Anna Uddenburg, “Transit Mode–Abenteuer” (2014–16), installation view (all images courtesy of Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art; all photos by Timo Ohler unless noted)

BERLIN — New York fashion collective

DIS utterly

dis-appoints,

dis-integrating the

Berlin Biennale, what was once one of Europe’s most socially engaged and politicized biennales, into a bricolage of ahistorical rubbish, second-rate post-internet aesthetics, and crass co-branding opportunities. The exhibition,

The Present in Drag, includes work from 50 “artists,” set across five sites, supported by an overwhelming number of brands and product placements that it is what philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin would have likely described as an exoskeleton of late Western capitalism.

Between 1927 and 1940, when Benjamin wrote the fragments that would later become The Arcades Project, he envisaged how, during the late 19th century, European ideas relating to technology and consumerism were beginning to lead to extreme social regression, which he connected to industrial capitalism, the First and Second World Wars, totalitarianism, and genocide. In his ambitious and unfinished project, which can be applied not just to the 19th century but also to the present day, including this year’s Berlin Biennale, Benjamin mapped out how the grounds of modernity, bound to the mythical ideas of progress and technology, foster a sense of alienation. In doing so, the emergence of “arcades,” as Benjamin defined them — literally the structures that created passageways through blocks of buildings lined with stores and shops, which first appeared in Paris during its transformation under Seine Department Prefect Georges-Eugène Haussmann — formed new liminal spaces that created false indexes of public freedom bound to social dreams of utopia.

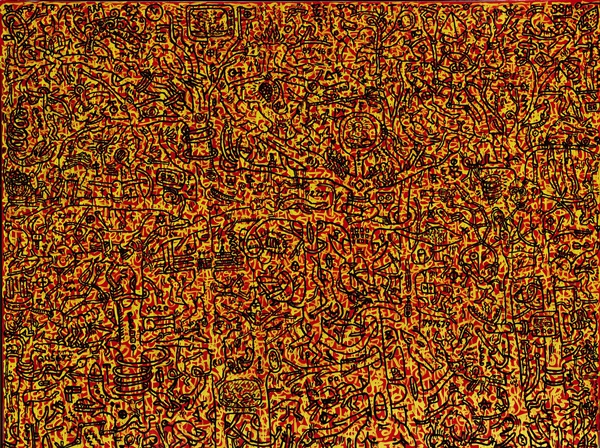

BB9 visual element, 3D design by Filip Setmanuk (2016) (photo by Natasha Goldenberg) (click to enlarge)

The arcades of 19th-century Paris, though billed as free and open public spaces, were in reality just marketplaces for the materialization of commodity fetishism, mass spectacle, and desire. Rather than the flâneur, the strolling figure of the new city and urban environment described by Charles Baudelaire, Benjamin dubbed this the emergence of a new “spectatorial mass.” And rather than producing actual unification of peoples, Benjamin’s spectatorial mass exacerbated the reality of class difference vis-à-vis commodity fetishism, shopping, leisure, flânerie, self-display, and hyper-individualization.

Nearly a century later, many of Benjamin’s ideas still apply. In truth, the spectatorial mass of the 19th century is now abetted by the glittering light and constant digital feedback of the Internet, where today’s arcades and boulevards, once illuminated by streetlights above, now pulsate down an information superhighway lined with social media, online shopping, the “sharing” economy, leisure, and, ultimately, digital alienation.

The ninth Berlin Biennale opened to the public on June 3, 2016, curated by highfalutin fashion collective DIS, a media entity that seems more concerned with upcycling art-world trend reports, cyber-utopianism, digital flânerie, and looking cool in Slavoj Zizek t-shirts than in curating anything that could remotely be considered a serious, relevant, or important exhibition of contemporary art.

The exhibition is set across five sites: the Akademie der Künste, the ESMT European School of Management, the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, The Feuerle Collection, and a Blue Star sightseeing boat. The artifacts, tactics, surfaces, and experiences found in these locations attest to an endless interplay of apathy and irony.

Indeed, since the announcement in 2014 that DIS — composed of Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso, and David Toro — were to be curators for BB9, speculation has run rampant that one of the continent’s most vital institutions of contemporary art would be transformed into a marketing gimmick of “post-Internet” vanity aesthetics, design, and fashion masquerading as art. The foursome are co-founders of DIS Magazine, an online digital media platform that bills itself as exploring “tension between popular culture and institutional critique, while facilitating projects for the most public and democratic of all forums — the Internet.” At a press conference last February, Boyle spoke about their intentions for infusing BB9 with potent dualisms. “Our proposition is simple,” she said. “Instead of pulling talks on anxiety, let’s make people anxious; rather than symposia on privacy, let’s jeopardize it; instead of talking about capitalism, let’s distort it […] instead of unmasking the present, this is the present in drag.”

DIS, curatorial team of the 9th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (photo by Sabine Reitmaier)

Initiated nearly 20 years ago by curator-cum-laureate Klaus Biesenbach, the Berlin Biennale has, under DIS’s curation, transformed from one of Europe’s most critical pinnacles of contemporary art into a vast obsolescent pageant of irrelevance, a disposable co-branding opportunity made to measure for privileged shareholders with little (if any) connection to the numerous issues facing Germany, Europe, or the international community today.

Instead, what DIS have come up with is an exhibition so vacuous, ideologically apathetic, ahistorical, sarcastic, and dehumanizing, it’s a wonder it hasn’t been blacklisted solely on account of its conformity to commodity fetishism. Not to mention their ignorance of current events shaping Europe — like the refugee crisis, the rise of the Alternative für Deutschland party, Brexit, neoliberalism, austerity, and the privatization of art, culture, and education. The exhibition is pieced together from the organizers’ unfettered acceptance of corporate culture, branding, product placement, and spectacle. Benjamin would likely have described it as an exhibition where a “circus-like and theatrical element of commerce is quite extraordinarily heightened.”

Directly outside the infamous Brandenburg Gate is one of the main exhibition venues, the Akademie der Künste (AdK), on the second floor of which Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch’s wearying video installation, “As yet untitled sculptural theater” (2016), invokes the immediacy of hyper-obsessive interactions. Their project is based around two new movies — Mark Trade and Permission Streak — commissioned specifically for the Biennale and made from the artists’ archival material dating back to the 1990s. In each, character-driven sketches are set to flash points of absurdity, with uncoupled dialogue between individuals interrupted by bursts of visual effects and animation. As characters engage in hopeless asymmetrical banter, it dawned on me that Trecartin and Fitch’s work hadn’t changed much over the last decade and a half.

Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin, “(As yet untitled sculptural theater)” (2016), installation view (all photos by Timo Ohler unless noted)

In a way, I feel bad for Trecartin and Fitch, whose work was at one time somewhat interesting and important, but has remained relatively unchanged since their

mid-career retrospective at the Musée d/Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2012. In the years since, the duo has been merely replicating their same tired format over and over, likely due to pressure from gallerists and/or the art market, which made me think how much more stimulating their aesthetic would be with more performative elements. Even though I felt totally exhausted from their project at BB9, it would have been so much more interesting if Trecartin and Fitch began orchestrating performances, rather than video installations.

Directly across from Trecartin and Fitch, “In Bed Together” (2016), a work by M/L Artspace (Lena Henke and Marie Karlberg), seems to completely appropriate Trecartin and Fitch’s aesthetic. The work felt to me like high school party sponsored by Bed Bath & Beyond and Material Vodka. (Note: The project was actually sponsored by Bed Bath & Beyond and Material Vodka). The video installation included scores of individuals wearing sheets and a bed screenprinted with quotes so sarcastic, dry, and apathetic, the inanity and shallowness of the interactions in the piece made me think I was becoming more lame-brained by the minute.

M/L Artspace, “In Bed Together” (2016), installation view

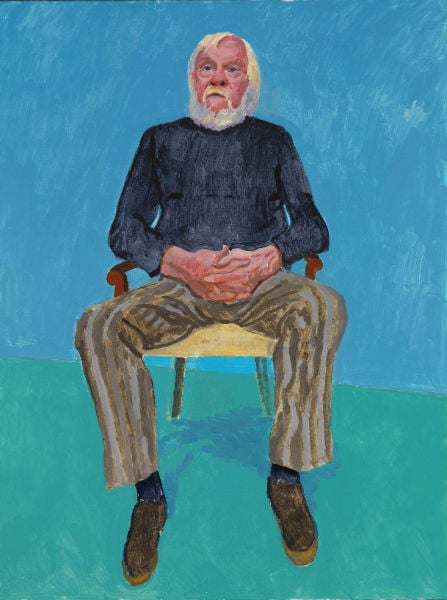

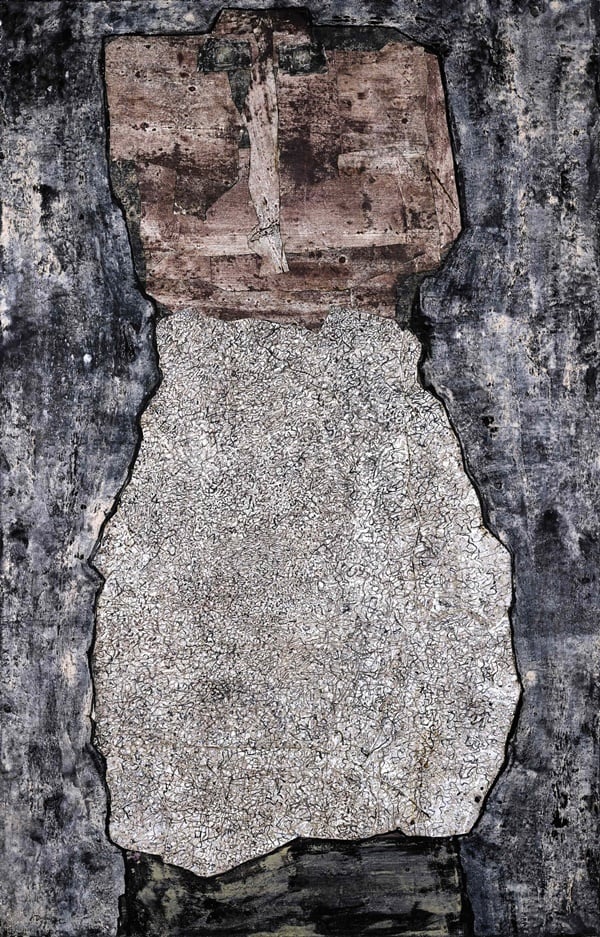

Anna Uddenburg, “Transit Mode–Abenteuer” (2014–16), installation view

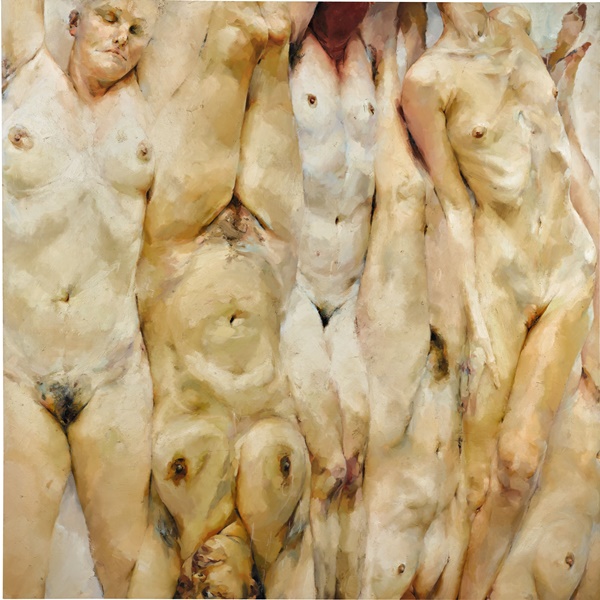

Also at AdK, Anna Uddenburg’s “Transit Mode–Abenteuer” (2014–16) takes the form of sculptures spread throughout the building depicting women emerging from suitcases in highly sexualized positions. According to its description, this work is meant to examine “body culture, spirituality, and self-staging,” but rather than holding up the issue of femininity to any sort of critical or concerning perspective, it simply conforms to ignorant gender stereotypes. Uddenburg’s work emphasizes tasteless voyeurism, attempting to use gender theory to mask what is otherwise a very crass depiction of women. Instead of drawing attention to important women’s issues, like

the enhanced risk of gender-based violence unique to female refugees in Germany, Uddenburg’s sculptures merely objectify the ways in which women are all too often portrayed, leaving nothing to the imagination other than some thinly veiled trope of superficial acquiescence to gender theory.

On the terrace of the AdK, Jon Rafman’s “View of Pariser Platz” (2016), offers a site-specific experience of Brandenburger Tor seen from above, using Occulus Rift technology. It’s a nearly four-minute-long virtual-reality experience that re-articulates Pariser Platz with violent and erotic encounters, meant to provoke a sense of simulacrum, a complete distanciation from reality itself. This piece is emblematic of everything that is wrong with BB9: While the world is crumbling down around us, we are asked to don the Occulus Rift and forget all about it. It would have been great to see Rafman’s work demonstrate the slightest bit of sensitivity to the immense social and political importance of Pariser Platz — the site itself, not as a place full of zombies and lifeless falling bodies, but one where alternative social horizons, movements, and events could be imagined.

Jon Rafman, “View of Pariser Platz” (2016), installation view

Hito Steyerl, “ExtraSpaceCraft” (2016), installation view

In the basement at AdK, Hito Steyerl’s “The Tower” (2015), a three-channel HD video installation developed in collaboration with David Riff, Nicolas Pelzer, and Maximilian Schmoetzer, is among the more praiseworthy and worthwhile works in the exhibition. It examines a master plan developed by Saddam Hussein to build a modern Tower of Babel, inundated with Steyerl’s aesthetic of layering images with digitized renderings, in addition to footage taken from a drone operated onsite. Juxtaposed with a fictional technology and programming firm commissioned by Ukraine to prototype conflict situations, the piece speaks at once to architectural references and contextual ideas relating to simulation, mythology, observation, surveillance, war, and geopolitics.

Another of the more palatable works in the exhibition is American artist Cécile Evans’s video installation, What the Heart Wants (2016), which offers a modicum of criticality set within an immersive environment that includes a room flooded with water and a catwalk leading up to a large screen projecting images of a fictional dystopic world, while a voiceover debates what it means to be human. From the experiences one derives from the digital age, consumerism, political disenfranchisement, and emotional desires, the work reminds me of Benjamin’s panoramic analyses meant to provide orientation within the antinomies of capitalism. In Evans’ work, Benjamin’s spectatorial mass is laid bare as “isolated words [that] have remained in place as marks of catastrophic encounters.” The uniqueness and originality of both Steyerl and Evan’s work is important because it gives some intellectual weight to what is otherwise an exhibition catering to philistines and annoying PR types.

Cécile B. Evans, “What the Heart Wants” (2016), video still

Christopher Kulendran Thomas, “New Eelam” (2016), installation view

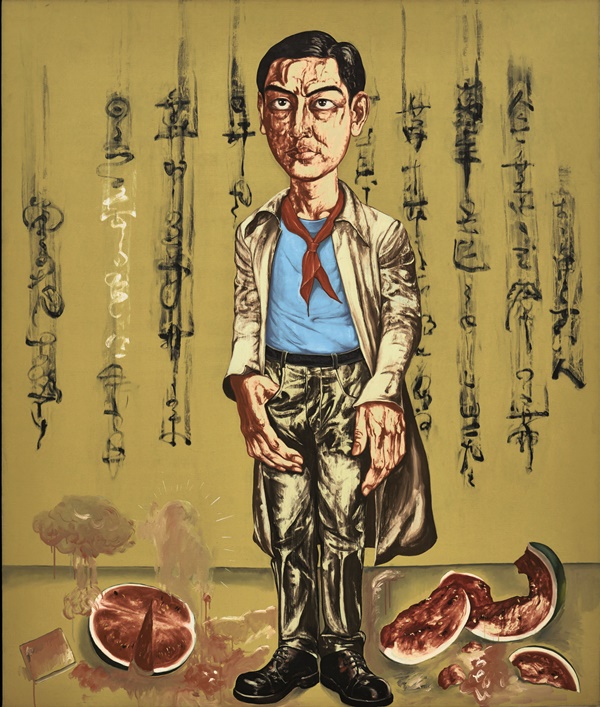

Verschiedene Materialien Mixed media

Other works in the exhibition include a woman lip-synching the lyrics to Fetty Wap’s “Trap Queen” and a project billed as a startup application envisaging the total AirBnB-ification of everyday life by Christopher Kulendran Thomas. Entitled “New Eelam” (2016)—a reference to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, an armed utopian group in Sri Lanka violently crushed in 2009 by a Western-backed government—the work is set within a real-estate show room, and includes a video that offensively aims to laud the benefits of “liquid citizenship […] to provide a flexible subscription model for apartments […] based on joint ownership.” The narrator in the video praises “soft ethnic cleansing” in favor of creating a flexible subscription model for shared housing.

Outside in the courtyard at KW, a giant Rihanna statute is installed seemingly for the sole purpose of providing selfie opportunities, which organizers have been promoting under the hashtag #biennaleglam.

Urgh.

The majority of the exhibition feels like a prosthetic pop-up shop, simulated with a sense of faux rebelliousness — like if Andy Warhol met Guy Debord on Grindr, started collaborating, then decided to redeploy commerce and culture in a self-critical and self-congratulatory kind of way.

Not surprising, given that DIS is essentially a retail assemblage of creative stock-image propagandists, the exhibition also offers a vast array of “collectible” products, like 90€ Telfar cotton tank tops, expensive “artist”-made mint juices, so-called “Hater Blocker Contact Lenses” by Yngve Holen that are billed as “protective charms,” projects in collaboration with über-brosocialist brands like HBA (Hood by Air), and performances about the Internet like “How to DISappear in America: The Musical” (2016), which was so painfully kitschy I started to think the whole thing was a joke. Consequently, the entire exhibition felt like it was made for a group of relevant stakeholders. Even just walking through it, I felt like I was unscrupulously participating in a giant money-laundering operation tailor-made for brands seeking to amass cultural capital.

Files, gadgets, video installations, co-branding opportunities, cultures, conflicts, natural disasters, memes, technologies — BB9 is filled with works that attempt to replicate a kind of “critical” consumerism but instead simply conforms to it. I was constantly dissatisfied by the objects on display, always sure there was something better just beyond my affordability or knowledge, stretching BB9 to new heights of art-world FOMO (Fear of Missing Out). Hence, the exhibition’s superficially draws attention to a multi-polar, mobile, post-democratic, post-conflict world, where the real-time conditions and information we are presented with becomes rearticulated to the tune of cherry-picked ideologies, brands, styles, and cultures.

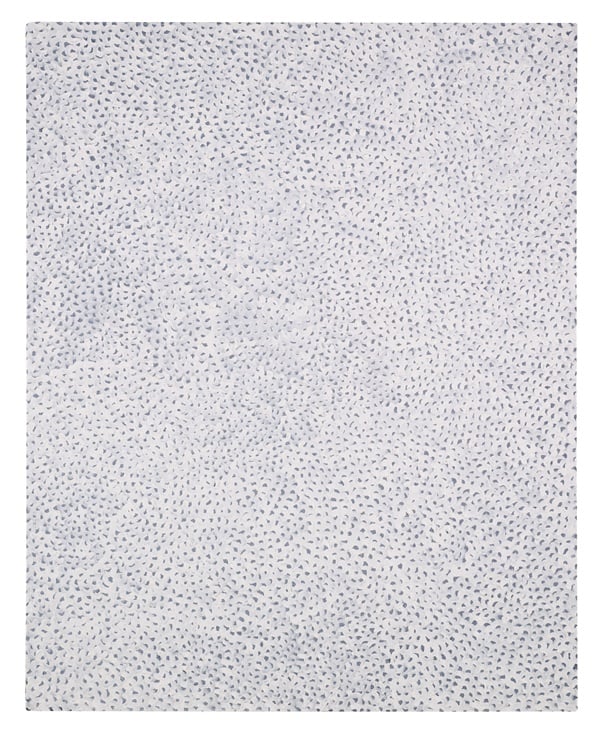

BB9 logo

Contrast this to 2012, when the seventh Berlin Biennale, under Artur Żmijewski’s curatorship, was conceived as a way of directly impacting district politics and the landscape of the city itself. BB7, for me, was a veritable how-to manual for a socially engaged curatorial methodology, witnessing art’s transformation into a social tool, broadening the discussion not of what art is, but of what it could be. At BB7, Martin Zet’s project took the form of a giant book-burning attempt calling for the collection of Thilo Sarrazin’s bestselling racist and xenophobic Deutschland schafft sich abat, using the platform of the biennale to trigger a broader political debate about immigration and identity within German society. The political engagement of BB7 also took the form of activists from M15 and Occupy, who were invited by Żmijewski to form international work groups on the ground floor of the KW, and numerous other public projects, seminars, debates, publications, policy issues, ideas, and workspaces were conceptualized, created, and disseminated as a result.

Comparatively, BB9 lacks any probity or concern for the present. It feels like a huge existential Apple ad transfiguring the space of art into something lacking any sincerity, art-historical reference, or concern for the social or political consequences of the events that are presently shaping Europe, much less the city of Berlin. BB9 places an emphasis on escaping the type of “artivist” practice emboldened by Żmijewski and others, but in doing so, it negates any positive social vision in favor of fantasy, spectacle, and commodity fetishism. Just as Benjamin connected the emergence of arcades to the newly formed spectatorial mass, false indexes of public freedom, and social dreams of utopia in the 19th century, so too does BB9 conform to a mythical idea of progress bound by technology, a gesture that feels overwhelmingly empty, vacant, and depleted.

In truth, it is difficult to insist that art

has to aspire to participate in and change social and political disparities. Yet it is entirely different to disdainfully poke fun at art that tries to serve a greater social purpose. “Why should fascists have all the fun?” an advertisement for BB9 offensively asks. A new book,

Towards a Conceptual Militancy (2016), by curator and theorist Mike Watson, seems to answer this question perfectly: “It is hoped that art, whatever it is, might still offer its small glimmer of hope and transcendence even in the age of the readymade and art as financial investment.” And: “With such great challenges mounted against subjective freedom, it cannot be the role of art to interpret the world, but, rather, to change it.”