exhibition he first saw at the gallery—a selection of work by Fluxus provocateur George Brecht. Roth thought the work was “cheesy,” and insisted that Butler leave it on view through the duration of his own show, which also included “cheese races,” where chunks of cheese were thrown at the wall to see which oozed down to the floor fastest.

The suitcases soon became festering pools of maggots, and the health authorities attempted to shut down the show after three weeks, accusing Butler of using the gallery “to permit the breeding or harboring of flies.” After it finally closed, Roth built special storage containers to house the suitcases, and Butler apparently held onto them for some time—until her husband eventually dumped them in the middle of the desert.

Robert Gober, Untitled, 1997

Installation view of Robert Gober's Untitled (1997) in the exhibition “Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor” at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, on view October 4, 2014–January 18, 2015. Photo by Thomas Griesel. © The Museum of Modern Art.

The suitcase is an obvious symbol of secrecy, but Robert Gober took this idea a step further, transforming a piece of luggage into a portal to a private world. The large black case lies open on the floor, resembling someone’s unpacked luggage. But a glance inside reveals a metal grate covering a drain, which leads down to flowing water and a small tide pool. Tucked among clumps of seaweed and small stones are the bare legs of a man (a persistent Gober theme), alongside the legs of a child.

The work feels vaguely sinister, resembling a sewer of sorts, but it is also utopian—an escape from the drudgery of daily life. Gober’s Catholic upbringing informs much of his work, and it’s been suggested that the man and child might be an allusion to St. Christopher, the patron saint of travel, who carried the Christ child across a river to safety. More than anything, peering into the drain feels like stumbling upon something that’s not meant to be seen, even though what exists there might be lovely and magical.

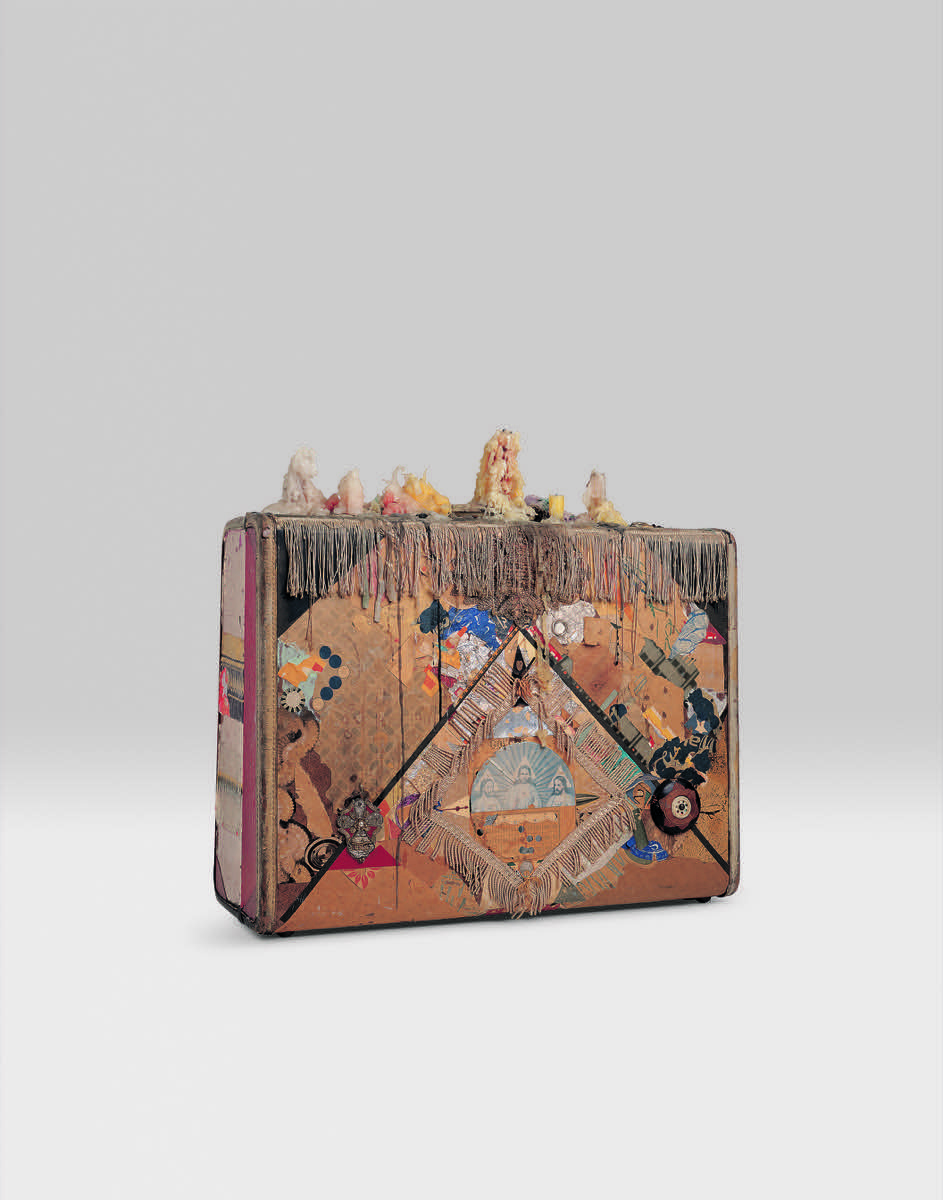

Bruce Conner, Suitcase, 1961–63

Suitcase with metal closures, paper, fabric, beads, fringe, candles, trading stamps, mirror, half of a yo-yo, fur, gold and silver foil, paint, and graphite 22 × 24 × 9 in. (55.9 × 61 × 22.9 cm) Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles

Resisting convention for much of his career, Conner defied the notion that an artwork is a static object whose final resting place is a museum or gallery. In the 1960s, in a telling gesture, he attached cloth handles to several of his found-detritus assemblages to make them portable. But in true Conner fashion, when it came to his Suitcase (1961–63), he rejected the defining characteristics of the object—portability, containment—instead transforming the piece into something functionless and decorative.

Melted wax, left from candles that once sat atop the suitcase, cover its handle and seal its opening. Using it as a surface, Conner covered the suitcase with collaged bits of paper, including an old image of what appears to be Christ flanked by Elijah and Moses, carefully framed with fringe resembling a liturgical garment. Well-worn and lovingly adorned, the assemblage could be a devotional object belonging to a spiritual nomad.

Conner had a knack for unearthing some of the darker aspects of Americana—violence, war, religious dogma—and this piece certainly fits into that history. But it also stands apart many of his other 1960s assemblages. He often layered his found materials—bits of lace, old photographs, broken furniture, fringe, feathers, clothing, and whatever else he could find—behind scrims of lady’s nylons to form box-like receptacles, but in this case it’s all surface, and viewers have no access to the interior. It feels strangely intimate, although its contents are sealed, never to be revealed.

Mona Hatoum, Traffic, 2002

Born in Beirut to Palestinian parents (who were, like other Palestinians, refused Lebanese citizenship), Mona Hatoum has made some of the most complex and trenchant work on the theme of exile. In this context, the suitcase reads easily as an emblem of dislocation, not to mention human or drug trafficking—a theme alluded to in the title.

The curiously eerie work consists of two suitcases standing next to each other, connected by human hair, which “grows” out of one and into another. It’s a rather minimalist way to convey all kinds of complexities about the human condition. It appears as though the woman once carrying the bags has vanished. And while the suitcases convey mobility, Hatoum has rendered them immobile. They feel less like travel accessories than cumbersome stand-ins for the body of their vanished owner.

Marcel Dzama, Untitled (Suitcase With Three Heads), 2007

As a keeper of transportable accessories, the suitcase is the ideal medium for an artist fixated on fantasy and masquerade, like Marcel Dzama. He has used suitcases in several of his sculptural pieces, often to contain costumes and other storytelling devices. This one contains three plaster masks and four handheld puppets. With its vintage, old-timey look and hand-made stage props, Dzama’s suitcase is a catalyst for the imagination, summoning images of an itinerant performer in a traveling vaudeville company.

Zoe Leonard, 1961, 2002

Photographer and sculptor Zoe Leonard has created several installations using empty luggage. This one, in the Guggenheim’s collection, is a conceptual self-portrait made from blue vintage suitcases, each representing a year of her life. Leonard adds another to the piece annually. Each suitcase is like a chunk of the artist’s psyche, or an impossibly tidy container of each year’s memories.

But the bags also resonate as signifiers of exile and displacement, given Leonard’s background. When 1961 was first installed at Paula Cooper Gallery, she juxtaposed it with photographs of her family in the years following WWII. Trapped in Warsaw during the war, her mother’s family was active in the Polish Resistance Movement. Then, as Soviets took over, her family escaped to Italy, where they lived for a decade before emigrating to the U.S.

The limbo of refugees, an all-too-familiar theme these days, comes to mind. But for all its rich personal associations, the installation also has its place in the tradition of abstraction. Numerous critics have noted its similarity to a monochromatic, geometric stack, with used suitcases standing in for perfectly formed blocks, as if the whole minimalist paradigm has worn down.

John Wesley, Suitcase, 1964–65

John Wesley, Suitcase, 1964–65. Image courtesy of Waddington Custot.

The exterior of a suitcase is the ideal surface for John Wesley, the only artist on this list whose primary medium is paint on canvas. Wesley has a flat, graphic style, and an appreciation for motifs gleaned from comics and advertising. Consequently, he has been considered part of the 20th-century Pop movement, but critics have also described his strange imagery as surrealist. His frequent motif of a nude pink woman folded in half merges the absurd and erotic as well as any Surrealist might. The suitcase itself, meanwhile, is prime territory for Pop appropriation, as a mundane, manufactured object that facilitates the consumerism of travel.

Wesley first created this work in 1964, covering a leather suitcase with painted canvas panels. The work’s whereabouts were unknown until it showed up in an auction in 2011, two years after Wesley collaborated with Beyer Projects to recreate the suitcase as an edition in bronze. The original shows a frontal and rear view of the woman on the bag’s two sides, while the recreation has pink daisies in her place.

—Meredith Mendelsohn

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario