“Société des artistes indépendants, Catalogue de la vingtième exposition, Paris,” (1904), David K. E. Bruce Fund (all images courtesy the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC unless otherwise noted)

Washington, DC — “Words could not express what an agreeable spectacle this was for me to see all at one time such a prodigious quantity of every kind of work,” wrote Jean Rou in his Mémoires inédits et opuscules. Rou, a French Protestant and historian, was attending the semi-public inaugural exhibition of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris in 1667, which was open to the public some 19 years after the Academy was founded by Louis XIV in 1648. Rou’s amazement at the breadth of the expansive exhibition prefigures the widespread influence that the Academy’s display, known as the Salon, would hold in the progression of European art in the 18th and 19th centuries until its decline following avant-garde and independent exhibitions of fin de siècle Paris.

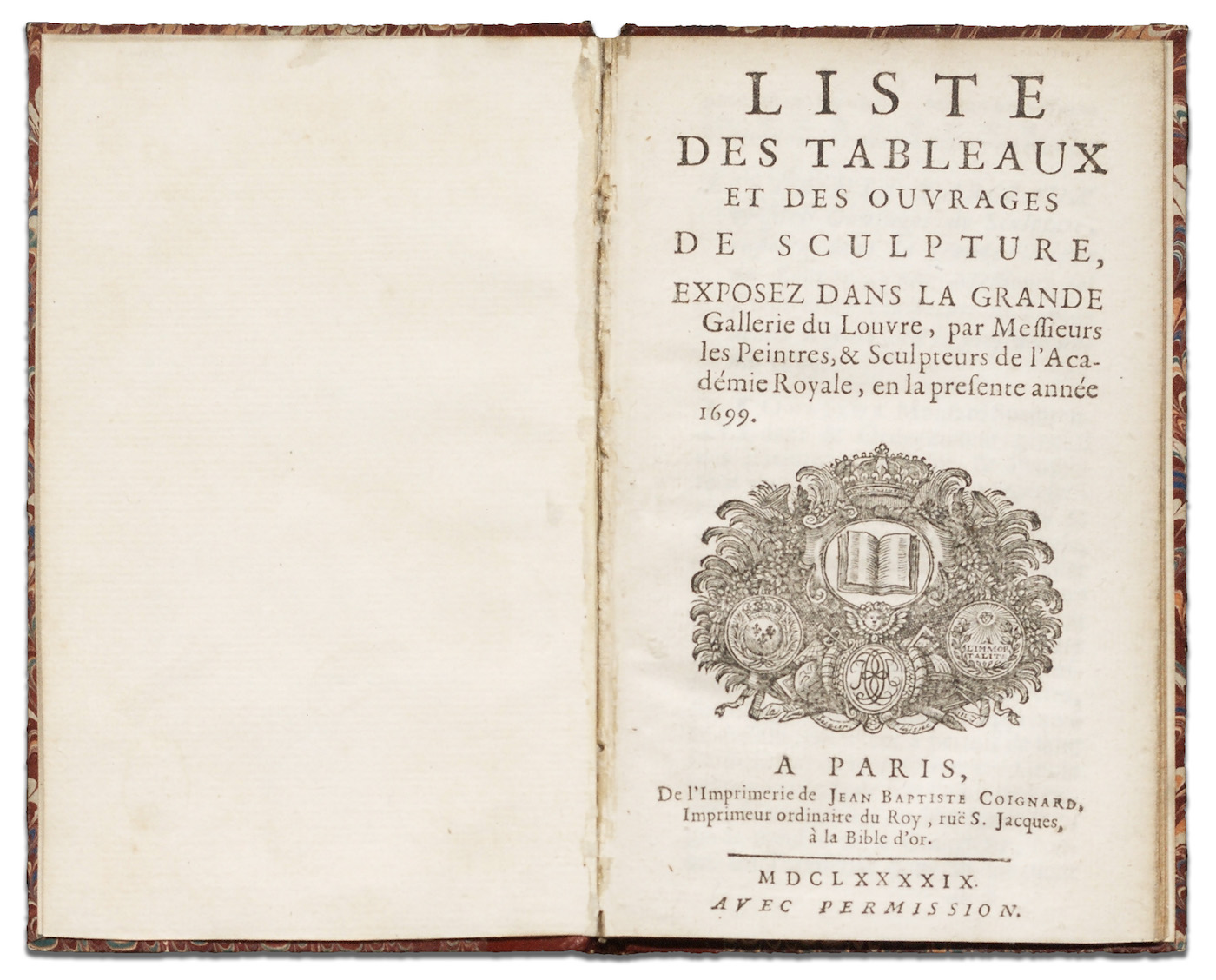

In the Library: Growth and Development of the Salon Livret at the National Gallery of Art’s East Building outlines the history of the Salon vis-à-vis the livret, or catalogue, first published for the Salon of 1673. Initially, the livret was little more than a pamphlet of listed works, organized by how they were displayed, and set in decorative paper. By 1742, thelivret presented the works in a less haphazard manner, numbered and organized by artist. In 1746, these catalogues included five essays by Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne, the first serious example of art criticism.

“Liste des tableaux et de ouvrages de sculptures, Paris” (1699), 6 x 3 3/4 in, 23 pages, unnumbered entries, David KE Bruce Fund

The key feature of the National Gallery’s exhibition of these catalogues is their chronology: by presenting a timeline of how they changed over time, it’s possible to glean a sense of how the Salon fell from being the singular authority of artistic accomplishment and how the history of art exhibition catalogues developed from being merely taxonomic and descriptive to interpretive and critical. Moreover, the evolution of the catalogues reflect developments in technology and society: typesetting and print techniques allowed for illustrations to accompany the descriptions of the art, first in black-and-white engravings and then later in color; the introduction of photography allowed even more veracity to these reproductions.

It is tempting to consider the Salon and the Royal Academy as impenetrable bastions of high culture that were immune to the trappings of contemporary life. However, the catalogues’ eventual incorporation of critical texts, which could influence how the exhibitions could be perceived, suggests that not only were the Salon exhibitions focused on modern life, they reflected it. The most obvious manifestation of this shift is seen in the growing size of these catalogues: the early livrets were only a few pages long but later ones included information on the judges, critics, biographies, etc., and ballooned to dozens of pages. The livrets suggested a new place for art history and criticism, one that could shape the taste of both its populace and signify the cultural authority of the republic.

“Wrappers and title page from Explication des peintures, sculptures, et gravures, de messieurs de l’Academie royale, Paris” (1767), David K.E. Bruce Fund

One needs only to examine the differences in catalogues preceding and immediately after the French Revolution to intuit that the traces of political turmoil were present in its pages. Prior to the Revolution, the French government commissioned works that would instill a sense of patriotism among viewers, most famously Jacques Louis David’s “Oath of the Horatii,” exhibited in the Salon of 1785. In the years of the Revolution, the exhibitions saw drastic changes: in 1791, the National Assembly opened the exhibition to all artists and changed the livret so that works would no longer be listed by academic rank. By 1793, the Royal Academy was abolished and the Salon exhibition for that year was managed by the Commune des Arts, who included in the livret an extended preface that expounded on the values of artistic freedom, tying it to the struggle for political freedom.

The greatest indication, however, that the Salon livrets were a product of their zeitgeist is in the decline of their popularity and distribution: at the turn of the century, beginning with the 1863 Salon des Refusés and continuing with the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne (all independent salons), the prevalence of exhibition catalogues outside of the traditional Salon indicated that the artistic milieu of France was in flux and that the old vanguard was no longer the sole determinant of artistic taste. Artists, dealers, and political forces increasingly pressured the selection committee to include more artists — the 1850 exhibition accepted some 4,000 entries — and this expansion is reflected in the size of the livrets. The increase in accessibility of the catalogues and the criticism that was contained within them, which promoted artists like Manet who rebelled against the traditional academic styles, reflected a more egalitarian approach to considering the elements that had so defined French culture during the 17th and 18th centuries.

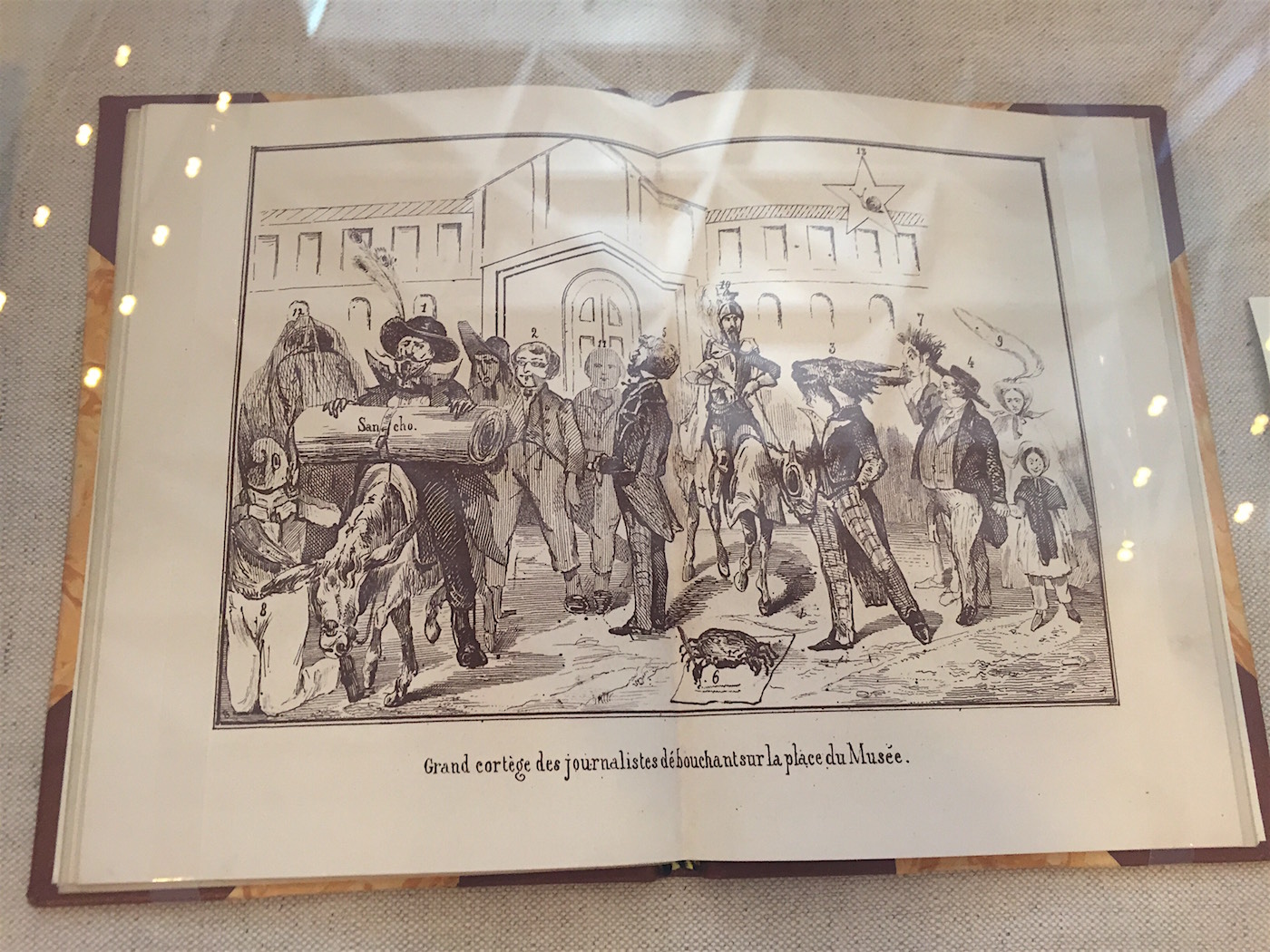

Japhet, “Le diable au salon: revue comique critique, excentrique et très-chique de l’exposition” (1814), David K. E. Bruce Fund (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Today, these early original catalogues are rare collectors’ items, but their lasting influence is the notion that even once an exhibition has been de-installed, its influence resonates. Artist books and contemporary digitization efforts for exhibition catalogues by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and other museums are strong indications that exhibitions are a product of society’s current tastes that extend beyond visual records and are a window into the socioeconomic realities of the time. The increasing democratization of this sharing of our impressions makes perhaps the best case for art writing to continue.

In the Library: Growth and Development of the Salon Livret continues at the National Gallery of Art’s East Building Study Center (6th & Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC) through September 16.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario