The writer lying on Carl Andre’s “144 Pieces of Zinc” (1967) at the Milwaukee Art Museum (all images courtesy the author)

MILWAUKEE — As I look at this photograph of myself, lying flat with arms outstretched on the Carl Andre, I wonder about my violation of museum etiquette. When I first sat down on the piece, in a meditative pose, a museum docent walked by. I feared a reprimand, but instead he said, “Oh, that’s my favorite thing to do too.” That’s when I decided to sprawl.

In this image, I notice how rather sickly three-dimensional I am, a little lumpy and so terribly complex with all my necessary human gear, like shoes and socks and patterned clothing and a scarf and glasses. I scrutinize what I’m wearing on this day and think it’s ridiculous. What does this outfit mean? Am I trying to look sophisticated but a bit funky, middle-aged but hip? It occurs to me that I got it all wrong. I hate that shirt and seldom wear it. I need new glasses. How did I gain those five pounds? I look at this picture and mostly see a flawed me. The fact that I’m lying on an artwork on a museum floor becomes a secondary concern. It strikes me that humans require so much, every day, just to make it outside the door. We are needy and demanding and fragile — rivers of heat and blood, sparking neurons, ticking pulses.

In contrast, Carl Andre’s “144 Pieces of Zinc” (1967) presents logic and order. My fleshy little pale fingers touch the straight lines of the grid. My feet dangle just beyond an edge. I am organized by this piece, redefined as a person who measures five 12-x-12-inch squares long, five 12-x-12 inch squares wide, with arms spread. I am the Vitruvian woman of 2016, collapsed on the floor of the Milwaukee Art Museum, feeling the cool panels of zinc, the hard ground, the almost protected space — feeling there is something just a little sacred in this crucifixion-like act. Perhaps the 600-year history since the Renaissance, when man became the measure of all things, is what supports my back. I look at the picture again and see it a bit differently, though: all things are measurements of a universal language. Andre taps into a simple kind of perfection here, then lets us crush our heels on it.

These gray, heavy zinc plates now have foot scuffs from years of museum visitors’ treading. Zinc is a chemical element whose symbol is Zn and atomic number is 30. It melts at 787.2°F. Zinc is a dietary mineral we need to survive. In industry, it’s frequently used as a coating on steel and iron for corrosion protection. Carl Andre made this piece out of zinc because he made all of his Minimalist work out of materials used in construction or industry — wood, steel, lead, copper, brick. These materials did not bring art-world associations with them. They were less rarefied and more familiar from their worldly uses, offering less separation between our lived experience and our artistic one, or perhaps helping us notice the hidden particulars of both.

When I lie on my back, I allow Carl Andre to define my space. I look at the bland ceiling. If I bend my head and look past my toes, Sol LeWitt’s “Incomplete Open Cube 9-12” (1974) sits stalwart and elegant, its open form seeming to breath in and filter the air of the space. If I tilt my head back, I see LeWitt’s delicate, penciled “Wall Drawing #88” (1971), with a dizzying number of small, lightly drawn squares, each of which contains a varying line pattern. LeWitt redefines our idea of a drawing by having assistants make it directly on the wall, based on his written instructions — like a game. LeWitt has us meditating on the notion of a wall. Andre puts us in touch with the space of the floor. I decide that this is, indeed, a good place to lie on one’s back.

* * *

Whether it’s the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City or the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM), institutions are now asking us to do what Carl Andre requested of us 40 years ago: interact with the work. But this time we must “generate content” via our cell phones. Selfies and snapshots are not only encouraged but celebrated, with apps and national #museumselfie days (January 18, 2017 is the next one). We are given a hashtag upon entering museum spaces as easily as we once were given a sticker or small lapel pin to validate our entrance fee. In a sense, the pressure to interact and perform within art museums is a way to provide concrete feedback to the institution that we enjoyed our visit. Who doesn’t want such feedback? When we post a photo of our experience on social media, it springs forth into the world as a giant LIKE and encourages others to undertake the same adventure. This is marketing at its best: free, broadly disseminated, playful, harmless, and focused on that sought-after demographic — youth. Last year it was estimated that selfies with and photographs of Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass” tagged #lacma (for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art) were potentially reaching 175,000 people a week.

In his article “The New New Whitney,” Jerry Saltz quotes fellow critic Holland Cotter as defining museums as “places where looking is a way of knowing the world and ourselves.” Saltz then notes that “museums have changed.” He says the museum once “was a place of insightful exploration of the present in the context of the long or compressed histories that preceded it.” It’s become “a reved-up showcase of new, the now, the next, an always activated market of events and experiences” — more like a visit to Graceland. “Shut up, take a selfie, keep moving.”

This new emphasis on viewer engagement (#shutupandtakeaselfie), whether good or bad, does change the relationship between person and institution. It’s almost the difference between a hook-up and a date. We once entered museums with no expectations. The museum’s job was to preserve and present artworks in ways that communicated information and historic context. They were the trusted authority, we were the receptors of uplifting encounters, often full of hope and faith in the endurance and ultimate goodness of humanity. Information was given and we absorbed it, while finding space for our own observations or thoughts. The relationship grew slowly. Today, by contrast, we walk in and we’re pressured to perform.

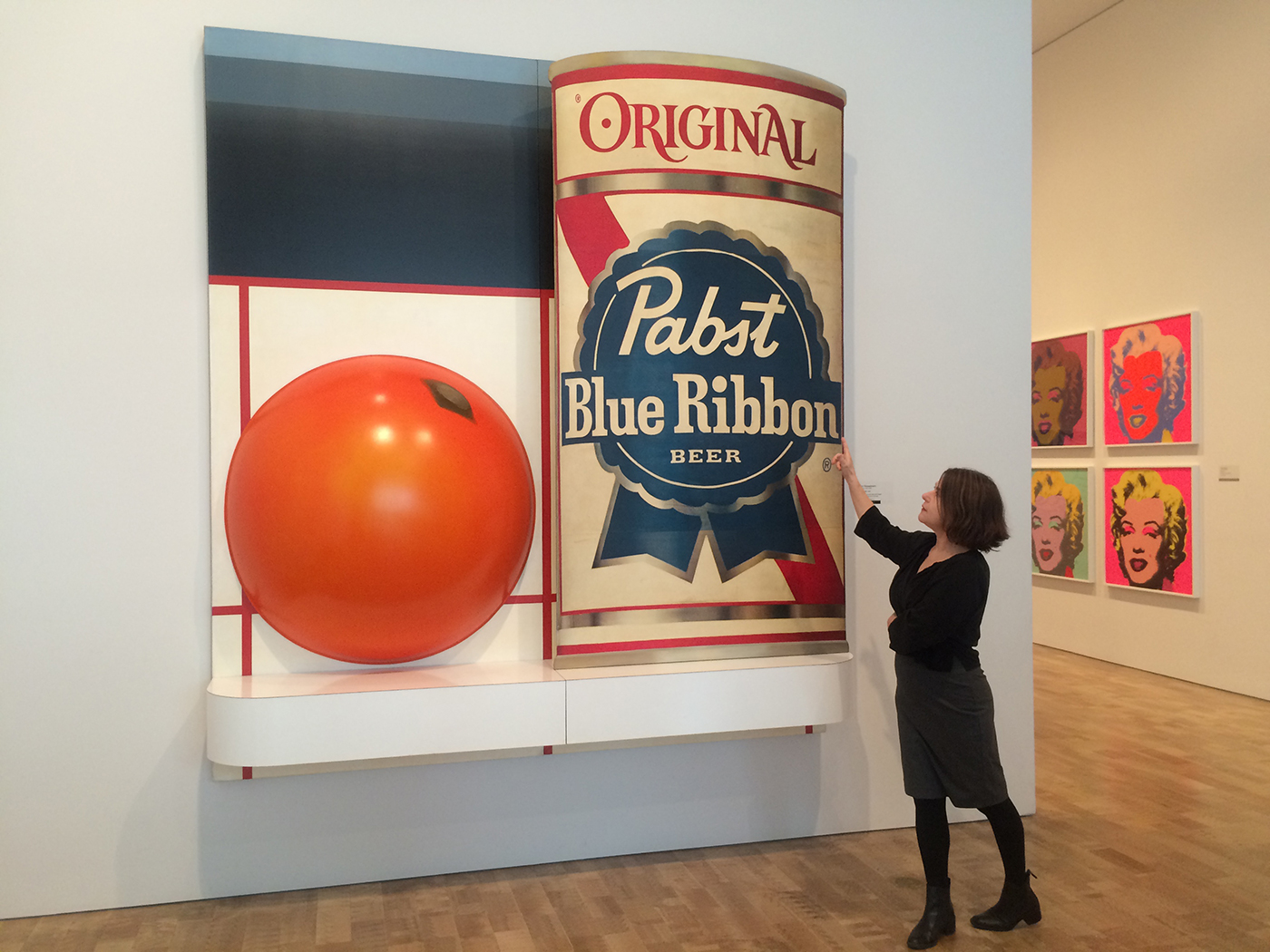

The author with Tom Wesselmann’s “Still Life #51” (1964), at the east gallery entrance to the permanent collection

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s recently opened, $34 million, 17,500-square-foot lakeside addition by local architect Jim Shields, as well as its renovated and reinstalled permanent collection, seem especially well suited for this shift in visitor participation and engagement. One could even argue that the addition was designed and the changes made to accommodate the gamesmanship that’s now encouraged. Long vistas, large-scale works, a full room of contemporary sculpture — so many things with razzle-dazzle. This may be a great advancement in museum practice, a way to open up the fetid atmosphere of too many glass vitrines and enshrined totems. Peering at thousands of years of history or even 100 years of modern art can be intimidating. Perhaps this is why we now enter MAM’s permanent collection via the east arm of the exuberant Santiago Calatrava addition built in 2001 — not, as we once did, through ancient history (mummies, Greece and Rome). Now, we are greeted by a giant Tom Wesselmann, a 1960s Pop art composition dominated by an eight-foot, three-dimensional can of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer. Not only are you in Milwaukee (brats, beer, and cheese), you’re about to have a good time.

As one of the first and probably most important artists of the 1960s to blur the lines between sculpture, painting, and functionality by positioning his artwork on the floor, Carl Andre put art in our path, and he put us in the art. Forty years prior to today’s ease with public performance, Andre asked us to defy the hands-off/step back/don’t touch limitations of the art world. His sculptures, like “144 Pieces of Zinc,” are meant to be walked on. In a way, this act demeans the work. You cannot walk across a Carl Andre grid without feeling that you’re stepping on it, both literally and figuratively. Many people refuse to tread on it out of a general reverence and respect for art.

I walk across it because I like how it generates a little current of guilt. No matter how many times my heels click on its gray metal surface, it feels disconcerting. Andre makes us question our museum behavior. He entreats us to look down and feel a sense of contact with the floor and materiality of the piece; he also gives us a small surround or enclosure in which to stand and take in the rest of the room. When we stand on an Andre piece, the art defines the self. We have boundaries and a new perspective, a manifestation of place. It becomes apparent that everything we view is in relationship to the physicality and sensory limits of the self. Andre was prescient enough to acknowledge and facilitate that. Perhaps taking our own pictures in front of a Rothko or within an new immersive light field by Anthony McCall, or grinning at the perpetually hangdog Francisco de Zurbaran’s “St. Francis of Assisi in His Tomb,” helps us experience a full physical engagement with the act of seeing.

Larry Bell’s “Untitled” (1972), made of glazed glass, offers the perfect selfie opportunity. (click to enlarge)

In a catalogue essay from Carl Andre’s 2014 retrospective at Dia:Beacon, the curator Yasmil Raymond writes, “The experience of art is a displacement, the crossing of a threshold, or path, whereby we are invited to examine the verticality of bodies in opposition to the ground.” In an article in The Paris Review Daily about the exhibition, writer Andy Battaglia quotes fiction writer Don DeLillo: “Maybe objects are consoling. … Do people make things to define the boundaries of the self? Objects are the limits we desperately need. They show us where we end. They dispel our sadness, temporarily.”

If this is true, that objects are comforting because they secure us within a relational boundary, then perhaps it’s more natural than one would think to experience art via images that put us alongside it. As narcissistic and self-obsessed as the process might seem, is it possible that pictures that document this equation of self and object might simply be an extension of the way we already unconsciously process art?

What if I hadn’t had a picture of myself taken lying prone on the Carl Andre piece on an unseasonably warm day in January? Without the photograph, I certainly wouldn’t have been able to access these thoughts. The undocumented experience would have vanished from my mind as quickly as a small scoop of gelato, an April icicle, a Snapchat post. And I certainly wouldn’t have been struck by a disconcerting memory that arose with an unexpected jolt.

Carl Andre was accused and later acquitted of pushing his third wife, the artist Ana Mendieta, to her death out of a 34th-story window in Greenwich Village in 1985, in the early morning, apparently during a drunken lovers’ fight. Whether it was murder, accident, or suicide, the event derailed Andre’s career. Fellow artist and friend Frank Stella posted the $1 million bail to have Andre released from confinement. The weight of all of this occurred to me as I looked at my picture and realized I was inadvertently reenacting this tragedy on the surface of a Carl Andre floor piece in the middle of the Milwaukee Art Museum.

The writer lying on Carl Andre’s “144 Pieces of Zinc” (1967)

To walk over these squares of zinc, while once a guilty pleasure, now carries the weight of a memorial ritual. Infused with the hush of human disaster, the cool Minimalism that was intended to provide a pure experience of texture and being, of surfaces and relations, without the imposition of authorship and emotion, feels like a deflowered utopia, a full-on mess of human entanglement and pain. All because of an iPhone photo.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario